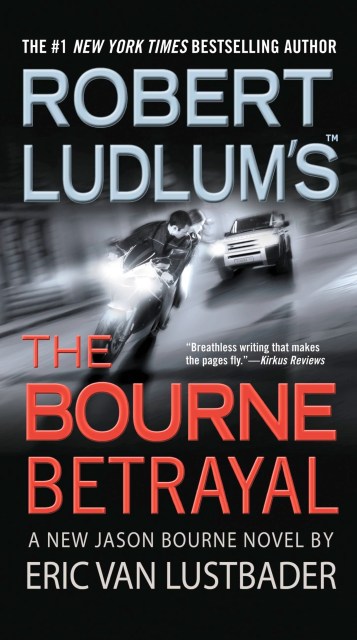

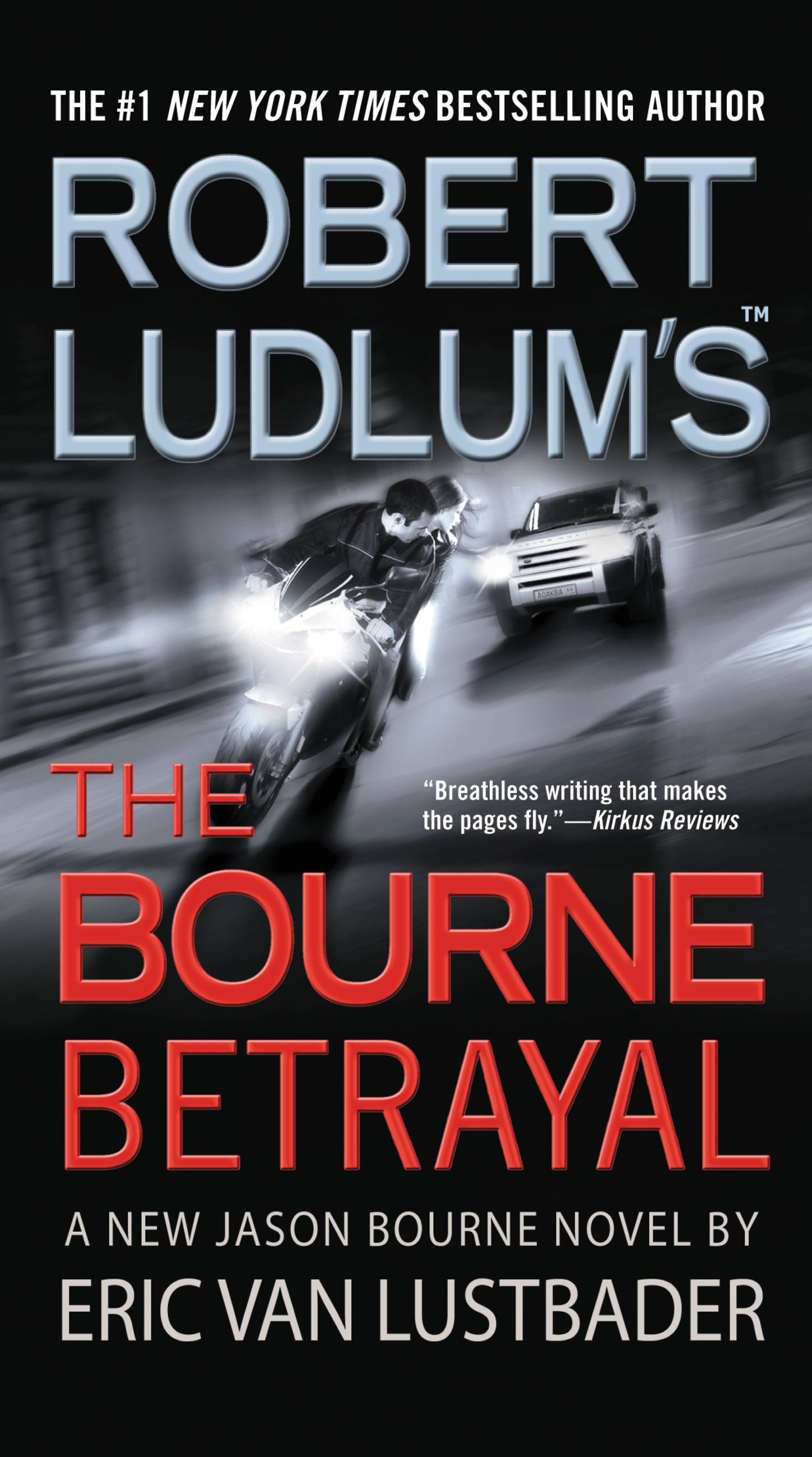

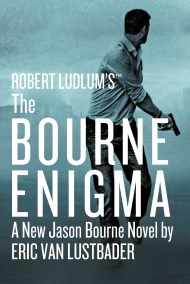

Robert Ludlum's (TM) The Bourne Betrayal

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

New York Times bestselling author Eric Van Lustbader bring another pulse-pounding Jason Bourne thriller as Bourne’s last friend in the world goes missing and Bourne will do another to bring him home.

Series:

- On Sale

- May 1, 2008

- Page Count

- 736 pages

- Publisher

- Vision

- ISBN-13

- 9780446618809

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use