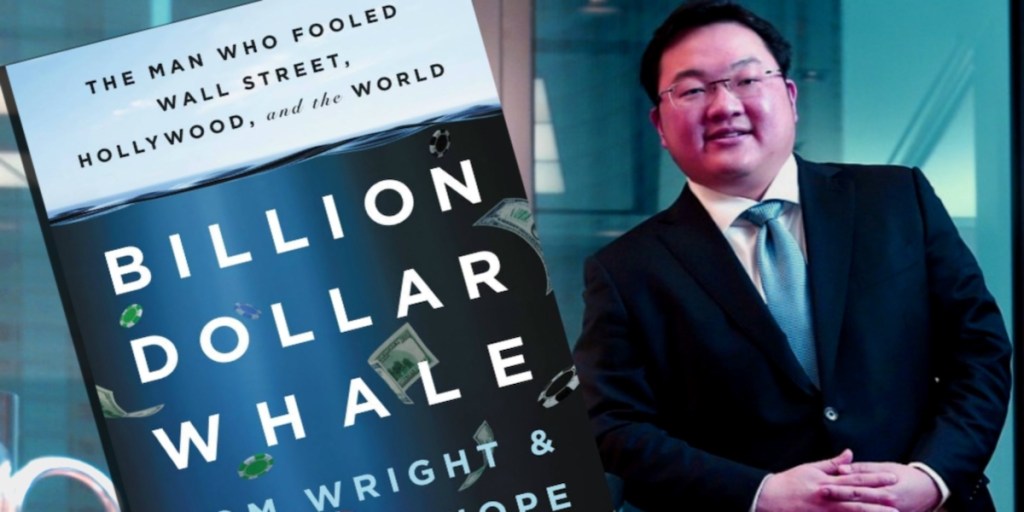

The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World

Now a #1 international bestseller, Billion Dollar Whale is “an epic tale of white-collar crime on a global scale” (Publishers Weekly), revealing how a young social climber from Malaysia pulled off one of the biggest heists in history.

Chapter 1

Fake Photos

Penang, Malaysia, Summer 1999

As he moved around the Lady Orient, a 160-foot yacht docked at a government marina on Penang island, Jho Low periodically checked he wasn’t being observed. Stashed in his pocket were a handful of photographs of his family: his father, Larry Low, a businessman who had made millions of dollars through his stake in a local garment manufacturer; his mother, Goh Gaik Ewe, a proud housewife who doted on her children; and his two elder siblings. Locating photos of the boat’s owner, a Penang-based billionaire, he eased the snapshots one by one from their frames, replacing them with those of his own family. Later, he did the same at a British colonial-era holiday home on Penang Hill, which he also had borrowed from the billionaire, a friend of Low’s family.

From Penang Hill, covered in rainforest, Low could see down to George Town, the British colonial capital named for George III, a warren of whitewashed mansions and crumbling Chinese shophouses. Beyond, the narrow straits that separated Penang island from continental Asia came into view. Situated at the mouth of the Strait of Malacca, an important sea lane linking Europe and the Middle East to China, Penang had attracted its share of adventurers, from British colonial officers to Chinese traders and other assorted carpetbaggers. The streets bustled with Penangites, mainly Chinese-Malaysians, who loved eating out at the many street-side stalls or walking along the seaside promenade.

Low’s grandfather washed up in Penang in the 1960s from China, by way of Thailand, and the family had built a small fortune. They were a wealthy clan by any standard, but Low recently had begun attending Harrow, the elite boarding school in England, where some of his classmates counted their families’ wealth in billions, not mere millions.

Larry’s shares in the garment company, which he recently had sold, were worth around $15 million—a huge sum in the Southeast Asian nation, where many people lived on $1,000 per month. But Low had begun to mix with members of the royal families of Brunei and Kuwait at Harrow, where he had arrived in 1998 for the last two years of high school. The Low home, a palm-tree-fringed modernist mansion on the north coast of Penang, was impressive and had its own central cooling system, but it was no royal palace.

In a few days, some of Low’s new school pals would be arriving. He had convinced them to spend part of their summer vacation in Malaysia, and he was eager to impress. Just as his father had raised the family’s station in Penang, earning enough to send his son to one of the world’s most expensive boarding schools, so Low harbored ambitions. He was somewhat embarrassed by the backwater of Penang, and he used the boat and holiday home to compensate. His Harrow friends were none the wiser. With his pudgy frame and glasses, Low never found it easy to attract women, so he clamored to be respected in other ways. He told his Harrow friends he was a “prince of Malaysia,” an attempt to keep up with the blue bloods around him.

In reality, the ethnic Chinese of the nation, like the Lows, were not the aristocrats, but traders who came later to the country in big waves during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The majority of Malaysia’s 30 million people were Muslim Malays, who typically treated the Chinese as newcomers, even if their families had lived in Malaysia for generations. Some of the older Chinese of Penang began to wonder about this strange kid. After Low’s Harrow friends had come and gone, the story of the photos began to circulate around the island, as did Low’s claims to an aristocratic lineage. People laughed over the sheer chutzpah. Who did this kid think he was?

In the 1960s, Penang island was a ramshackle place. The British granted independence in 1957 to its colony of Malaya—a tropical Southeast Asian territory rich in tin and palm oil—after fighting an inconclusive and sapping war against a Communist insurgency. From their jungle redoubts near the Thai border, Communist rebels bided their time, and soon would start a years-long guerilla war against the untested forces of the newly established nation of Malaysia. This lawless frontier region was an area that Meng Tak, Low’s grandfather, knew well. He’d left his native Guangdong province in China in the 1940s—a time of great upheaval due to the Second World War, Japanese occupation, and a civil war that led millions to flee the country—and settled in southern Thailand, near Malaya. He made some money as a minor investor in an iron ore mine, and married a local woman of Chinese ancestry, before moving on again to Penang in the 1960s.

The Low family lived in a modest bungalow in George Town, the capital of Penang, just a few blocks back from the peeling British-era colonnaded villas and warehouses on the palm-fringed shoreline. Many Chinese had emigrated here during colonial times to trade in commodities like tin and opium, a narcotic whose sale the British had monopolized but which now was illegal. There were dark rumors in George Town’s close-knit community about the origin of Meng Tak’s money. Some old-timers remembered him running a cookware shop in the city. But perhaps the story about iron-ore mining in Thailand was only part of the truth. Others whispered that he’d made money smuggling opium over the border.

For each version of the Low family’s history, there was an alternate recounting. Decades later, Low started telling his own story about Meng Tak, one he fabricated to explain how he was in possession of enormous wealth. The money, he told anyone who would listen, came from his grandfather’s investments in mining, liquor trading, and property. There was only one problem. Few in Malaysia—neither top bankers nor business leaders—had ever heard of this fabulously rich family. With Low’s father, Larry, the family story comes into sharper focus.

Born in Thailand in 1952, Larry Low moved as a young child to Penang and went on to study at the London School of Economics and the University of California, Los Angeles, for an MBA. On returning to Malaysia, he took over Meng Tak’s business. Despite his elite school, Larry made a disastrous investment in the 1980s in cocoa plantations that almost wiped out the family wealth. After commodity prices dropped, he used what was left to buy a minority stake in a company that produced clothes for export to the United States and Europe. This time Larry hit the jackpot.

The 1990s were anything-goes years for Malaysia’s nascent stock market. “Asian Tiger” economies like South Korea and Taiwan had taken off from the 1960s, and now it was the turn of other Asian nations. Malaysia’s economy was growing at over 5 percent annually, powered by the export of commodities like palm oil, as well as garments, computer chips, and electronic devices. Attracted by the hot growth, foreign investors poured money into Malaysian stocks and bonds. But there was no oversight. Insiders regularly broke securities laws, as if taking their cues from the excesses of 1980s figures such as Michael Milken, the U.S. junk bond king, and insider trader Ivan Boesky. Malaysians who knew how to play the system became incredibly rich, while minority shareholders lost out.

People who worked with Larry considered him charming and a wheeler-dealer, albeit with a lazy streak, preferring drinking late in nightclubs to work, but he benefited nevertheless from a run-up in the garment company’s stock. In the early 1990s, he was involved in an acquisition by MWE, the garment company in which he owned a minority stake, of a Canadian technology firm. The deal overvalued the target firm, and Larry arranged for some of the excess cash to go into an offshore bank account he controlled.

Using such accounts, often owned by anonymous shell companies set up in places like the British Virgin Islands, was common for Malaysian companies at the time. The younger Lows learned from their father about this world of secret finance, and May-Lin, Low’s sister, became a lawyer with an expertise in offshore vehicles.

When he uncovered that Larry had funneled off the money, the owner of MWE was furious and, not long after, Larry sold his stake in the company. But there was a silver lining: The increase in MWE’s stock price in the 1990s had made the Low family millionaires many times over.

Flush with cash, Larry, now in his forties, indulged his desire to party. For one celebration on a yacht, he arranged for Swedish models to fly into Penang, the kind of arrangement for which his son later would be known. The family was a big fish in a small pond—and acting the part. Larry drove around town in a Lexus, and was a member of the Penang Club, an exclusive sports club founded by the British in 1868 and whose members included well-known business families and politicians from the island. The younger Low was a keen swimmer, often doing laps on Sundays in the pool by the ocean before eating a Chinese dinner with his family.

But Larry saw all this as parochial, and he had ambitions to raise his family’s social standing. So, in 1994, when Low was thirteen, his father moved him out of the local education system to Uplands, an international school that rich Penangites chose to prepare their children for boarding school in Britain. Many elite Malaysians had gotten their education in the former colonial power, and it was still the country of choice for overseas schooling.

Larry Low opted to put down roots in England. Around this time, developers of a new gated community in London’s posh South Kensington neighborhood began to advertise in Malaysia. Some of the most powerful Malaysian politicians owned homes in the Kensington Green development, and Larry sensed it could only be beneficial for an ambitious family like the Lows to develop friendships with these people. He bought an apartment in the complex, and the family began to vacation there, which gave Low the opportunity to meet the children of Malaysia’s elite.

Larry’s alertness to status seemed to rub off on his sons, who began to forge a friendship with Riza Aziz, a college student whose family also had a place in Kensington Green. Riza’s stepfather was Defense Minister Najib Razak, who was tipped as a future prime minister. A few years older, Riza would be the key to Low’s entry into the upper echelons of Malaysia’s power structure.

Back home, in Penang, Larry ordered a beautiful cream-colored mansion built on a hill outside George Town, which with its sleek steel-and-glass look could have been plucked from the streets of Miami. The modern edifice was a step up from the somewhat modest family house that Meng Tak had constructed.

As Larry acquired the trappings of an upper-class life, the teenage Jho Low was busying himself exploring the nascent online world. Low took to spending hours at his computer, hiding behind the anonymity of the web. He began to fib in an offhand way, offering himself on an online chat site for modeling “in any part of the world.” On the forum, Low described himself as “muscular, well proportioned” but received no modeling offers. A class photo from 1994 shows Low as a slight middle-school student dressed in a white short-sleeved shirt and blue shorts, with a neat but unstylish haircut. His online activities suggested a longing to be cool. He asked people on chat rooms what hard-core techno music they suggested or which haircuts were popular in different countries.

Although he vacationed in England, Low appeared more pulled toward American culture, as was typical among younger Malaysians. One of his favorite shows was The X-Files, and he traded photos of Mulder and Scully with other fans online. Since selling out of MWE, Larry had begun to dabble in property investment and stock trading, and Low showed an interest in this world. He devoured Hollywood films like Wall Street, with its tale of insider trading and corporate raiding, and at Uplands he pooled resources with fellow students to invest in the stock market, even though he was only fifteen years old. Many adults remember Low as smooth and deferential, but adept at using this charm to get what he wanted. On occasion, he would borrow small sums of money from Larry’s friends, many of them wealthy businessmen, and then not pay them back.

Larry was plotting the next phase of the family’s rise. He had the apartment in London and the swish mansion in Penang. Low’s elder brother, Szen, had studied at Sevenoaks, a prestigious school in England. Now, he was about to send his youngest son to one of the world’s premier boarding schools. It was a decision that would catapult Low into the exclusive club of the world’s richest people.

For decades, Harrow, situated on a bucolic hill to the northwest of London, had churned out British prime ministers such as Sir Winston Churchill, but by the late 1990s it was attracting new money from Asia and the Middle East. For wealthy Malaysians, Harrow in the late 1990s had a reputation as easier to get into than Eton, another of Britain’s top boarding schools, but still an effective way to grease entry into Oxford or Cambridge and to make contacts. To reduce costs, Malaysians often would attend only the final two years of high school—to prepare for A-level exams—and that was exactly what Larry chose for his son.

In 1998, sixteen-year-old Jho Low arrived at Harrow, some of whose buildings date to the 1600s. In Penang, the Uplands uniforms consisted of short-sleeved shirts and slacks. At Harrow, pupils were required to don navy blazers and ties, topped with a cream-colored boater hat. The fees were high, more than $20,000 each year, but for the Lows it was an investment worth making.

At Harrow, Low thrived as a member of Newlands, one of the school’s twelve houses of seventy or so pupils. Newlands pupils, which had included members of the Rothschild family, the Anglo-French banking dynasty, lived in a four-story redbrick detached building from the 1800s, much like the town house of a well-to-do Victorian-era businessman. Although Low was relatively wealthy himself, he quickly fell in with a new group of friends from Middle Eastern and Asian royal families, and was struck by the cash at their disposal. These were people, including the son of the sultan of Brunei, a small oil-rich country abutting Malaysia, who were picked up by drivers in Rolls-Royce cars at the end of term.

Surrounded by his elite new friends, Low began to display a more risk-taking side to his personality. He sneaked into Harrow’s library with a group of students who had a mini roulette wheel and played for small amounts of money. On another occasion, he procured the letterhead of the Brunei Embassy from his friend and forged a letter to Chinawhite, the famous nightclub near Piccadilly Circus that in the 1990s was one of the city’s hottest spots. In the letter, supposedly from staff at the embassy, Low asked for tables to be reserved at Chinawhite for members of Brunei’s royal family. The gambit worked, and Low and his underage friends went partying alongside Premier League soccer players and models.

It was a lesson that power and prestige—or at least the appearance of it—opened all kinds of doors. Low positioned himself in the group as someone who could get things done. He’d make the bookings and collect money when it came time for the bill, making it appear like he was the one paying. He became the fixer, trading off his proximity to the truly powerful, and it had the effect of making him a focus of attention.

On vacations, Low headed to the Kensington Green apartment, where he spent more time with Riza Aziz. He knew that Malaysian politicians like Riza’s stepfather, paid only moderate official government salaries, could never afford to live in multi-million-pound homes in London’s toniest district. Everyone was aware that Malaysia’s ruling party, the United Malays National Organization, demanded kickbacks from businesses for granting everything from gambling licenses to infrastructure contracts. Many of those businesses were controlled by Chinese Malaysians, like the Lows. The situation stirred in him a moral relativism. If everyone was taking a cut, then what was the problem?

After Harrow, Low opted to attend college in the United States. He had business ambitions, and America was his choice over stuffy Oxford and Cambridge. There, on the campus of an Ivy League school, he would enter the next stage of his metamorphosis.

Chapter 2

Asian Great Gatsby

Philadelphia, November 2001

Low stood in the nightclub he’d rented for his twentieth birthday—Shampoo, one of Philadelphia’s most popular—and surveyed his domain. He’d agreed to pay around $40,000 for a full bar and canapés, and to keep out regular guests, giving the club an air of exclusivity. Only in his sophomore year, Low had spent weeks flicking through the student directory at the University of Pennsylvania. He had cold-called the social chairs of sororities to ensure the club was crammed with sought-after women. This wasn’t a normal student night of beer-pong, and everyone turned up, from the jocks to the artsy crowd and the foreign students. The bar was stocked with champagne in sufficient supply to keep everyone’s glass brimming all night.

Tipsy and swaying self-consciously to the pounding music under a gigantic disco ball, Low made awkward small talk with the women, asking them if they were enjoying the party. He seemed extremely anxious to please. At one point during the evening, a model wearing only a bikini made of lettuce leaves walked across the dance floor and reclined on a bar top. The waiting staff covered her near-naked body in sushi for the guests to eat with chopsticks. Low looked on at the spectacle, smiling as the crowd roared with laughter.

Among themselves, some partygoers that night referred to Low as the “Asian Great Gatsby,” a reflection of how their host seemed to observe his own parties, rather than partake in them. Like Jay Gatsby’s, Low’s origins were shrouded in mystery. The guests felt the need to talk to their benefactor, but conversations were stilted and trailed off. He was friendly enough but really didn’t have anything interesting to say, instead preferring to repeatedly ensure his guests were sated. Do you like the champagne? How’s the sushi? He wasn’t hitting on women in the way other male students did when they hosted parties. In fact, he wasn’t even flirting.

Low chose the univerity’s business-focused Wharton School, whose alumni included Warren Buffett and Donald Trump, for its reputation as a production line for top financiers. For $25,000 a year, students in the economics department, where Low was studying, learned the mechanics of capitalism. Many of his classmates, wealthy students from across the globe, envisioned a career on Wall Street. Low majored in finance rather than dry macroeconomics, but he wasn’t planning on a regular banking career. The Malaysian worked hard in his first year—he was a quick study with a prodigious memory—but he began to see Wharton foremost as a place to socialize and build his contacts.

That night in Shampoo—like the many others he would organize over the ensuing fifteen years in nightclubs and casinos across the world—was pure performance, orchestrated by Low to impress. For sure, he enjoyed partying, and he liked having pretty women around, but more than anything this was an investment, one that made him appear successful and indispensable. That was why, ahead of the night in Shampoo, he had made an ostentatious request: The fliers for the party should have JHO LOW emblazoned in big letters next to those of the sororities. Low handed out two types of invites, standard and VIP, promising a complimentary “premium open bar,” and with details of shuttle buses from campus to the club. He intuitively understood that people desire to feel important, part of an exclusive club, and he played on it. “Fashionable attire is a must. No jeans or sneakers,” the invites read.

Sure, Low was rich, with a family wealth in the millions. While at Wharton, he would receive regular wire transfers of tens of thousands of dollars from Larry Low to finance gambling trips to Atlantic City and to pay for partying. The money was a gift from a wealthy, doting father, ensuring Low made a name for himself with the children of influential families who attended Wharton. But even with his father’s backing, Low was stretched to afford the cost of the night at Shampoo. Unknown to his guests, he had put down only a portion of the costs up front and later stalled on paying the balance to the club’s owners, haggling for months before finally settling on a steep discount.

Low began to invite sorority members and his Asian and Middle Eastern friends to gamble, hiring stretch limos for the one-hour drive to Atlantic City. The group often gambled at the Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino, wagering a few hundred dollars a hand. Low even wrote Ivanka Trump, then a student at Wharton, inviting her to attend. Low told his friends she declined the offer on the grounds she would never set foot in one of her father’s “skeevy” casinos. The group returned to Atlantic City several times, and Low at one point was up some $200,000, but he lost all of the gains during one heady night of gambling in 2002. Those around him were shocked at the cavalier attitude he exhibited while betting the equivalent of a year’s tuition. This guy, they thought, must have money to burn.

The Malaysian worked in other ways to build his brand. He wrote articles on stocks for the Wharton Journal, the business school’s student newspaper. One of Low’s pieces, in the November 6, 2000, issue, argued Enron was no longer a conservative gas pipeline firm but a profitable financial company that had made new markets in commodities. It was only a year before Enron collapsed amid an accounting scandal, sending its top executives to jail. But it wasn’t just that the analysis was faulty; many bankers had fallen for Enron’s lies. Low had plagiarized entire sections of his piece, word for word, from a Salomon Smith Barney report. He wrote many more such pieces, copying most of them from analyst reports on Wall Street. Somehow this got past editors at the paper, and Low began to develop a reputation as a stock picker, despite being only a freshman with zero experience analyzing companies.

He began to foster an aura of a rich prodigy. On campus, he drove around in a maroon-red SC-430 Lexus convertible, which he had leased but passed off as his own. He deliberately didn’t correct rumors that he was a “prince of Malaysia,” a claim that made the other Malaysian students laugh when they heard it. Low was playing a part—and it was not just to overcome any insecurity about his provincial background, but was aimed at getting him into the right social circle. He identified the wealthiest students and pursued friendships with them. He got to know Hamad Al Wazzan, the son of a Kuwaiti construction and energy magnate, and he befriended students from the rich Gulf states of the Middle East.

In 2009, a chubby, mild-mannered graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business named Jho Low set in motion a fraud of unprecedented gall and magnitude–one that would come to symbolize the next great threat to the global financial system. Over a decade, Low, with the aid of Goldman Sachs and others, siphoned billions of dollars from an investment fund–right under the nose of global financial industry watchdogs. Low used the money to finance elections, purchase luxury real estate, throw champagne-drenched parties, and even to finance Hollywood films like The Wolf of Wall Street.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use