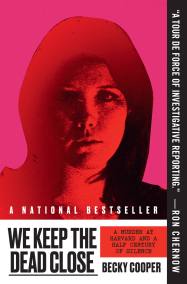

We Keep The Dead Close: Meet Jane Britton

In 1969, Jane Britton, an ambitious twenty-three-year-old Harvard graduate student was found murdered in her Cambridge, Massachusetts apartment.

Forty years later, Becky Cooper a curious undergrad, will hear the first whispers of the story that a Harvard student had had an affair with her professor, and the professor had murdered her in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology because she’d threatened to talk about the affair.

Though the rumor proves false, the story that unfolds is even more complex: a tale of gender inequality in academia, a ‘cowboy culture’ among empowered male elites, the silencing effect of institutions, and our compulsion to rewrite the stories of female victims.

The following excerpt from Becky Cooper’s upcoming true crime book, We Keep the Dead Close, describes Jane Britton’s arrival at Radcliffe in 1963.

JANE AT RADCLIFFE

That first week of freshman year, 1963, everyone in Cabot House moved as one. It wasn’t just that they all ate together. All forty-five girls, it seemed to Elisabeth Handler, were under the impression they could fit at the same round table.

At one of those group lunches, Elisabeth looked around the room. Compared with her, the other girls carried themselves like they had been groomed for Radcliffe since preschool. Julie Spring, her roommate, was the daughter of a Unitarian minister. She wore wraparound skirts and round-collared blouses. Julie’s biggest worry about coming to college was whether she could learn to shave in the shower rather than in the tub. Elisabeth wasn’t sure if she had ever been so young.

But she also felt bad for being annoyed by Julie’s enthusiasm. To be at Radcliffe really was something to celebrate. It was the most prestigious of all the women’s colleges, and, at a quarter the size of Harvard, it was the more difficult of the two to get into. “I didn’t want to be the one bad apple in the bunch, where everybody else has this wonderful experience, and then this little grump in the corner is bitter about an education most people would kill for,” Elisabeth would later remember.

Just then another first-year came bounding into the dining hall. “I did it!” she announced to the room. “I got into a graduate seminar!”

Elisabeth didn’t even know what a graduate seminar was. How did an eighteen-year-old manage to weasel her way into—

“I need to do that!” Julie gasped. Elisabeth tried not to roll her eyes.

“OH FUCK,” a voice said, across the table.

Elisabeth looked up. The girl was striking. Her eyes were green and widely spaced. Her skin was a pale ivory. Her hair was so black it was almost blue.

———

Jane was “a kick in the pants,” Elisabeth remembered. “She was sort of like a combination of Groucho Marx and Dorothy Parker. Just without the mustache.” Jane wasn’t conventionally beautiful—she liked to say she was built like a brick shithouse—but she was magnetic. She smoked and eschewed hair-sprayed updos. She had a low voice and a deep laugh that erupted spontaneously, and when she was being particularly wicked, she would cock her thin eyebrows like a bow ready to spring. Jane’s room, it turned out, was right down the hall from Elisabeth’s, and the two quickly became inseparable.

Life in Cabot took some getting used to for both of them. First there were the spartan rooms with two wooden dressers, two small desks with a wooden chair each, and bunk beds. Jane slept on the lower bunk. There were no lamps, no curtains, no rugs. Jane’s room, at least, had a window that looked out onto the quad.

The girls shared a communal bathroom, and each floor came with its own ironing board and iron. In the basement, there were laundry machines (twenty-five cents per load) and hair dryers (ten cents per fifteen minutes). Telephones were shared one for every twenty-five, but the incoming calls were routed through the student on bell desk duty, which meant their social lives were on display. Everyone could tell how popular a girl was by the thickness of her stack of pink slips of missed calls. The sign-out books—in which girls wrote where they were headed and with whom—were open for all to see.

Then there were the rules. Radcliffe distributed a handbook that the girls were expected to memorize. They were required to do five hours a week of housework: bell duty, waiting on the cafeteria tables, and light pantry work. The handbook asked that students “be discreet when sunbathing” and specified that “good taste demands that discretion shall be shown in displays of affection on Radcliffe property and in all public places.” Smoking was allowed everywhere (except in bed), but alcohol was forbidden. Occasional exceptions were made for sherry.

And there were the social rules: as freshmen, they were allowed to sign out until 11:15 any night and were allotted thirty 1 a.m. sign outs per semester. But men weren’t allowed except during parietal hours, the time when members of the opposite sex could be in the dorm. All men needed to be signed in and out by their hostesses, and the girl was expected to shout “Man on!” to alert people in the hall.

———

Radcliffe had started as the Harvard Annex in 1879, but women had only been allowed into Harvard classes since 1943. And that milestone was less about equality than convenience: Professors resented having to give the same class twice when their Harvard classes were empty because of the war. On the ten year anniversary of joint instruction, the Crimson published an article about the Harvard instructors’ experience of teaching co-ed classes. One instructor said the women in his class wore curlers and no makeup so “it was something of a shock to see a girl in your section at a House dance and discover she actually had a face after all.” Another instructor said he liked dating Radcliffe students because “Wellesley girls are prettier, but that Radcliffe is more convenient.” Elliott Perkins, a history lecturer and the master of Lowell House, was nostalgic for the old days. Though he “really [couldn’t] tell the difference intellectually,” he felt that “the Yard looked better before, with just Harvard men.”

By the time Jane and Elisabeth were freshmen, Radcliffe girls were judged side by side with Harvard students: the same classes, the same professors, the same exams. Radcliffe diplomas had started also saying Harvard on them the June before Jane arrived. Nevertheless, they felt like second-class citizens. Cliffie didn’t have access to the same scholarship money and financial aid. They weren’t allowed to enter Lamont, the undergraduate library. They were required to have escorts walk them home from extracurriculars if they were to be out past 11 p.m. There were only nine women’s bathrooms on campus, and finding somewhere to eat in the Yard to avoid trekking all the way back to the Quad between classes wasn’t much easier. A freshman boy could invite a girl to eat in the all-male Freshman Union, but it was widely known that it was tradition for the men to clink their glasses with their forks when a girl walked into the dining hall—the evident goal being to make the women as uncomfortable as possible.

When classes started a week later, Jane convinced Elisabeth to try Anthropology 1a with her. The class met three times a week at 10 a.m. and was taught by Professors William Howells and Stephen Williams. Jane and Elisabeth sat together near the back of class. They would always giggle when the same boy screeched into class late and nearly fell into his seat.

They were entranced almost immediately by the world of anthropology. “I mean, hello,” Elisabeth would later say. At Radcliffe, “I might as well have been popped out in the middle of the deepest Amazon. So this idea of ‘here we will study culture, we will pick out things that will make it interesting and different, and we will not interfere, we will blend into the background with our notebook and pith helmet and everybody will be that much wiser about the subject?’ It makes perfect sense that that’s what I gravitated to.” There was an old joke that people who went into psychiatry were unhappy with themselves. Psychologists were unhappy with society. And anthropologists were people who were unhappy with their culture.

Early that semester, one of the teaching fellows for Anthro 1a threw a party at his house and invited some members of the class. Elisabeth went, and the boy who was always late to class was there, too. Elisabeth introduced herself. She confessed that she and Jane had in fact been sticking their legs out to trip him and apologized. The boy just laughed. He said he was so tired that he didn’t realize he was stumbling over anything but his own feet.

“Peter Panchy,” the boy said.

Elisabeth and Peter kept talking and drinking the punch—red wine with cloves floating in it. By the end of the party, Elisabeth was drunk for the first time in her life. She threw up on Peter’s shoes. He didn’t mind.

Soon, Jane, Elisabeth, and Peter became a pack. They would do silly things in the back of the classroom. Sometimes Ingrid Kirsch would join them. Sometimes one or the other of them would be depressed, and Peter would bring some hideous alcohol, and they would sit out on the steps of the school across the street from the Radcliffe dorms, in the Cambridge winter, and get hammered. They bonded over the fact that they each felt alien: Elisabeth because of where she grew up; Jane because she always felt on the outside of things; and Peter because he wasn’t born into the same privilege as so many of his classmates. Peter’s father was an Albanian immigrant who had to quit Harvard halfway through because his family’s grocery store was on the verge of bankruptcy. “Just because you’ve been invited, doesn’t mean you belong,” Peter would Later remember about his time at Harvard.

———

The class of 1967 felt caught between the 1950s and ’60s. There was a mandatory abstinence lecture in Cabot House for these freshmen. The girls gathered in their nightgowns and bathrobes and PJs to listen to an older student fall apart in front of them. She told them that she had been in love with an upperclassman, had dated him for two years, had a “full sexual affair” with him, and then he left her for somebody else. Susan Talbot recalled, “She was weeping and telling us to go ahead and do our dating, but don’t lose your virginity to a man who’s going to walk out.”

In October 1963, a scandal hit. Students had been complaining about parietals, arguing that they “reinforce the idea that women are objects for sex, rather than friends or companions in love” and the only thing that they prevent is not premarital sex but “the less explicitly sexual aspects of romance: joking over breakfast, talking comfortably in the early afternoon.” The administration had had enough. Two Harvard deans pushed back, expressing deep distress over what they saw as a “loose moral situation” on campus. They vowed to make the rules governing parietal hours even stricter: “It’s our positive duty to deal with fornication just as we do with thievery, lying and cheating.”

But not even Radcliffe and Harvard could be kept in their bubble for long. In November, President Kennedy was shot. The house administrators brought a television into the Cabot common room and the girls gathered to watch. The bell of Memorial Church, which normally rang on the hour, tolled every fifteen minutes for him. It echoed eerily through campus.

———

Sophomore year, Jane and Elisabeth moved into Coggeshall, an old frame house affiliate with Cabot, a few blocks away on Walker Street. It was homey, with 1950s living room furniture, and fewer than a dozen girls. Jane and Elisabeth were much happier there—each girl had her own bedroom, they could cook in the kitchen and invite friends over—and stayed in the house until graduation. Jane was particularly fond of the head resident’s cat, Edward, a big orange fluff creature. When poor Edward had surgery to remove his balls, his testicular misfortune was an endless source of comedic delight for Jane.

Karen Black, the head resident, was struck by Jane’s charisma. Jane would “get to talking about things and you’d just sit and listen to her.” She told stories about her expeditions: the caves in Abri Pataud she’d come back from digging in the previous summer, the trains in Greece, the bazaars of Athens. They were so vivid, it felt like she resurrected the past:

Here we were, smelling like a stable, dirty, scarcely combed. Here is the Mediterranean, all plush and marble. Here are the astonished bellboys wondering whether to kick us out or not. Here is Britton, ready to do some fast talking.

“She had this terrific attachment to things of the dim past,” Karen remembered.

The divide between the class years began to feel as wide as generational gaps. Drugs hit campus that year, the Supreme Court case Griswold v. Connecticut legalized access to birth control for married couples, and the beginnings of the civil rights and antiwar movements took hold, though initial support was small. Vietnam protesters had to dodge water balloons hurled from the freshman dorms. Harvard and Radcliffe had started actively recruiting Black candidates, but numbers wouldn’t rise significant y until 1969. (In the decade prior to 1964, there were rarely more than three Black students in any of Radcliffe’s graduating classes.) Susan Talbot only became aware of the political groundswell when she lost track of one of the freshmen she was in charge of. When the young student’s friends reluctantly admitted that she was at a teach-in, Susan responded, fully serious, “I didn’t know there was a new Chinese restaurant in the Square.”

Carol Sternhell, class of ’71 and one of the first students to participate in Harvard’s co-ed housing experiment in the spring of 1970, would later remember the electricity of this moment: College is a time when you test the boundaries of your world—sex, drugs, experiences—anyway. To have the world’s mores shatter at the same time was extraordinary.

As the present day continued to encroach on Harvard, Jane became increasingly invested in the Anthropology department. She started illustrating artifacts for Professor Movius as a side gig. Almost every afternoon, after the Peabody Library closed at 5 p.m., she would go to the Hayes-Bickford, the cafeteria on Mass Avenue, with graduate students and teaching fellows for beer and coffee and gossip. They called themselves the hunter-gatherers.

Jane would relay the scuttlebutt to Elisabeth. “It was all kind of soap-opera-y and intrigue-y and it felt really political.” The way Jane talked about people in the department, it seemed like she was sleeping with everybody. “I didn’t feel like I had any grounds to say, Now, Jane, no, you shouldn’t be involved in this sort of way, this isn’t good for you,” Elisabeth recalled. Sensing a certain fragility in Jane, she didn’t even feel like she could ask how much was true, and, to be honest, she didn’t want to know.

Jane tended toward extremes in her life as well as in her stories. She was always on some fad diet—eating too many bananas or fasting for seventy-two hours one moment, and then off to the Brigham’s for a chocolate shake the next. Jane came alive at night. She worked erratically. When she focused, she blazed through her work with a vitality that had its own glow. Other times, she’d disappear into her room for days on end, only emerging for scurrying trips to the kitchen next to her room.

But those same traits—the intensity, the obstinance, the wildness—made Jane a terrific friend. She had her own gravitational pull. She may have padded herself with a wad of cynicism and pessimism but she was “a cockeyed optimist” underneath, Elisabeth remembers.

When Jane or Elisabeth got depressed or angry or sad or bored in college, they drove. Jane had access to a 1962 white convertible with red leather seats. Even in the winter, they kept the top down. They’d head to Gloucester, or to Providence, or to Revere Beach, late at night, the wind in their faces. The looming deadlines would disappear. Or when it really all got to be too much, they would treat themselves to a fancy meal at Chez Jean, a sweet French bistro on Shepard Street. At Chez Jean, “I could let my hair down with her and talk about my experiences and my past and be a little more comfortable because I sort of felt like she knew me. It wasn’t… I didn’t have to explain everything.” One such evening, there was a young couple at a table behind Elisabeth that caught Jane’s attention. The guy was loudly insisting on ordering frog legs for his date, and his date kept saying, “No, I couldn’t possibly.” Eventually, she relented. When the waiter brought the dish to the table, Jane smirked, watching the exchange happen. The girl picked up her first bite. She brought it to her lips.

Plenty loud enough for the whole restaurant to hear, Jane leaned over and let out a voluble RRRRRRIBBBITT!

Learn More:

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use