Read the Excerpt: Mango, Mambo, and Murder By Raquel V. Reyes

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER ONE

“¡Basta, Alma! I told you I’m not doing the show.” I accentuated each word with the knife I held in my hand before I stabbed the packing tape and sliced open box number five of forty-eight.

“You are perfect for it. And come on, Miriam, what else are you doing?”

I narrowed my eyes and glared at my best friend, Alma. “¿Qué es esto?” I waved my hand like a hostess showing someone to their table. “Is this house going to unpack itself?”

“Porfa, this is not going to take all week. The cooking spot is next Friday. Today is Tuesday. You have a week and a half. It’s a short cooking demo on a morning show.” Alma shook her pinched hand like a stereotypical Italian grandmother. Except, of course, she wasn’t Italian, and neither was I. We’re Cuban-American. Both cultures talked with their hands. Or, in my case, whatever was in my hands at the moment.

I crumpled the New York Post page that wrapped a chipped green dinner plate. Before placing it on the stack that was building in the cupboard of my new Florida home, I shook the plate like a tambourine, “But, I don’t cook!”

“You do cook. Your cooking is excellent.” Alma, dressed in a sleeveless white dress, stepped away from the mound of newsprint about to tumble off the quartz countertop. This was the most expensive kitchen I’d ever had the luck to possess. The biggest, too.

“I am not a celebrity chef. I am an academic. Find me a job at a university.”

“Do you want to work-work? Or work-parent? I thought you said you were taking a little time off to be a full-time mom.”

“Roberto wants me to stay home for a year. At least until Manny is ready for school.”

“That makes the UnMundo morning show super for you. You need to do it. La Tacita is perfect for you. One morning a week, and you get a paycheck.” Alma raised her shoulders to her ears and flicked her palms out in a voila.

“But I’m not a chef. I’m a food anthropologist.” I felt heat building in my chest.

“Casi igual.” Alma dismissed my protest and checked her phone which had just beeped a notification. “The Women’s Club luncheon is in forty-five minutes. Hurry up and get ready, already.”

“I told you, I. Don’t. Want. To. Go. I know it’s important for you and your real estate business but come on, Alma. ¿Qué carajo am I going to do while you’re talking bayfront views and terrazzo floors with ladies that lunch?”

“Get dressed. Your mother-in-law will be here any moment to babysit.”

“You conspired with my mother-in-law? That’s a cardinal sin!”

“Amiga, you gave me no choice. This town works on connections. If you want Manny to get into the best school, then you need to make nice with the women that run this town. Lo siento, but that’s the way it is.”

“Manny is going to go to St. Brigid’s.” I chucked the empty box in the corner with the others. A cardboard fort was in my son’s near future.

“All the more reason to go to this lunch. The president of The Patricians will be there. It’s not like it was when we were little and going to St. Joe’s. Any tithing family was guaranteed spots for their children. Now, it’s who you know and how much money you give to the booster club.” Alma looked at Miriam. They’d been friends since kindergarten and Alma knew that look- jaw set, duck lips and squinting eyes. “If a fly crosses your face, it will freeze like that. Wrinkled and puckered is not a good look on you.”

I threw a wad of used packing tape in Alma’s direction. She swatted it away like Serena Williams returning a volley. The ding-dong-dwong of the doorbell had barely finished when my mother-in-law appeared in my unfurnished living room. My mouth was faster than my good sense. “Did I leave the door unlocked?” My tone didn’t help either.

“Well, hello to you, too.” Marjory Smith, my husband’s mother, posed at the edge of the unpacking chaos like an egret about to peck a lizard from a shrub, and that lizard was me. A petite woman with a frosted blonde bob, she wore bright red pedal pushers, a light-weight pink sweater set, and black flats with a metal monogram on the toe. From my little time in Coral Shores, a 1950’s time-warped village within the city of Miami, it appeared to be the standard-issue uniform of women over the age of fifty-five. The shoes came in all colors, but the brand was always the same.

I kicked myself for having stepped into it again and hurried to give my mother-in-law a hug. “I’m sorry for being rude. Hello, and welcome.” The hug was about as warm as an icicle on a Vermont cabin in February. Marjory barely tolerated me. Giving her a grandchild was my one and only credit. By contrast, the embrace Marjory gave to Alma was like butter on bread fresh from the oven.

“So, good to see you again, Mrs. Smith,” Alma cooed.

“Call me, Marjory, darling. Over the years, you’ve earned enough commission off me and my friends to put us on a first-name basis.”

They both laughed hollowly.

“Yes.” Alma squeezed Marjory’s upper arm. “Thank you for the Fleming referral. Their house is gorgeous, and I may already have a buyer for it.”

“Oh, that’s good news, dear.” Marjory jangled a set of keys hooked in her hand, making a show of them before slipping them into her pocket. “Miriam, please tell me you’re not wearing that to the country club.’

I stuttered like a beater car cranking on an empty tank of gas. “I…I…I…”

“She was headed to her bedroom just as you walked in.” Alma put her arm around me like I was a lost child. “You were asking me for my opinion, right? The bold print dress or the light blue suit. What do you think, Marjory?”

“Understated is always in good taste.”

“Sage advice. I agree. The suit it is. Come along, Miriam, we need to be there in thirty minutes.” Alma pushed me down the unlit hall.

“How did she get a key to my house?”

“I don’t know.” Alma shrugged and avoided my suspicious stare. “Hurry up.” She went to the closet and pulled out my one summer-weight suit. It had a short jacket that fell just below my waist. I’d worn it to defend my dissertation because it made me look a little like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. I had needed all the confidence I could beg, borrow, or steal. One of the professors on my committee was a not-so-closeted misogynist that lumped all Spanish-speakers into one heritage, Mexican.

“You gave her a set?!” I stripped out of my shorts and NYU T-shirt. “Please tell me you didn’t give her a key to my house!”

“I didn’t give her a key, but that’s not to say that she didn’t get a set at the closing.”

“Caridad, por favor, save me from that bruja.”

“Witch or bitch, she did buy you a house.”

“She bought her son and grandson a house. A bribe to get Robert down here. I was happy in New York. I was in line for a professorship.” I heard the whining in my voice. “I didn’t want to move three blocks away from my mother-in-law.” I fake-sobbed, and Alma ignored me completely. She didn’t give me even half an ounce of sympathy.

“Ponte las pilas. We should have been there already.” Alma twisted the rod on the temporary window blinds. “Your backyard demands a pool. I have a guy. Best pool contractor in all of Dade County.”

I sat on the side of our full-size bed and buckled the straps on my heels. “We don’t have that kind of money.”

“You don’t have it now, but you will soon. My guy has an eight-month waitlist, and permits take forever. Trust me, Miriam, you need to get on it.”

“Later. Maybe when Manuelito is older. Besides, swimming pools are dangerous with little kids in the house.’

“Kids? No me digas— You’re pregnant?” Alma looked away from the window and gaped at me.

“No.” I stood and went to the bathroom to apply eyeliner and lipstick. “But Robert’s been dropping hints about Manuelito needing a little sister.”

“I’ll go ahead and make the appointment with my pool guy.”

“No. For reals, we can’t afford it.”

“Let Marjory give you the pool as a baby shower present.”

“Like I want to owe her more. No! The down payment and co-signing are bastante.”

“Fine. But you know, Roberto is going to be making the big bucks.”

“I can’t believe he took the job. It is so opposite of everything—Whatever. I can’t think about it. We’re here. We have a roof over our heads. It is all going to work out. Right?!”

“Yes.” Alma said it like, “Duh!”

“How do I look? Can I fool these old ladies into thinking I’m upper-crust and not a Cubanita from blue-collar Hialeah?”

“Dr. Miriam Quiñones-Smith, you have nothing to be insecure about.”

CHAPTER TWO

On the carpeted dais of the country club’s Flamingo room stood a skeletal septuagenarian in a mauve skirt-suit. With her boney legs and knock knees, she certainly favored the iconic Florida bird. She warbled an off-key aria that made me think of the waterfowl shaking a shrimp down its long neck. Alma turned to me and whispered, “I told you these lunches were entertaining.” Alma was used to the tawny enclave of Coral Shores. It was her chosen hurting grounds. I was too stunned to enjoy the farce. When the high D crescendo finally came, my eyes watered. The rose and carnation centerpiece wasn’t stirring up an allergy; my ears were in pain. The banquet room burst into applause. I dabbed the tears from my eyes and joined the ovation.

“Gracias a Dios that’s over,” I said from behind a plastered grin. Alma laughed but not loud enough to draw attention to our mockery. “I can’t believe you dragged me to this circus. You know I can’t stand clowns!”

“Shhh. They’ll hear you.” Alma sat and arranged her napkin in her lap. A small army of bow-tied servers swooped towards us with plates. “Oh, look, lunch is served. I can’t wait for you to try this chicken salad, Miriam. It’s the club’s specialty.”

As if I hadn’t guessed from her sarcastic tone, the salad was a travesty. It had more mayonnaise than meat. And the celery was mushy when it should have been crunchy-crisp. My taste buds rioted after the first bite, and I set my fork down. I buttered a piece of stale, hard bread and looked around the table. The lady to my right, the only other attendee under sixty beside Alma and me, was not eating her lunch either.

“Not hungry?” I asked.

“No.” She pushed the salad away from her.

“Hello, I’m Miriam.” I offered her a handshake.

“Nice to meet you.” She clamped my hand weakly, then let go. “Excuse me.” The woman pinched her temples.

“Headache?”

She nodded and pointed to the back of the room. “Ladies’ room. Be right back.”

I watched her walk away, a little unsteady on her feet. She stopped to talk to a tanned woman with short black hair wearing tinted eyeglasses. The lady gave her something, an aspirin, I hoped.

“Miriam, meet Olive Morgan. She’s a member of St. Bridgid’s Patricians,” Alma said.

I smiled at the older woman next to Alma. She had light gray hair, and her pink lipstick was badly applied.

“Excuse me, I need to visit the ladies’ room,” Alma said as she got up to leave the table.

“Alma tells me you have a little boy?” The woman’s head bobbed with a touch of palsy.

“Yes, he’s four,” I said.

“They are little rascals at that age. My daughter, Daisy, teaches the four to six group on Sundays. I haven’t seen you at church yet.” A blob of chicken salad launched from her fork. The poor woman shook like she was over ninety. Maybe she was. Only a ninety-year-old would use the word rascals. I immediately pictured Manny in suspenders and a newsboy cap.

“No, we haven’t made it yet. I’m still unpacking from the move.” Thinking about the warning Alma had given me, I added. “But we will soon. I promise.”

“Goody-good-good. I’ll tell my Daisy to be expecting you,” Olive said. Her pink lips were now white with mayonnaise.

The young lady with the headache returned with Alma only a few steps behind her.

“Did you find an aspirin?” I asked.

“Yes, thank you,” she said with a sniffle. She used her napkin to daintily blow her nose before pouring a black packet of powder into her water glass. The powder turned the water a faint shade of pink before it dissolved completely. She drank the mixture in its entirety.

Alma went clockwise and introduced me to the other ladies at the table. When she got around to the lady with the headache, it dawned on me she hadn’t told me her name.

“Are you okay? Is your headache worse?” I asked, preempting Alma’s introduction. The woman looked sweaty and bluish. Before I could grab her, she collapsed face-first into her lunch. The splat her forehead made when it landed in the mound of chicken salad was almost as loud as the club members’ gasps.

“Call 9-1-1,” the lady with a skunk stripe of white roots at the adjunct table yelled, “Sunny’s fainted!”

“I’m sure she’s on another one of her crazy diets. Sit her up, and I’ll force a Coca-Cola down her,” said a stylishly dressed woman from the table in the farthest corner of the room. I watched as she walked with confidence and grace towards our table. She didn’t fit the mold of the Women’s Club membership I’d seen thus far. Her face was youthful, but her hair was unabashedly steel gray. She had it coiffed in an asymmetrical swing bob. She wore black wide-legged pants with a boho knit sweater over a white V-neck shirt. It was effortless, sophisticated-casual, and reeked of wealth. The four bands of multi-carat eternity rings on her finger also pegged her for one of the founding village families.

I asked Alma who the lady was, and she told me. “Stormy Weatherman, Sunny Weatherman’s mother.”

“Sunny is the lady in the chicken salad?”

“One and the same,” Alma replied and then switched to Spanish to tell me the relevant gossip of the tableau.

After the initial gasp of horror at the faux pas of planting one’s face into one’s lunch, the ladies that lunch did not seem too troubled by the event. And what Alma told me in the few seconds before Stormy reached her daughter’s side explained why. Sunny was addicted to diets and exercise fads. She was often seen running around Coral Shores in the mid-day sun with her concaved midriff showing. Her dietary and athletic regiment also caused her to faint—a lot.

Fire Rescue marched through the heavy twelve-foot oak doors carrying their medical equipment just as Stormy made it to Sunny. Due to the conjunction of Florida, golf, and middle-aged men that drank more beer than water, Fire Rescue always had a truck parked in the country club parking lot in case of heatstroke and lighting strike. Or so Alma told me.

“Don’t worry. I’m sure she’ll rouse in a moment,” Stormy called out to the rescue team. She patted her daughter’s back, and then she shook her by the shoulders. Her shaking became more animated, and Sunny’s head lolled from side to side in the chicken salad, making a squishing sound like bare feet in mud. “Did you bring the defibrillator?” she asked the blue and red uniformed team. “It looks like she might have gone and done herself in this time.” Stormy spoke in a calm and matter-of-fact tone as she moved away from the body to make room for the EMTs.

Alma, our tablemates, and I had already moved several feet from the scene of the trauma. Stormy’s demeanor alarmed me. If it were my child lying lifeless, I would be in hysterics. I whispered as much to Alma, in Spanish. I made the sign of the cross to keep Manuelito safe.

“Well, you have to understand Stormy and Sunny’s history,” Alma said. “The girl has been nothing but trouble and angst since age thirteen. She’s been in and out of rehab, been to every ashram in India, California, and New York. Miriam, esa niña es una vergüenza.”

I sucked my lower lip and made an “uh” sound in recognition of the sad situation. It was a shame when a family member had gone astray despite the family’s best help and love.

The whole room watched as Sunny’s limp body was laid on the sled-shaped carrying board the team had placed on the banquet hall’s paisley carpet. Nobody bothered to wipe the chicken salad from Sunny’s face. She looked like a spa patron with a lumpy oatmeal masque. Suddenly, the action around the passed-out woman shifted. It changed from the basic first response of taking a pulse to the this-is-serious opening of plastic-encased medical equipment. One of the team members called “Clear.” The round paddles of the defibrillator were placed on Sunny’s still chest. The machine wound up and popped its charge. Nothing. The crew hit her with another bolt of electricity. It must have gotten the expected results because the rescuers lifted the board she was strapped onto and carried her to a waiting stretcher in the country club’s main hallway.

The Women’s Club, or at least those of us that didn’t need walkers, followed the stretcher. We watched as the ambulance pulled out of the parking lot with its sirens wailing. Stormy waited for the valet with the same measured pace and unruffled manner I’d seen in her earlier. It made my heart ache that a mother had seen her child put into an ambulance so often that it no longer caused a panic. She got in her silver Cadillac coupe and drove after the emergency vehicle. Alma locked arms with me. So as not to step on the heels of the crowd of shuffling matrons, we did the bridal walk. Step. Pause. Step. Pause. “No te preocupes. I am sure she will be fine,” Alma reassured me, but I wasn’t so sure.

By the time we were back in the meeting room, the chairs had been straightened, and Sunny’s mangled salad had been removed. The waiters busied themselves with clearing the main course. Coffee and dessert were quickly served, and the gavel summoned the group to order. I played at eating my pastry but had lost all appetite for anything other than a sip of water. The business part of the club meeting went by with slurps of coffee and scrapes of forks on china. I pushed my cheesecake around the plate while the president, a waspy lady in a brown sheath dress with a knotted string of pearls, gave the rally cry for the club’s annual fundraiser. The theme for the year was the Caribbean. The cause was to feed the children stricken by the hurricanes that had hit the islands of Puerto Rico, St. Marteen, and Dominica.

Alma elbowed me and whispered, “You should be on the steering committee for the event. You’d add some sabor y sazón to it.”

I shook my head a controlled but adamant, “No way, estas loca!”

“I’m going to nominate you. You’re perfect for the job with your degree in Caribbean food,” Alma said. She raised her hand to gain the floor. I quickly spilled my glass of water into her dessert plate, causing her to forget her insane plan in lieu of saving her silk suit.

In the car, Alma asked, “What were you thinking? You nearly ruined my best suit.”

“What was I thinking? What were you thinking? I’ve been here less than two weeks, everything is still in boxes, I have to find Manny a pre-school, and I don’t know anyone other than you and my in-laws. Plus, those ladies are sooooo…”

“Lost in a time-warp? I know it’s a little 1950’s, but that is exactly why they need new blood like you and me,” Alma interjected. Her enthusiasm for her adopted town was admirable. She and I were Cuban-American and raised ten miles away in the Latino stronghold of Hialeah, Florida. Coral Shores might be in the same Miami-Dade County, but it was culturally a world away, no, a galaxy away.

“No, what I was going to say was white!”

“Miriam Quiñones Smith, you married a WHITE man from this very town.”

“I know. I know. But we were in New York and in college, and the city makes everyone more appealing.”

Pulling into the circular driveway of my new home, she came to an abrupt stop. With great concern, Alma looked me in the eye. “Are you and Roberto having problems?”

“No, I don’t think so, not really. It’s just been stressful. He’s busy with work. When he does have free time, he goes golfing with some old friend I’ve never heard of and – well, I never knew he even played golf! And then my suegra is driving me crazy. She insists on calling Manny by his middle name, Douglas. I hate that name! I only agreed to use his grandfather’s name as an appeasement to Robert. And I want a job, but Robert keeps telling me to hold off on my search until next fall when Manny is in kindergarten. That’s a long way away.” I began to sob.

“Cógelo suave. You just got here. Give yourself a break. Get settled in.” Alma unbuckled her seatbelt and reached across the armrest to hug me.

A knock on the passenger side window startled us into peeping like chickens caught by a swooping hawk. I mouthed to Alma, “See what I mean?”

Alma lowered the window with the push of a button. The once silent yakking of the petite ash-blonde blue-eyed monster, a.k.a. my mother-in-law, a.k.a. Marjory Smith, became audible.

“Douglas is down for his nap. Thank goodness. I love the dear, but boy, does he have a set of lungs. Miriam, you have to work on teaching him to use his inside voice. How was the lunch? What did I miss?” She bombarded us with queries. I was afraid she was going to climb into the car via the window. She pulled on the door handle several times. Each time it fell with a soft clang. Alma unlocked it after the third attempt. I hurriedly got out of the car, thanking Alma for the outing. I excused myself with a made-up need for the bathroom. Marjory circled to Alma’s window. As I slipped through the front door, I looked back over my shoulder and saw Alma’s selling skills take control of the interrogation. She had my mother-in-law silenced as she reported the highlights of the luncheon. Alma was smiling and gesturing and giggling with the light air of a spokesmodel.

When I emerged from straightening the smudges of eyeliner my sobbing had caused, my mother-in-law was gathering her things to leave. I was thankful I wouldn’t have to entertain her for the afternoon. I knew Manny was the reason for her quick departure. She’d insisted on babysitting so I could go to the Women’s Club despite the fact that she really wasn’t a toddler lover. Marjory liked children when they were well-behaved, which four-year-olds rarely were. But before she escaped, she gave me a tirade about Stormy’s lack of control over Sunny. Her tone was disapproving and condemning of Stormy. Obviously, the women had a history. I was slightly curious but not enough so to ask my mother-in-law to stay.

Order the Book

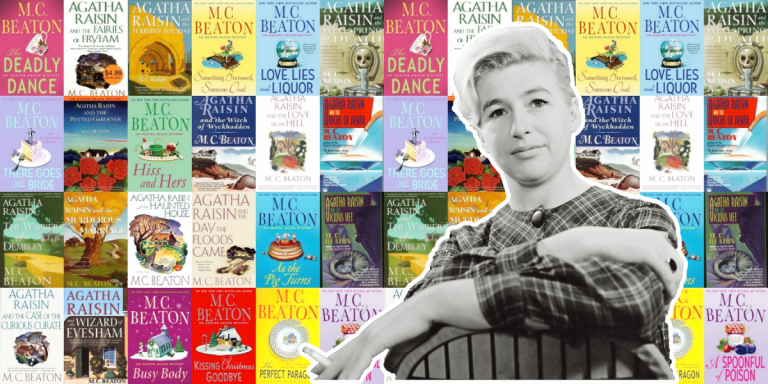

Food anthropologist Miriam Quiñones-Smith's move from New York to Coral Shores, Miami, puts her academic career on hold to stay at home with her young son. Adding to her funk is an opinionated mother-in-law and a husband rekindling a friendship with his ex. Gracias to her best friend, Alma, she gets a short-term job as a Caribbean cooking expert on a Spanish-language morning TV show. But when the newly minted star attends a Women's Club luncheon, a socialite sitting at her table suddenly falls face-first into the chicken salad, never to nibble again.

When a second woman dies soon after, suspicions coalesce around a controversial Cuban herbalist, Dr. Fuentes—especially after the morning show's host collapses while interviewing him. Detective Pullman is not happy to find Miriam at every turn. After he catches her breaking into the doctor's apothecary, he enlists her help as eyes and ears to the places he can't access, namely the Spanish-speaking community and the tawny Coral Shores social scene.

As the ingredients to the deadly scheme begin blending together, Miriam is on the verge of learning how and why the women died. But her snooping may turn out to be a recipe for her own murder.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next