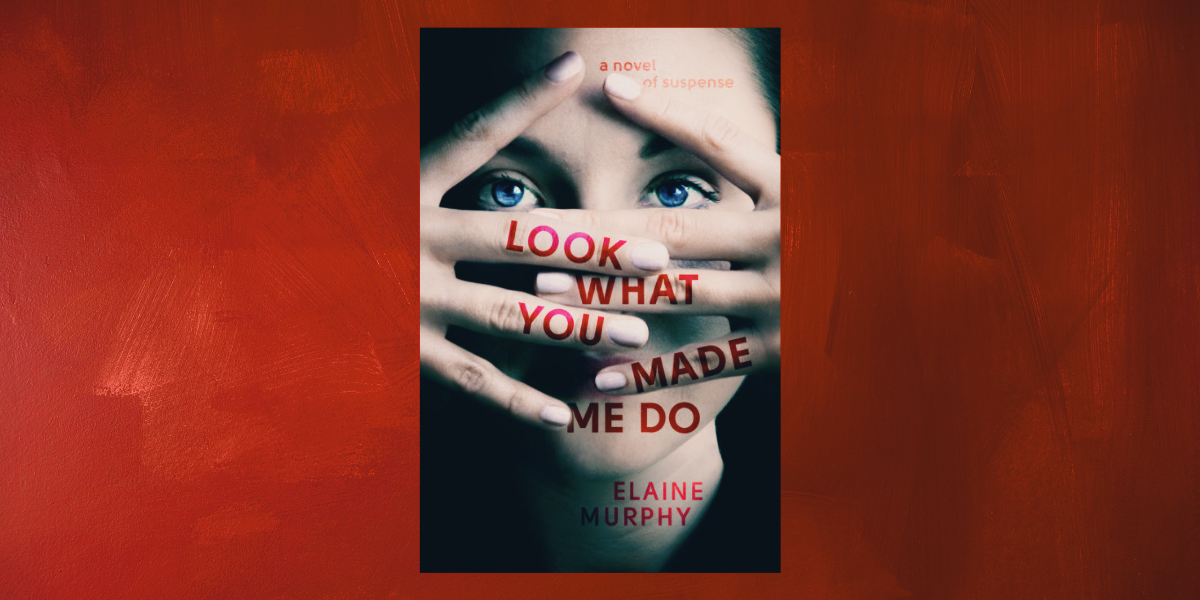

Read the Excerpt: Look What You Made Me Do by Elaine Murphy

CHAPTER 1

I’ve been expecting the call, but when my phone rings, the sound is still too sharp, more alarm than alert. The personalized ringtone grinds the world to a halt, turning my knees to gel and my stomach to mush. I should be safe in the produce section of a grocery store, but I’ve never been safe anywhere. The sound trills from my pocket, the coat vibrating against my hip, and like any awful thing, it

feels like a shock, an offense. An unfairness.

Another ring and I look around guiltily, a lemon clutched in my left hand, but the other shoppers ignore me, preoccupied with getting their groceries and getting home, away from the October cold. I consider letting the call go to voicemail, but I know she’ll just call back. She’s been getting antsy lately, and after a decade of experience, I know the signs. There’s no way to escape it. To escape her. There never has been.

I pull the phone from my pocket to see Becca’s name transposed over a picture we took three years ago. She’s standing in front of a mailbox painted to resemble a cartoon castle, with brightly colored turrets and arched windows. Her arms are folded like a sentry, eyes glaring, daring anyone to approach. As soon as the camera clicked, she’d doubled over laughing, like any goofy, fun older sister. The one I’d always wanted.

I answer the call, losing sight of the picture. “Hey.” “It’s me,” she says. “I need help. I’m moving furniture.”

I knew what she was going to say, of course, but my knees weaken further, like they do when we go to amusement parks and she insists I get on the roller coaster even though she knows I hate roller coasters. You’re thirty, Carrie, she says. Suck it up. Little kids are doing it—what’s your problem? You can’t be afraid of everything.

I’m twenty-eight, I correct her every time. You’re thirty. But every time, I get on the roller coaster. And my head spins and my stomach lurches and I feel sick and hot for the rest of the day, and the trip to the amusement park ends as they all do—with Becca being amused.

I want to say no now, too. I want to tell her it’s my one-year anniversary dinner with Graham and I’m making dinner, but I don’t. I don’t tell her because she already knows, which is probably why she picked this date to “move furniture,” and we both know I’ll cancel my plans. It’s not like I have a choice.

“I’m at the grocery store,” I say, for the sake of it, staring at the lemon in my hand.

“So?”

“So it’s my anniversary. I’m making—”

“Don’t say lemon spaghetti,” she snaps. Even when Becca needs you, she can’t be nice, not really. It’s not in her genetic makeup to be kind. We share 50 percent of our DNA, but we could be complete strangers for how unalike we are. She’s blond; I’m brunette. She has blue eyes; mine are brown. She’s a murderer; I’m not.

“It’s Graham’s favorite.” I’m not actually the biggest fan of lemon spaghetti either, but Graham is pretty much perfect apart from this one thing, so I can live with it. I grew up with Becca, after all. I’ve dealt with worse.

“Tell him to choose something else.” “I—”

“And choose another night, too,” she says. “I need help.

Moving—”

“Furniture,” I say. “I know.”

“Kilduff Park. West entrance. Hurry up.”

She disconnects before I can say anything else, and I stand in the produce section and stare between the phone and the basket in my hand, as though weighing my options. As though I have options.

I text Graham a lame apology. Work emergency. So sorry. It’s a believable lie. He knows what my job is like because we met at work. Weston Stationery is a small, business-casual office at the edge of an industrial park,

and while a job designing and marketing novelty office supplies might not sound exciting, I like it. Right now I’m even up for a promotion, which is exciting. It’s down to me and another girl named Angelica, though she’s not at all angelic. Which, in our office, mostly means she puts her recyclables in the trash and takes too long to sign birthday cards and got a tattoo on her ankle of a polka-dot binder clip to suck up to our boss. When I talk to Graham about the promotion, he tells me I have it in the bag because I’m the best person for the job. When I talk about it to Becca, she yawns.

Graham replies to my text right away. He’s disappointed, but of course he understands. He’ll order take-out. Come over later?

I’ll try.

I won’t try. Not after this. I can’t.

I empty my basket, reluctantly returning my fresh pasta to the deli counter and the French loaf to the bakery, exchanging the warmth of the store and my boyfriend for a dark park four days before Halloween to help my sister move furniture.

—–

The first time Becca killed somebody, she was seventeen. I was fifteen, a sophomore in high school, and only vaguely aware of a cheerleader named Missy Vanscheer. Missy and Becca were on the cheerleading team together

but didn’t get along so I only heard Missy’s name when it was followed by something like “skank” or “bee-otch.” I thought nothing of it when I heard whispers that Missy was missing. First, she skipped cheer practice, and the next day she wasn’t at school. Then her parents reported her missing, and that’s when it became real.

That’s also when the rumor started that Missy was pregnant, and the father was an older man and they’d run away together. Her friends swore she’d never mentioned a boyfriend, certainly not an older guy, and nobody knew she was pregnant. But the rumor persisted, and though the police investigated, they never found any mentions of a boyfriend in her social media pages, herphone, orherdiary.

They never found Missy either.

It was two years later, the day after my high school graduation and a week before my eighteenth birthday, that I learned the truth. Becca called me, panicked and near tears, totally out of character for my sister. When people described Becca, they used terms like beautiful, aloof, and manipulative. Hearing her say she needed me eroded a lifetime of lessons to the contrary and had me reaching for a pencil, asking her for the address.

“Don’t write it down!” she’d shrieked, as though she could see my notepad. “Don’t write it down,” she re- peated, more calmly. “Don’t use GPS. Don’t even bring your phone. Just remember it.”

It was only when I got to the abandoned hiking trail that I learned why.

Becca leaned against the hood of her car, smoking a cigarette, looking like the Queen Bee in every high school movie with her tight jeans and T-shirt, her blond hair in a high, shiny ponytail. Not even the towering trees and mountains could compete with her beauty.

I parked my dented little Volvo, the car I’d worked overtime at the diner to pay for, saving up my measly tips and depositing them at the bank on my way home. For months, I’d been collecting them in an envelope in my underwear drawer, until one day I went to get the money and all that remained was a five-dollar bill. Becca swore she hadn’t taken it, my $1,287, but I knew she had. I went to the bank and opened an account, and Becca came home from the mall with a new wardrobe. My parents knew but were too wary of her to do anything, which probably had a lot to do with how we came to be at the hiking trail.

“It’s about time.” She tossed her burning cigarette on the ground, heedless of the nearby trash can and dry leaves that littered the area.

“Um. . .” I looked around. We were alone. The air was clean and warm, scented with dirt and pine, but there was something else there, too. An undercurrent that made me more uncomfortable than normal.

“What are you wearing?” Becca groaned at my jeans and T-shirt, Cookie Monster printed on the front, gobbling a cookie.

I resisted the urge to tug at the hem of my shirt, the fabric clinging to my muffin top just a little too tightly. If I drew her attention there, she’d make a snide comment about my weight, the extra ten pounds everyone swore was baby fat until I was too old for the excuse.

“Just . . . clothes.”

She rolled her eyes. “Well, come on.”

But when I started for the mouth of the trail, ready to follow even without knowing the destination, Becca didn’t budge.

“What?” I asked, staring back at her.

She sighed, her glossy lips turning down in a pout. “We have to get something.”

I glanced around again. Apart from the ignored trash can and a wooden sign with a map of the trail dangling by a single rusty nail, there was nothing to “get.”

“Where is it?”

Her pout deepened, as though my question disappointed her, and Becca yanked open the back door of her car—my parents bought it for her as a graduation gift—to retrieve a yellow bag with a garden store logo stamped on the side. She dumped out two pairs of garden gloves printed with bright-purple flowers, still held together with the tags. While I was surprised to see the gloves, I was more surprised to see the bag. Becca didn’t normally “pay” for things. She just took what she wanted, and always got away with it. I shoplifted a pack of gum when I was twelve, got caught seconds later, and had my picture posted on the wall of shame at the front of the store for a year. My parents were very disappointed.

I accepted a pair of gloves and copied Becca, snap-ping them apart and pulling them on, though there was almost certainly no garden in the vicinity. With one more heavily exaggerated sigh, like this was the most tedious day of her whole life, Becca reached in through the open driver’s-side window and pressed a button to pop the trunk. The lid lifted slowly, and even from my position in front of the car, my heart started to pound, and nausea roiled in my gut.

I’d never seen inside Becca’s trunk before. It had never occurred to me to check; there was no reason. But in that moment, I knew I definitely did not want to know what was in there.

“Well, come on,” she said, like I was the problem. I didn’t budge. “What is it?”

“Come on.”

“What is it?” My voice rose an octave, and Becca finally looked at me, really looked at me, and a little furrow appeared between her perfectly arched brows. She opened her mouth to speak but then closed it, her cheek twitch- ing while she chewed on it. She always chewed on the inside of her cheek, was always spitting blood. Her blue eyes grew shiny with tears.

“Something bad happened,” she whispered.

My feet propelled me forward automatically, the need to help, to fix, so ingrained I didn’t even have to think about it.

“What?” I was also whispering, though there was no one around to hear. The trail had been deemed unsafe years ago after three hikers fell to their deaths, and no one came out here anymore since Brampton boasted plenty of other, less deadly, trails to enjoy.

Becca’s wet eyes flickered to the trunk, and again my feet moved, one step, then two, until I could just see the edge of the black carpet lining. I couldn’t see anything more than that, but the smell I’d noticed earlier, the one that felt out of place in the clean, bright forest, was stronger.

I inched forward and saw a foot. A human foot. In an orange-and-white canvas sneaker, laces neatly tied, a pale ankle peeking out beneath the hem of a pair of black pants.

I recognized the sneaker as Shanna’s before I recognized her face, covered in crusted blood and bruises, lips and eyes swollen shut, dark hair matted and stuck to torn flesh. She was the person in a movie who’d been hit by a bus and barely survived, so brutally damaged it was almost impossible to believe. Except the way she was folded into the space, limbs at weird, crumpled angles, her neck clearly askew, made it all too believable that my sister had a dead girl in her trunk.

More specifically, she had her dead co-worker in her trunk. I recognized Shanna because we’d gone to school together. She’d been in Becca’s class, two years ahead of me, but that hadn’t stopped her from flirting with my tenth-grade crush. I’d been obvious and awkward, and the whole school knew my feelings, though I’d have rather died than admit them. Shanna invited him to the winter dance and he happily accepted, and I wore mourning black for a week and cried myself to sleep for two. When the tires on Shanna’s car were slashed the night of the dance, I’d even gotten a visit from the police, but I’d been home with my parents and had an embarrassingly ironclad alibi. I’d endured a month of taunts of “loser” and “psycho” in the hallways until eventually the school moved onto a new teenage scandal, Shanna graduated, and I never thought of her again. Until now.

I gagged, the combination of the sight and the smell and the knowledge more than I was ever going to be ready for. I lurched toward the tree line, fingers gripping the nearest trunk for balance, and dragged in breath after breath, nose running, mind reeling, trying to understand.

I had a lot of questions, but somehow, deep inside, I knew that the most basic, essential answer was this: Becca had killed somebody.

I don’t know how much time passed before I mustered the nerve to face my sister. She’d lit another cigarette and was pacing the length of the car, lifting an irritated brow when I finally looked at her.

“Are you ready now?”

“Ready for what?”

“To help me move. . .” She gestured toward the trunk.

Toward Shanna’s broken body. “It.” “That’s Shanna!”

“Obviously,” Becca snapped, then glanced into the trunk and pursed her lips with distaste. “Anyway. Let’s go.”

“Go where?”

She jerked her chin toward the mouth of the trail, already darker and more ominous than it had been minutes earlier. “Up there.”

“Why?”

“Well, she can’t stay here, can she?” “She—but—you—I—” My stomach attempted an-

other escape through my mouth, but I swallowed it down, eyes watering at the effort. “What happened?”

Becca heaved a petulant sigh. “We had a misunderstanding.”

Though I wanted to look anywhere but, I found myself looking at the dead girl—at Shanna—again. It was al-most impossible to catalog the magnitude of her injuries, the sheer scope of the damage. And looking at Becca, tall, beautiful, and unscathed, told me she didn’t do this. At least, not with her hands.

I held her stare as I passed, walking around to the front of the car where she’d been standing so casually when I arrived, the paint gleaming in the afternoon sunlight. I glared at the shiny silver bumper and it winked back at me, like we were in on a secret. The secret being, I belatedly realized, that it was brand new because the other one had been used to kill somebody earlier that day.

“Did you—”

“Yes,” Becca said tersely. “I accidentally hit her with my car.”

My stomach lurched. “What was the misunderstanding?”

“C’mon,” she muttered, gripping Shanna’s ankles and yanking them over the lip of the trunk, things cracking and popping as the locked joints tried to straighten.

“What was the misunderstanding?” I repeated.

Becca paused, holding a dead girl’s feet, and stared me down. Tried to, anyway. When I didn’t relent, she huffed. “She said she saw me taking money from the till, and she misunderstood. Then she misunderstood how fast I was driving and stepped in front of my car.”

“You—” I’d once hit a parked car, not hard enough to leave a mark, and was shaken for days.

“Accidentally,” she added, as an afterthought. Or a reminder. “Now let’s go.”

When I still didn’t move, she scuffed her foot in the dirt and released Shanna’s ankles. They dropped against the edge of the car with an empty thud.

“Carrie,” Becca said, fingers curling into her palms, “please.” I could see her chewing on her cheek again, the inside of her bottom lip stained crimson, like she’d eaten a cherry Popsicle. She drew in a breath through her nose, nostrils flaring, and blinked rapidly, tears clinging to the ends of her lashes. “She was so horrible to me. She lied to our co-workers about me, to our boss. She knows how much I love this job, and she wanted—she wanted to destroy me.” A single fat tear rolled down her cheek, glinting in the sunlight like a diamond. “And if anyone finds out about this, they’ll think I did it on purpose, and I’ll—I’ll—” She gulped dramatically. “I could go to jail.”

Becca worked at the jewelry store at the mall, fancy enough that not everybody could afford to shop there but not so fancy that they had guards. She got minimum wage and earned commission and regularly bitched about neither being enough, though her looks helped her sell far more earrings and necklaces than the next-best sales- person. She didn’t love her job, but it paid the bills. Becca’s dream was to marry rich and spend the rest of her life sunbathing and bossing around the help. And while she’d dated plenty of wealthy men in her twenty years, none had been reckless enough to pop the question.

“Carrie?” she said softly. “Please? Let’s go, okay?” She picked up Shanna’s ankles and nodded at her battered head.

But I balked. “I’m not touching her head,” I said. I looked away from the pulpy, mottled skin, down over Shanna’s chest, covered in the white button-up shirt they wore at the store, the collar smudged with dried blood, a smear of dirt on one side. Her pants were torn at the knee on the same side but were otherwise intact. Somehow her face had sustained the brunt of the impact, managing to hit a bumper no taller than knee-high.

Becca sighed. “God. You’re so dramatic. You take her feet then, you baby.”

She shouldered me out of the way as she stuck her hands under Shanna and into her armpits, heaving her torso out of the trunk. Shanna’s neck stayed askew, her ruined face tilted sharply to the side, like she was sleeping uncomfortably.

Becca was barely perturbed. In fact, she was more irritated by my reluctance than Shanna’s dead-ness. She gave me the imperious look she’d given me a million times in my life, and even though my throat tightened and my gag reflex was on high alert, I felt my fingers wrapping around Shanna’s shins, careful to touch only the fabric, not her skin, and lift.

She was stiff. Her limbs remained bent and twisted, but she didn’t droop or sag, and even through the fabric, I could feel how cold she was. How not-recently-dead she was.

“When did this happen?” I asked, already breathing hard as we trudged toward the mouth of the trail. What we were going to do if we happened upon a stray hiker, I didn’t know.

“When I called you,” Becca said. I watched her face, but it remained neutral. If anything, she looked merely determined, and we shifted so we walked on opposite sides of the overgrown path, shuffling our feet in time.

“Half an hour ago?” “About that.” “Where—”

“Jesus, Carrie. I don’t want to relive it.” She said it as though she were the one having the worst afternoon of her life.

“Well, aren’t people going to wonder—” I began, stop- ping when she gave me a warning look. There wasn’t a soul in town who didn’t know that look. I’m pretty sure birds have fallen out of the sky after that look.

“Of course they’re going to wonder,” she said, like she was speaking to a toddler. “And they’ll just have to wonder because they’re never going to find her, are they?”

“I don’t—” I stumbled over an exposed root, its gnarled fingers looking too much like a hand crawling out of the dirt. “I don’t know. Where are we going?”

“Not far. You didn’t bring your phone, did you?” “No. Did you?”

“Of course not. Have you ever seen a movie? The police trace your phone, and then you get caught.”

“You thought about that?”

She cocked her head, eyeing me patiently. “I thought about you,” she said, with emphasis. “That’s why I told you not to bring your phone. To help you.”

I might have been weak enough to help Becca, but I wasn’t stupid enough to believe her. Or argue with her. “Okay.”

She either bought the lie or decided to accept it, and we walked the next fifteen minutes in silence, our footsteps and my gasping breaths the only sounds as we made the steep climb. I was sweating profusely when we finally stopped at an indiscernible spot on the path, lined by trees on both sides.

“That way,” Becca said, nodding toward the trees at my back.

I glanced over my shoulder. “Where?”

“Just go in. Maybe ten, twenty feet. Watch your step.” She didn’t give me a choice, just nudged me with

Shanna’s stiff body, my sweaty left hand slipping in its glove and sliding up to her knee, hard as a rock beneath my palm. I gagged and recoiled, nearly dropping her corpse, muttering to myself as I regained my footing and backed warily into the woods. It was much cooler in there, and even quieter than the trail, nature absorbing our sounds, obscuring our sins.

“Just a little farther,” Becca said. “Keep an eye out.” “For what?”

I yelped as the forest abruptly ended and a sheer cliff began. There was no warning. Just a wall of trees, slightly thinner than the rest, and then blue sky and the wide, terrifying expanse of the gully below.

“That.”

Unceremoniously, Becca dropped Shanna, who crashed onto the pine-needle carpet, and I squawked and dropped her, too, debris scattering over my shoes. Even through the garden gloves, my hands left sweaty prints on her pants, and as I bent over and heaved for breath or mercy or anything, sweat dripped off my forehead and onto her leg.

“How did—how did you know this was here?”

Becca shifted, and I backed away instinctively, two steps from the cliff, one arm wrapping around a tree. Her mouth quirked, and she gazed out over the emptiness, her toes right at the edge as she peered down. From my position, I guessed it was about a hundred yards to the bottom, and it didn’t take much to assume that was where Shanna was going. It would explain her battered face far better than Becca’s hit-and-run “misunderstanding.”

Becca shrugged. “I just do. Any last words for Shanna?” I faltered. “Ah, I—”

She laughed. “Just kidding. Bye, bitch.” Then she crouched down and hoisted Shanna’s body over the edge.

Just like that. One second alive, one second dead, one second gone.

I knew I shouldn’t, but I dropped to my knees and watched, seeing something white bounce off the ridge of the cliff, spiraling into the green growth below, then disappearing from sight.

Slowly, I raised my eyes to Becca’s.

She gazed down at me, her expression open, expectant. “You shouldn’t have sweated all over her,” she said.

I blinked. “What?”

She pulled off her gardening gloves and shook them out, looking for all the world as though she’d just finished pruning a rosebush. She didn’t have a drop of sweat or dirt on her.

“You shouldn’t have sweated so much,” she repeated. “I gave you gloves so you wouldn’t leave DNA behind, but you just sweated all over her. You’d better hope they never find her body.”

My jaw dropped, like a door easing open, reality easing in. “DNA—” I began, then closed my mouth. I’d been thinking about Becca and Shanna, but nowhere in the scenario had I thought about myself. “But you—your DNA—”

Becca shrugged. “Yeah, but we worked together. I lent her my shirt. It would make sense for my DNA to be on her. But you? You didn’t even know her.”

“They can’t—”

“You probably got hair on her, too. You’re always shed- ding like a dog. And if they ask people about who had issues with her, someone’s going to remember how you practically stalked her in high school because she dated that loser you liked, then you slashed her tires.”

I pulled myself to my feet, sparing half a second to fret over my frizzy brown curls. “I didn’t slash—”

“Don’t worry, Carrie. I would never tell on you.” “You’re the one who—”

“And even if they do find her body—if they trace it back to the day she went missing, and if somebody did suspect you, or if you did get arrested, I mean, technically you’re seventeen, right? A minor?”

Her voice rose slightly at the end of each sentence, but they weren’t questions. They weren’t things occurring to her on the spur of the moment. Just like she hadn’t called me immediately after she killed Shanna. Or replaced her bumper. Or bought the gloves. I was her fall guy. Her sister.

“Anyway,” Becca said brightly, “we’d better get back before it gets dark out. Who knows what’s hiding in the woods?”

I was trembling so violently I could barely walk, my teeth chattering, skin clammy. All the sweat had dried, leaving my skin crusty and itchy and somehow cold. Like the realization that my sister was a murderer wasn’t enough, but she had implicated me in it, too. For no reason other than the fact that she could. She had chosen to beckon me into her twisted web, and I had been foolish enough to come.

She sighed sympathetically when we found the trail and reached out to tuck my hair behind my cheek. “C’mon, Carrie. Don’t be weird. It happened, and now it’s over. Mom and Dad will never know. We’re family, and we always have each other’s backs.”

But reality was setting in too quickly, and the fact that my whole life had just changed was more than my brain was willing or able to handle. My sister was a murderer. And I was an accomplice. I could still go to the police. I could tell them everything. They could probably find the car wash and the body shop where she had the bumper fixed, maybe get video of Becca buying the garden gloves.

But they could also ask people about my history with Shanna, the classmates who’d called me a psycho, and review the records from the interview when I’d been questioned about slashing her tires, a mystery that had gone unsolved until just now. If history tells me anything, it’s that Becca will win this war, the way she wins everything else.

“Carrie?” Becca prompted, tipping up my chin with the side of her finger. “Don’t panic. It’ll be all right. They won’t find her. I promise.”

“How—how do you—you know?” I stammered. “Because they never found Missy,” she said simply.

“And Shanna was skimming from the register and probably took off for Mexico. So there’s no reason for anyone to search, is there?”

It was a force of will to meet her eye and shake my head, the gesture leaden and complicit.

Becca beamed at me. “You’re the best, Carrie. I knew I could trust you. And you can always trust me, too. Now let’s go get something to eat. All this fresh air has made me hungry.”

—–

Kilduff Park is the largest green space in the town of Brampton, Maine, with nearly two square miles of flat, forested land. There are areas designated for visitors, parks and playgrounds, and trails and lakes, but for the most part it’s wild, sprawling forest. In the summer, it bustles with tourists and locals, everyone coming out to enjoy afternoon picnics and sunbathing. But tonight, Friday, October 27, at shortly after six, it’s pitch black and a cold wind snaps through the trees, rattling bare branches like a menace.

I can see Becca’s car in the corner of the lot. It’s a black sedan with a rabbit’s foot hanging from the rear-view mirror, and she’s had it for ten months. Because of her hobby, she trades in her cars almost yearly, always choosing something bland and generic and distinctly forgettable. I once asked where she took the cars she traded in, the ones with smashed front ends and blood and bone buried in the cracks, but Becca just gave me a look. Psychos like Becca have friends in low places. I don’t know what she does to repay them, and I imagine that’s best for everyone.

The car looks lonely with the engine off, the windows already beginning to frost. Becca must have gotten a head start. I park a few spaces down, leaving the car idling as I zip my coat and yank on a wool hat, mustering up my nerve. It’s been ten years since we carried Shanna’s body into the woods, ten years since anybody’s seen a trace of her. And since then I have helped Becca hide eleven bodies, all of whom had a misunderstanding with the front of her car.

Tonight is lucky thirteen.

I shiver again, and not just from the cold. Taped to the lamppost, framed neatly by my headlights, is a hand- made poster about a missing girl named Fiona McBride. I’ve seen the signs around town for the past week, an uncomfortable itch starting between my shoulder blades and quickly spreading. I’ve read the posters, memorized them. Seventeen years old, red hair, blue eyes, average height and build. Last seen wearing a pink hoodie and jeans.

Odds are good I know whose body I’ll be burying tonight.

With the exception of Shanna, I haven’t known any of Becca’s victims. Sometimes because they’re random strangers, sometimes because a meeting with Becca’s bumper batters their face so far beyond recognition that not even their family would be able to identify them.

I force myself out of the car, wincing at the brittle cold. Almost instantly, the tip of my nose is numb, and my eyes are watering, tears freezing at the corners. I hunch into my coat and yank my hat down farther over my ears, following the narrow footpath that leads into the trees. This isn’t one of the main trails that wind through the forest, past pretty points of interest. This lightly worn strip of grass is the route people take when they want to avoid those points of interest. The ones who venture this way are selling drugs or sex, people I’d generally steer clear of. But entering the woods and worrying I might stumble across a drug deal is like jumping into a polar bear pen at the zoo and worrying the water will be cold. I know there are worse things out here.

And she’s waiting for me.

I keep my head ducked as I hustle toward the tree line about twenty yards away. In the fading light from the parking lot lamps, I can see flattened strands of grass where something heavy has been dragged into the woods, like prey being pulled into the predator’s lair. I shudder, picturing the girl from the poster. Most of the time I don’t know who Becca has killed, and I don’t ask. It’s different when you can put a name to the pale, blank face.

“It’s about time.”

I nearly jump out of my skin when Becca speaks. She lurks just inside the deepest shadows, her black coat, jeans, and hat making her nearly invisible. All of a sudden, it feels like the modicum of safety provided by the lights from the parking lot is gone, leaving the world a nasty cocoon of Becca’s making.

“I came as fast as I could.” “Well, I’m freezing. Let’s go.”

Even now, a decade later, Becca is the same blond, beautiful psychopath she always was. She crouches in front of a rolled-up carpet and wraps her hands around the end. Since Shanna, she’s refined her body disposal methods, and this rug is her favorite choice. She keeps it in her trunk for such occasions, transferring it from vehicle to vehicle as she trades in her cars. Never before has a six-by-eight-foot piece of wool and cotton been so ominous; I can’t see the floral pattern without wanting to gag. Becca thinks it’s funny.

Unlike my first time, I don’t dawdle. I don’t protest or ask questions. I just scoop up my end—the feet, always the feet, now—and straighten. Becca walks quickly, our routine well established. She leads; I follow. She kills; I don’t. She feels no remorse; I do. But Becca doesn’t care about my feelings, because she doesn’t care about anybody. She made that clear the few times I tried to protest or tell her I couldn’t move a body. All they have to do is find Shanna, she’d remind me. Or maybe they don’t have to look for Shanna after all. What if somebody else went missing? What she was really asking was, What if that somebody was Graham? She knows where he works. Where he lives. It was my boyfriend Alister before Graham, and Jackson before him. It was my occasional friend, my neighbors, anybody I dared care about. So I help move nameless strangers instead of my friends.

The body is light, and the rug is wrapped tightly, molding easily to the slim figure inside. I can feel stiff legs beneath my hands, make out the bump of an ankle bone. The body is female. I don’t think Becca has ever killed anyone this young before, but I can’t rule it out completely. I only know about the bodies she asks me to help hide.

Becca moves through the trees like a panther, navigating her way in the dark with ease. I follow because I have no choice, the white puffs of her breath like unwelcome smoke signals in the night. We don’t hide bodies in the same places. I’m not sure how Becca chooses her sites, and I don’t care. I don’t want to know. I don’t want to be more complicit than I am, if that’s even possible at this point.

Right now I know the location of thirteen bodies, have the solution to thirteen families’ heartbreak. Answers to the questions that will haunt them until they die. And I say nothing. Not even a whisper. I wouldn’t dare.

After we hid Shanna, Becca started leaving something behind with each body to tie me to the death. Maybe a tissue or a few strands of hair; once she told me she put my phone number in somebody’s pocket. I can’t implicate Becca without implicating myself, and I’m still too selfish to take those last steps.

I wonder how she met Fiona. What Fiona did to make her angry. Sometimes she talks while we hide the bodies, telling me why she did what she did. They cut her off in traffic. Made a rude comment when passing her on the sidewalk. Talked too loudly at the movies. It’s impossible to predict what’s going to set Becca off, and it’s pointless. The only guarantee is that it’s inevitable.

“All right,” she says eventually. “This is the spot.”

I shiver and glance around. We’ve entered a small pocket in the forest, no more than fifteen feet in diameter, the ground flat and covered with fallen leaves that crunch noisily underfoot. A dense wall of trees surrounds us, their bare branches cracking against one another in the icy wind. The full moon glows overhead like a ghostly spotlight.

I shiver again, and this time Becca smirks. “Scared?” she asks.

“No,” I lie. I’m in a dark forest with a dead body and a serial killer a week before Halloween. Of course I’m scared. I’m not the crazy one.

“Here. Let’s dig. You’re lucky it hasn’t gotten too cold yet; the ground’s not that hard.” She drops her end of the carpet, the body making a sickening thud as the head smacks the ground, and strides the short distance to the tree where she’s propped the two shovels she must have brought in earlier.

My teeth are chattering, and my nose is running. I need to get a tissue, but my hands are still full so I crouch to set down the carpet as gently as I can. The rug unfurls slightly, exposing a pale foot, its toenails painted in dark polish, the color stark against the glowing white skin. Shadows from the clacking branches flicker over her flesh, and that’s when I spot it. Right there, on her ankle, a tiny dark shape, a square with a set of wings. I recognize it from the office. A binder clip.

It looks black right now, but in the fluorescent light of Weston Stationery, it’s bright red with tiny white polka dots. Angelica boasted nonstop about her tattoo, as though it proved her dedication to the company and erased her negligible sales stats. I’d remarked on this to Becca after a bottle of wine and a particularly teary episode of The Bachelor. I told her about Angelica, how she was kissing up to our boss, trying to steal the promotion for which I’d worked so hard.

I don’t always know how Becca picks her victims, but in this case I do know. I picked her.

“Are you going to admire her or bury her?” Becca asks, jamming the shovel into the dirt near my foot like a stake.

“You killed Angelica?” I can’t take my eyes off the rest of the carpet, like it’ll unroll itself and Angelica will jump out and shout Surprise! and this will all be a terrible, morbid joke. Because I know better than to do this. To talk to Becca. To tell her anything I like, anything I dislike. Anything she can use against me.

“That’s her name!” Becca exclaims, like I’ve solved the real mystery. “Man, that was driving me nuts. Angela? Angelina? Angelica. Right. Angelica.” She drops the shovel so it topples over and bangs off my shoulder, then my skull, but I’m too numb to feel it. “Let’s bury Angelica . . . right. . . here.”

She chooses a spot near the edge of the circle, where the gnarled tree roots disturb the earth and our fresh grave won’t be as noticeable to anyone foolish or crazy enough to venture this deep into the woods, where serial killers and their sisters wait.

I use the shovel as a cane, propping myself up as I stand, my knees weak. “I know her,” I say inanely.

“Knew her.” Becca’s busy testing the dirt with the tip of her shovel, as though if we dig a hole that’s an inch away from perfect, something bad will happen. Something worse.

“Becca!” My voice is sharp, and Becca finally looks at me, her bland, beautiful face a porcelain mask in the moonlight.

“What?”

“I know her! People know I know her! Knew her,” I correct, before Becca can interject. “And we’re up for the same promotion! Don’t you think people will suspect me? The police will talk to me?”

“Um. . .” She finds a spot in the earth she likes and digs in with her shovel, using her foot to drive it in extra hard. She’s had a lot of practice. “Maybe? But you have an alibi, right? Weren’t you at hot yoga or the gym or . . .” She studies me doubtfully, as though she can see my muffin top through my parka. “Something?”

My heart, rattling like a runaway train in my chest, slows by half a second. I do have an alibi. I was at work, then hot yoga, then the grocery store. I saw Angelica at the office this morning so Becca killed her at some point when people—and cameras—can prove I was somewhere else, not murdering anyone.

“But I knew her,” I say. “I can’t—I can’t bury—” Becca’s brow furrows. “You can,” she says. “You’re al-

ready here, and you have a shovel.” She sounds perplexed, like she truly can’t relate to my feelings. She does this sometimes. All the time, actually. She’s a psychopath, incapable of feeling things the way other people do, unable to register the emotional significance of language or action or literally anything, but she recognizes it. She studies it. She manipulates it, the way a sculptor shapes clay, molding it into whatever she wants.

There’s no point in arguing with Becca. Not just because she’s likely to kill you, but because if she doesn’t win in that moment, she’ll circle back when you’re least expecting and bring it up. Again. And again. And again. Until she wears you down. Until you’re so tired you just give in. And the next time you argue, and the time after, you remember the last time, and then you just don’t bother. Becca’s focus is singular, and being in Becca’s sight line is the worst thing that can happen to a person because she never gets tired and she always gets revenge.

I picture Angelica, her slim figure just a few inches over five feet, and position myself the appropriate distance from Becca to start digging the opposite end of the grave. She was wrong; the ground is hard. There are rocks and roots, and even through my gloves, I can almost immediately feel blisters forming. I’m sweating within minutes, damp curls poking out of my hat and sticking to my cheeks.

“You know,” Becca says after ten minutes of silent, sweaty digging, “I’ve been thinking.”

That can’t be good. “Oh?”

“I need a trademark. A calling card.”

I use the back of my gloved hand to wipe sweat out of my eyes. “What?”

She grins. “A calling card. For the bodies.” “Why? They’re never found.”

“Yeah, but if they are. Like, what if, twenty years from now, they find three of the bodies? If there’s no calling card, it’s just, like, three dumb bodies. But if I have a signature, they’re mine.”

“Why would you want people to know they were related?”

She stomps her foot. “Would you stop trying to ruin this?”

“I’m not.”

“Anyway. I know what I’m going to do.”

I don’t encourage her, but she uses her teeth to tug off her glove and reaches into her pocket for something small and cylindrical.

I squint in the dim light. “Is that lipstick?”

She grins. “Yep. I’m going to put it on and kiss their foreheads. If they still have foreheads. Or somewhere. I’ll kiss somewhere. Like the kiss of death. Isn’t that amazing?”

Obviously it’s not amazing, just like it’s obvious that telling Becca as much would be a wasted effort.

“It’s gross,” I say instead. “Kissing a dead body.”

She shrugs and applies a generous coat of lipstick. “No worse than kissing Graham.”

I don’t rise to the bait, ignoring her as I fish a tissue from my pocket and wipe my nose. When I lift my head, I spot movement in the wall of trees behind Becca. It’s fast and slight, one shadow shifting among others, two pale white dots blinking, gone just as quickly as they’d appeared. I stiffen and squeak, and Becca pauses in her makeup application.

“What?”

My eyes are locked on the forest behind her, now dark and still. “There was someone there,” I say.

She glances over her shoulder. “Where?” “In the woods. Someone watching.”

She snorts and puts away the lipstick. “Really, Carrie?” “Really, Becca.”

Becca turns to the trees and gives a pageant-like wave. “Hello!” she calls. “My name is Becca Lawrence, I’m a Virgo, I enjoy short drives at high speeds, and my greatest dream is to eradicate hunger in the whole world!”

“Would you shut up?”

The woods around us, previously dark and dead, now feel alive and watchful. Whoever—whatever—it was could still be there, just out of sight in the shadows. Or they could have circled around, using Becca’s voice as cover, approaching from—

I yelp at a loud crash behind me and race into the center of the clearing, gaping at the spot where I’d just stood. Becca is still in the same place, doubled over laughing.

“Your face!” she exclaims, and I see a glint of moonlight on scuffed metal where her shovel lies. She’d tossed it behind me to scare the shit out of me. And it had worked.

“That wasn’t funny,” I snap, stalking back. “Let’s just get out of here.”

“Hang on, hang on,” she says, lifting a hand as she crouches next to the rolled carpet. “Gotta give Angie the kiss of death.”

“Angelica,” I correct her.

“Of course,” she says, peeling back the carpet so Angelica’s body lies exposed and still. “My apologies, Angelica.” Where in life Angelica was what an older male co-worker called a “demon spitfire,” she is indeed angelic in death. Small and pale, with skin that glows in the moonlight. Her face is not damaged; it looks like she’s only asleep. The front of her white blouse is stained dark with blood and dirt, and her skirt is bunched halfway up her thighs, showing scraped knees and smears of dried blood on her calves. Her shoulder-length dark hair is splayed around her head like a fan, and Becca uses her thumb to

push a strand off her forehead.

“Ooh,” she says. “Chilly.” Then she gives a maniacal laugh that only makes this entire, dreadful situation im- possibly more dreadful and leans down to press her lips to Angelica’s cold forehead. She lingers too long, knowing it makes me sick. She’s already messed with Angelica; I’m the only one left for her to amuse herself with.

At least, I’m supposed to be. My eyes skitter around the tree line, but there’s nothing there. Not that I can see, anyway. The wind picks up, rattling the branches and the leaves, making my skin feel brittle and cold. Becca’s waiting for me to beg her to stop touching the body so we can go, but I won’t give her the satisfaction. I dig another tissue out of my pocket and wipe my nose. I don’t need Becca to leave clues on the bodies; my DNA is probably everywhere. The only consolation is that if I go to jail, Becca will go, too, and Brampton will finally be serial-killer-free.

“Fine, fine,” Becca says, shoving herself up from the cold ground and rolling her eyes at my non-drama. “All done.” She grabs an edge of the carpet and flips Angelica’s stiff form into the grave, the body landing with a muted thunk. I didn’t like Angelica in life but I feel bad for her in death, though I know Becca will mock me and do her best to make things worse if I let on that I care. Becca can always find a way to make things worse.

I grab my shovel and start scooping dirt back over the body, ankles disappearing, then shins, then knees. Becca does the same on the other end, obscuring the dark lipstick mark on Angelica’s forehead. It takes far less time to fill in the hole than to dig it, and maybe it’s because the work is easier or maybe it’s because I can’t stop the anxious spiders crawling up my spine, telling me someone—or something—is watching from the woods, but I can’t get warm. I’m cold, my fingers numb, thighs aching. My eyes keep darting into the trees, searching for something I don’t want to find.

“Calm down, Carrie,” Becca says, catching me. “There’s no one out there. What kind of lunatic would be in the woods right now?” Her lips quirk at her own joke, but I roll my eyes, refusing to smile.

She pats the earth loosely over the grave, and we use fallen leaves and branches to cover it so it doesn’t look freshly disturbed. By the time we’re done, it’s like Angelica was never here.

Becca rolls up the shovels in the carpet and tucks the bundle under her arm. “You know what we should do right now?” she asks, leading the way out of the clearing toward the spot where our unseen watcher may or may not have stood.

“Go home, take a shower and a Valium?” She laughs. “You’re so funny, Carrie.”

I wasn’t joking, but I don’t correct her.

“We should go to the biodome,” she continues. “They have that promotion right now where you get special glasses so you can watch all the nighttime animals come out and do their thing.”

“Nocturnal animals,” I say, eyeballing the suspicious spot. “Not nighttime.” It’s too dark to see much, but there’s nothing to indicate anyone or anything was ever here, besides us.

“And you’re smart, too,” she trills, grinning at me over her shoulder.

I stick out my tongue.

“Remember how much you loved that place when we were little? You got left behind on that field trip and didn’t even care.”

I was seven years old and stranded at a biodome, but I didn’t mind. Seeing my classmates file out behind the teacher and parent helpers, I’d crouched behind a giant hosta and watched them disappear. I counted as high as I could until they were gone, and then I’d finally explored the biodome on my own, choosing my own path, charting my own course, however briefly.

“It’s only eight o’clock,” Becca adds, her voice carrying through the dark forest. “And there’s that diner across the street with cinnamon buns the size of your head. Maybe we can get one after.”

There’s no point arguing. She’ll just get us lost in the woods and nag me until I agree. I trudge after her. “Okay, Becca. Awesome.”

“They have those fishbowl margaritas, too,” she calls. “We’ll get a couple, to celebrate your new job. My treat. I’m proud of you!”

Order The Book

Carrie wants a normal life.

Carrie Lawrence doesn’t need a happily ever after. She’ll just settle for “after.” After a decade of helping her sister hide her victims. After a lifetime of lies. She just wants to be safe, boring, and not trekking through the woods at night with a dead body wrapped in a carpet.

Becca wants to get away with murder.

Becca Lawrence doesn’t believe in happily ever after because she’s already happy. She’s gotten away with murder for a decade and has blackmailed her sister into helping her hide the evidence—what more could a girl want?

But first they have to stop a serial killer.

When thirteen bodies are discovered in their small town, people are shocked. But not as shocked as Carrie, who thought she knew all the details of Becca’s sordid pastime. When Becca swears she’s not behind the grisly new crimes, they realize the town has a second serial killer who has the sisters in his sights, and what he wants is . . . Carrie.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

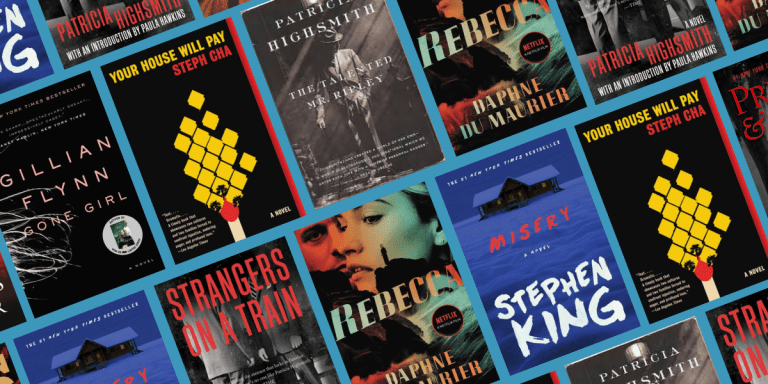

What to Read Next