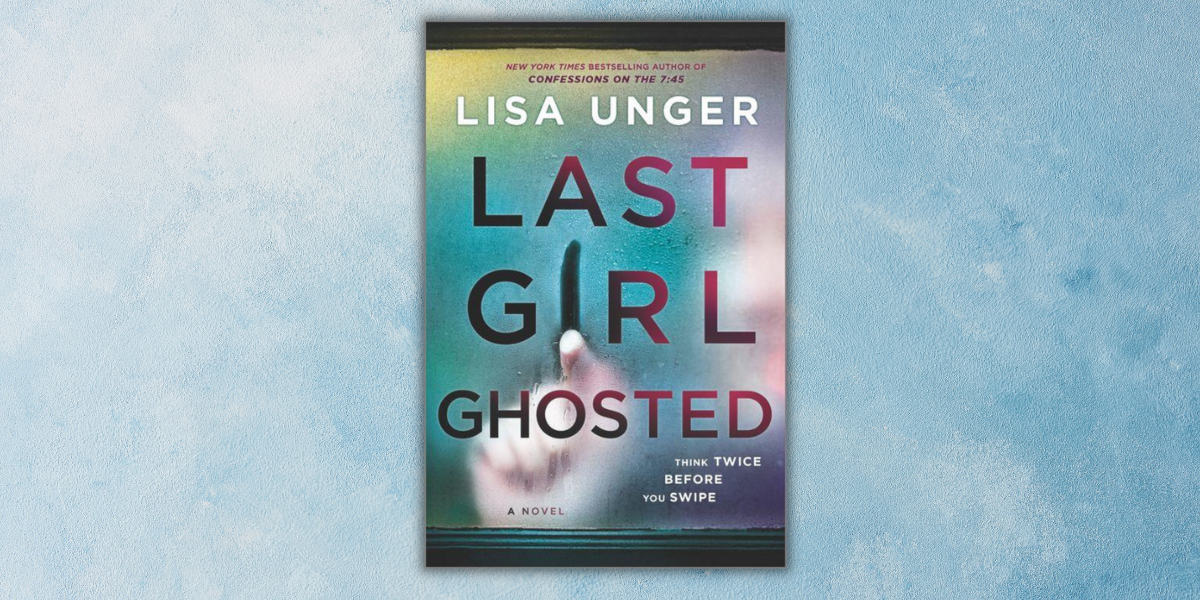

Read the Excerpt: Last Girl Ghosted by Lisa Unger

prologue

prologue

mia

Mia Thorpe drove, the road ahead of her long and twisting. Dark. She’d been driving on and off for two days, was stiff and bleary-eyed from the trip. She’d stopped last night at a motel for a fitful sleep, half-waiting for word from Raife that didn’t come. Don’t worry if you don’t hear from me, he’d told her. Cell phone service is spotty. Just follow the directions. I’ll be there when you get there.

She believed him. She trusted him. She did.

She’d lain on the hard, uncomfortable mattress in a motel room that smelled like cigarette smoke and industrial strength cleaner. Each time she’d managed to drift off a passing car would cast its headlights on the wall beside her bed, shining through the too-thin curtains, waking her. She doubted if she’d nabbed two solid hours.

She was on the road again before the sun rose.

“I think I love him, Mom,” she said out loud. Though her mother was long gone, Mia was sure she was still listening.

When Mia was six years old, she wanted to change her name to Princess Rainbows. She knew that it was possible to change her name because her dad told her that when she was grown up she could change her name to whatever she wanted. But while she was still his little girl, he would very much like her to keep the name that he and Mommy gave her.

A name is like a gift, he told her. We gave it a lot of thought and picked something we thought was as beautiful as you are. Mia Belle Thorpe. And technically, isn’t Belle a princess name?

That was true. But there were three other Mia’s in her class, and one other Belle. And a Bella and an Isabella who liked to be called Izzy. Mia Belle Thorpe wasn’t like Mia with the red hair who frowned miserably at her corner desk, and cried all the time. She wasn’t like the Mia who was really good at math and always shot her hand up like a rocket when it was time to volunteer to solve problems at the board. And she definitely wasn’t like shy Mia who was pale as an egg and never spoke at all, was frequently absent.

She was Mia, herself. She didn’t want to be one of four Mia’s in the room. The teacher, to avoid confusion, took to calling them by first and last names. Mia Thorpe. She remembered hating that. She couldn’t even say why.

Maybe it started then, this idea that she had to assert her “specialness.” Her mom always told her she was special—that she was pretty, and smart, and a ray of sunshine. There’s no one like you, little star. You’re my special girl. But how could that be true if there were three other Mia’s in her classroom alone? Mia Belle Thorpe was pretty sure

then that no one else in the world was named Princess Rainbows.

Around this same time, she discovered the wild pleasure of slamming doors in anger. So after another argument erupted, over her afternoon snack where she’d listed all the ways in which having the same name as three other people had annoyed or inconvenienced her that day, her mother ended it by saying: Mia Belle Thorpe, we will not discuss this further. You are not changing your name to Princess Rainbows. Now please go do your homework.

Mia had stormed up the stairs, and slammed the door as hard as she could, making, it seemed, the whole house vibrate with her misery. She lay on her bed weeping, and must have fallen asleep because when she woke up, the afternoon had turned to dusk. The light in her room was an unfamiliar gray.

She and her mother rarely argued. Mia might get very mad at her dad for being bossy, or for tooting, or for trying to help with math when he really had no idea what he was doing. But her mother was soft and sweet, rarely said no, always knew how to fix anything that was wrong, and consistently smelled like flowers. And when Mia woke up, she felt regretful for storming off and slamming the door so hard.

The house was quiet when she left her room. Which felt odd. Because usually she heard her mom in the kitchen—cooking, or talking on the phone with a friend, or listening to the radio while she made dinner. There were all kinds of familiar noises in the house. But silence was not one of them.

She crept down the stairs. It was easy to apologize to her mother; she knew it would be accepted with hugs and a kind conversation about why things couldn’t be the way Mia wanted them to be. There would be some consolation prize—maybe a cookie, or a concession on another matter of conflict.

But when she entered the kitchen, she found her mother lying on the floor. One of her mom’s red velvet flats had fallen off her tiny foot. And it looked just like she was sleeping.

Mom, she said, sitting down beside her. Mommy. I’m sorry.

But her mom didn’t stir, and Mia lay down beside her, rested her head on her chest. She knew that something was horribly wrong. But she pushed it so deep, squeezed her eyes shut and held on tight. She was sleeping. She’d wake up very soon.

That’s where her father found them when he came home from work, not long after. The sound of his wailing would stay with Mia for the rest of her life.

It’s not your fault.

This was the single phrase she heard most often after that day. From her father, from therapists, from aunts and uncles. But Mia knew how much her mother hated when she slammed the door. Truth be told, that’s why she slammed it harder than she had ever had before. And so no matter how many times people told her it wasn’t her fault, she knew that it was.

Mia’s mother had asthma; they’d recently had to change her medication. She’d ignored warning signs—shortness of breath, dizziness. She’d had a heart attack. No one’s fault, not really. But Mia knew that being upset could aggravate her mom’s asthma.

She wasn’t upset, her father, Henry, told her. She called me after you fought. She said, Princess Rainbows is at it again. We thought it was funny, cute. She wasn’t mad at you. She was never mad at you.

Mia didn’t believe him.

And while she loved her father, it was true that she loved him somewhat less than she loved her mother. It was also true that a very special kind of light that her mother brought into her life, and into her home, went dark. Though there was still light, it wasn’t anything like the light that came from her mother’s love. And her father, who had always been goofy and funny and full of laughter, with big appetites, and grand ideas, and big plans for day trips and vacations, seem to deflate, go pale and quiet.

The world should have ended. It did end for Mia and Henry in all sorts of ways.

It just didn’t for anyone else. They both went on in that unfamiliar gray light together with the person they loved less than they had loved her. It wasn’t until years later, in rehab for the first time, that Mia Belle Thorpe worked to unpack this moment of her life. How everything that went wrong later for her, started there; how every moment after was colored by the loss of her mother. She was special after that. She wasn’t math Mia, or shy Mia, or grouchy Mia. She was Mia whose Mommy had died.

Mia Belle meant my pretty, or my dear one. It was special because it was the name her mother had given her. She wished she could tell her mother that she knew that now.

Now.

Now, the farther she went on the dark road, the more of herself she left behind. All the people she’d been—the pampered little girl, the child who’d lost her mother, the angry teenager, the addict, the recovering addict, the person struggling, always struggling to find the specialness she’d seen reflected in her mother’s eyes.

You were special to her. You are special to me, her father told her. That’s the only special anyone needs to be.

She’d left everything that tethered her to her life behind. She hadn’t called her father to say goodbye. He didn’t like Raife and he didn’t understand their relationship, so there was no point in fighting about her plans. After a while, she’d send him a letter, explaining.

She imagined that it would be a relief to have some distance, for both of them. Her father had a girlfriend now; she seemed nice, had reached out to Mia multiple times. But no. Just no. Maybe if Mia and her father had some space from each other, from the memory of their shared loss, they could each be happy for a while. She loved her father. But it didn’t make her happy to be with him. She strongly suspected that he felt the same way about her.

Let’s leave the toxic modern world behind for a while. Maybe not forever. But for now, I know a place where we can be free. That’s what Raife had said to her when he issued his invitation.

It sounded right to her.

On this dark road, with just a burner phone she’d picked up at a drug store, all the chatter had gone quiet. There were no social media notifications, no constant pinging announcing the ugly news headlines, or junk emails. No endless texts from friends with memes and plans for the evening. There were no podcasts. No Siri to ask about the weather— or whatever.

The car she’d picked up in the lot, as Raife had directed her, just had an AM/FM radio. As she drove, the stations she could receive changed. A country music station faded away into static. She cast about and found some classic rock station with a mouthy DJ that eventually devolved into white noise, too. For a while, all she could get was a Christian sermon filled with fire and brimstone. She listened for miles, just because she found that she was afraid of silence.

She had the map he’d left her, figured how to use it. He’d marked on the map where she should stop for gas. No cameras. Pay cash.

But slowly, she learned to let the quiet wrap around her. Finally, the nervous chatter of her mind quieted, as well.

She hadn’t seen another car for hours. Above there were only stars and stars and stars, until the light of the rising sun brightened the sky. She didn’t know the place she was going. Or how long she would be there. But she knew that for the first time in her life, she could taste

freedom.

one

Now

Modern dating. Let’s be honest. It sucks.

Is there anything more awkward, more nervous-making than waiting for a person you’ve only seen online to show up in the flesh?

This was a mistake. The East Village bar I’m in is crowded and overwarm with too many bodies, manic with too many television screens, the din of voices, somewhere music trying in vain to be heard over the noise.

I’m early, which has me feeling awkward and waiting on something I’m not sure I wanted in the first place. I started off standing by the door, half-planning to leave, then finally made my way into the fray and slipped into an open place at the bar.

And here I sit on an uncomfortable stool. Waiting. I should go.

My order of a seltzer water has earned me the indifference of the pretty, tattooed bartender with the hot pink hair and magnetic eyelashes, and she hasn’t been back since briskly placing the tumbler in front of me. She has a point. There’s no reason to come to a place like this—a hipster watering hole at happy hour—unless you’ve come to have a drink. One certainly doesn’t come for the atmosphere. But it’s important to keep a clear head. I’ve never been here before. My best friend Jax suggested it,

an old haunt of hers. Crowded, she said, anonymous.

Safer to meet a stranger in a crowd, right?

Safer not to meet a stranger at all? had been my reply. A worried frown. And then what? Never meet anyone?

Would that be so bad? Solitude. It’s not the worst thing in life. It was Jax’s idea. The whole online dating thing.

Robin, my childhood friend, who is basically Jax’s opposite, was against it. Love, she said, is not an algorithm.

Truth.

Anyway, who’s looking for love?

Only everyone, Robin would surely say.

I take a sip of my icy sparkling water and glance at the door. A roar of laughter goes up from the big group at the table in the back. I keep my eyes on them for a moment, watching. Three women, four men, young, well-heeled, coiffed and polished— coworkers maybe? Relaxed, easy, comfortable. The opposite of how I feel. I notice that my shoulders are hiked up. I force myself to relax, breathe.

The man beside me is uncomfortably close, his shoulder nudging up against mine twice, now three times. Is he doing it on purpose? I turn to see. He’s bulky, balding, a sheen of sweat on his brow. No. He’s not even aware of me. He’s on his phone, scrolling through pictures of women.

It’s that other app, Firestarter, the one just for hookups. It tells you who is in your vicinity, looking for a brief, no strings connection. There are people all around him, an attractive brunette alone at the end of the bar, also staring at her phone, a group of young girls—students judging from the New School sweatshirt and the pitcher of beer—at a high top right behind him. He’s on his second scotch at least, I determine by the empty glass next to his full one. But he just keeps scrolling through the images on his phone, looking and looking.

Strange. The world has become a very strange place.

Venturing another glance at the door, I watch a group of three young men walk in, floppy hair and skinny jeans, unshaven, one of them sporting that giant beard some guys seem to favor these days. It’s like he has a bush on his face. But there’s something virile about it, too, isn’t there? Very Game of Thrones.

This will be my third meeting from the dating app Torch, which according to Jax is the only way that people meet these days. She set up my profile, helped me figure out how to scroll through the guys who had posted their photos. Jax likes them buff and dumb; me, I’m partial to geeks. Bookish men in glasses, people who read and think, who hike, meditate.

Needless to say that’s the minority on Torch.

My first date was with Drew, an actuary and a Russian literature enthusiast. We met for sushi, got a little drunk on sake, and I spent the night at his place, a Lower East Side walk-up. I snuck out in the morning while he snored loudly.

As far as Jax was concerned, this was a successful outing. But it left me feeling a little hollow. Not sure if I’d been used, or done the using. He didn’t call, and, the sad thing was, I didn’t even want him to.

My glass is empty. I catch the bartender’s eye and point. She gives me a curt nod.

“Another seltzer?” she says, taking my empty glass.

I press a twenty across the sticky bar and her demeanor changes palpably. She works for tips after all, and I’m taking up valuable real estate for a soda water drinker.

“Thanks,” I say when she hustles my drink back, this time with a generous twist of lime.

My second Torch hookup was with Bryce, a yogi and a meditation instructor. He was—very flexible. We went to a vegan place in SoHo and spent the night together in his minimalist Williamsburg loft. He called once, twice, three times.

I feel a connection, he said in this text. I didn’t.

I’m ashamed to say I never even answered him. Jax assured me that this was the way of it. People expected to never hear from each other again.

Look at it this way, said Jax. You’ve gotten more action in two weeks than you have in two years.

Sadly, she’s right.

Another glance at the door, which is disappearing in the growing crowd. Really. I’m gonna go.

Tonight, I’m waiting for Adam. A technology expert with a penchant for Rilke and Jung.

This guy? said Jax in dismay.

True, the grainy picture on the screen was not flattering— heavy brow, nose too big. The text was minimal to the point of being curt. Dislikes: shallow people. Likes: solitude. Personal mantra: Everything in NYC is within walking distance if you have enough time. Closing with: “You are not surprised at the force of the storm.” Only a Rilke geek would know that line and what it meant. It hooked me in a way the others hadn’t.

Who are you, Adam? I’m more interested in seeing you in the flesh than I should be.

But maybe you’re not coming. It’s still five minutes before our scheduled time, but probably I’m about to be stood up.

I text Jax: This is the last time.

Is he a dick? It seemed like he would be a dick. You can usually tell. Hasn’t shown up yet.

How early were you?

A half hour.

I am treated to the eye roll emoji. Just chill. You never know.

Have another seltzer, you lush.

I’m about to text her back when the door opens. There you are. I know you right away.

There’s a strange clench in my solar plexus at the sight of your face. A rush of recognition. From the photo I saw, yes. But something else. You’re taller than most of the men in the room, broad, muscular, in a charcoal blazer over a dove-gray T-shirt. Standing a moment, looking uncertain, you run a large hand through the thick mane of nearly shoulder-length, jet-black hair.

He’s here, I text Jax quickly. Gtg.

Is he hot?

Are you? Hard to say. Your nose is too big, eyes weirdly black at a distance. When you scan the room, your gaze meets mine. I smile but don’t wave. Maybe not hot in the classic sense. But something that has been dormant within me awakens.

That moment, it freezes. Everything around us pauses, seems to wait a beat. I feel my breath in my lungs as you push toward me through the crowd.

Just as you reach me, the guy in the next seat miraculously leaves and there’s a space for you to slip right into it, and you do.

I like your smile; it’s a little lopsided, sweet.

“Beauty and the beast,” you say, by way of introduction. I blush stupidly. “Adam?”

We shake hands. Your grip is warm and solid, gaze intense. “Nice to meet you, Wren.” Your voice is deep, almost a rumble. Then, after a quick assessing glance around the bar, “Is this

the kind of place you usually like?”

There’s a gleam of amusement, mischief in your eyes.

It’s weird. You’re so familiar, as though I’ve known you for years. A light clean scent wafts off you, the late autumn chill from outside still lingering on your clothes.

“No,” I admit.

“Then why choose it?” It could be confrontational, peevish.

Instead, it’s purely curious.

“I didn’t. My best friend Jax—she thought it was a safe place to meet a stranger.”

Your eyes linger, searching my face for I’m not sure what.

Then, “Is there a safe place to meet a stranger?” “Maybe not.”

Your smile deepens, and you lift an easy hand. The bartender rushes to do your bidding, coming quickly from the other end of the bar; you’re that kind of guy I think. A natural air of authority. People rush to do your bidding. You order a Woodford Reserve on the rocks, then look to me, inquiring. I shake my head, lifting my glass.

“But we’re not strangers, are we?” you say when the bartender has left.

I feel a little rush of uncertainty. “Are we not?”

You rub at that powerful, stubbled jaw. “It definitely doesn’t feel like it.”

“No,” I admit. “It doesn’t.”

When your glass comes, you lift it to me and I clink it with mine. The smile on my face is real, all my nerves and tension dropping away.

“To strangers who somehow already know each other,” you say. Your tone is easy, posture relaxed. You’re comfortable in your own skin.

“I like that.” “So do I.”

We’re shouting at each other over the din. You talk a little bit about your work in cybersecurity. I tell you that I’m a writer— which is the truth but not the whole truth. We are leaning in close to hear each other. My throat is starting to ache a bit from yelling.

Finally, you say, “Should we just get out of here?” “Where do you want to go?”

Is this just going to be another Torch hookup? Because I’ve decided I don’t want to do that again. Maybe it’s the way of it now, like Jax says. But if it is, then I’d rather be alone.

“Anywhere but here,” you say.

We don’t go back to your place or to mine. We just start walking, which, when the weather is crisp and the city sky is that velvety blue, is my favorite thing to do. We wind through the East Village to Lafayette, passing Joe’s Pub and Indochine. We cross Houston, wander through the garish lights and shuttered shops of Chinatown and end up on the Brooklyn Bridge, that lovely relic of Old New York.

We log miles and sometimes we’re talking about your childhood—lots of travel, about mine—isolated, unhappy. But some- times an easy silence settles. And it’s the silences that excite me most. The ability to be quiet with someone, there’s a delicious intimacy to that. In Brooklyn Heights we stop at a quiet bar near Adams where low jazz plays, and people talk quietly, huddled together in cozy alcoves in the near dark.

“This is more like the kind of place I like,” I say. “Me, too.”

You talk about work again. You own a cybersecurity firm, are new to the city after traveling extensively since childhood— first for your father’s work, then for your own. Various locations in the US, Europe, and Asia. I take in details—the expensive cut and material of your jacket. The manicured nails. How you stare when I speak, listening intently. You wait until I’m done talking, take a long beat, before answering or commenting. How you haven’t touched me, not even casually, though we’re very close together.

“I have an early morning,” I say finally. I don’t want to break the spell between us. But neither do I want to get glamoured into doing something I’ll regret. It’s too easy to give in to the natural impulse. Better to cut things short.

If you’re disappointed or offended, it doesn’t show. You look at your watch, a white face, with black roman numerals. Analog in a digital world. For a technology expert, a man who owns a cybersecurity firm, you haven’t even once looked at a phone.

“Where do you live?” you ask. “Right around the corner actually.”

“Can I walk you home?” You lift your palms, maybe reading my expression. “That’s it.”

I nod. “Sure.”

Outside, you offer your arm and I loop mine through. It’s funny and antiquated, but totally comfortable to stroll through the pretty tree-lined Brooklyn streets arm in arm like this. Your warmth, your strength. It’s magnetic. I feel something I haven’t felt in a long time. We walk in silence, pressing close. Finally, we get to my brownstone.

You look up at it, then to me. “All yours?”

I nod, a little embarrassed. I bought it when it was a total wreck and have been fixing it up for years. But, yeah, it’s a pretty big deal to have a place like this here.

“I thought you said you were a writer.” Everyone knows that writers are usually broke.

“I just got lucky with this place.”

Your smile is easy and knowing, no judgment. “There are a lot of layers to you, Wren Greenwood, that’s what I’m getting.”

That’s very true.

“There are a lot of layers to all of us, Adam Harper.”

You stare off into the middle distance for a moment, then back to me. “So—look.”

Ah, here it is. The brush-off. I knew he was too good to be true. “I’m not great at playing games.” You run a hand through your hair; in the glow from the streetlight, it sheens blue like blackbird feathers. I’ve already picked up that this is something you do when you feel uncomfortable.

You clear your throat and I stay quiet. You go on: “I like you. And I don’t want to have some soulless Torch hookup tonight.” Okay. Wow. Not what I was expecting. Again, I opt for silence, my default setting.

“So, can I take you to dinner tomorrow?” You glance at your watch again. “Well, tonight I guess?”

Somewhere down the street there’s a swell of piano music coming from one of the other brownstones. I hear this often, and it never fails to give the night a magical quality. The air is cool, though tomorrow is supposed to be a scorcher. Global weirding, go figure.

Jax would tell me to say I had to check my schedule. But Robin would tell me to be myself.

“I’d love to,” I say, not into games either. “Where and when?” “I’ll pick you up here at seven?”

I nod. “Perfect.”

You start to back away, hands in pockets, and I can’t stop smiling.

“Good night, Wren Greenwood.” “Good night, Adam Harper.”

Finally you turn and walk briskly away. Then, you’re gone around the corner.

Torch. It is shallow and soulless, a poor facsimile for human connection. But maybe there’s something to it after all.

I walk up the stone steps and let myself in with my electronic keypad, step into the silence of the home I have made, locking the door behind me. The air still smells of the soup I cooked earlier. It’s always a relief to return to the nest. For me, there’s a tension to all encounters, even the good ones.

The truth is that I haven’t really been with anyone seriously since college, and that was an embarrassingly long time ago. Let’s just say I have intimacy issues, trust issues.

Maybe I should have said what I was thinking: I like you, too, Adam.

On the other hand, we don’t know each other at all and maybe that’s how you end all your dates, easing the parting by scheduling the next encounter, one that will never happen.

Maybe, Adam, you won’t show up tomorrow and I’ll never see you again.

So it is with the modern dating ritual. Could go either way.

two

“So…hot or not?”

When I come downstairs the next morning, Jax is already in my kitchen, making coffee. I didn’t sleep well, my slumber plagued as ever by vivid dreams, mostly bad. I’m not surprised to see her. She has the door code and I heard her come in.

From the look of her, inky curls wrangled into a tight plait, dark skin flushed, T-shirt damp, she ran from her place in Chelsea. She’s a super miler, runs like a fiend—inside on machines, or outside through the city, over bridges to outer boroughs. She runs like something’s chasing her, fast and powerful, never, and I mean never, tiring. On the rare occasion I join her, she leaves me gasping in her dust.

“Hot?” I venture, slipping onto a stool at the island.

The kitchen is a work in progress, original appliances on their last legs, walls unpainted, light bulbs hanging from the ceiling waiting for their fixtures, cabinets in the middle of being refaced—doors gone, stain stripped. The guy I had working on the cabinetry has mysteriously disappeared; it’s been two weeks. Just a text: Hey, got called to another job. Be back to you soon.

Will he come back? There’s no way to know. It’s possible I’ve

been ghosted by an extremely talented and bizarrely cheap but massively unreliable carpenter.

Amid the ruin, a brand-new gleaming espresso machine and milk frother hum and hiss. Let it not be said that I don’t have my priorities straight.

“An answer should not sound like a question,” says Jax, in response to my uncertain statement.

She sounds just like her mother, Miranda, who over the last eight years has become like my surrogate mother. But I know better than to say so. Jax pours almond milk in the frother and presses the button. The aroma of espresso, already in cups, wafts on the air.

“It’s a reductive question,” I say. “Hot or not? What are we— internet trolls?”

She pins me with her stunning green-hazel eyes. Jamaican mother, British father, Jax always says that she’s a true Ameri- can girl. Her ancestors hail from all over the world, but she is Brooklyn born and raised. So, New Yorker first, everything else second.

“He’s not still here, is he?”

She looks past me, her gaze traveling down the hall toward the stairs.

I shake my head, gratefully take the cup of coffee she hands me over the quartz countertop that sits, not properly secured yet, atop the unfinished island. “I told you I wasn’t going to do that again. No more Torch hookups.”

She shrugs and lifts her eyebrows, as if this is some unreasonable assertion, takes a sip of her coffee. “So what happened?”

What did happen? Something. I felt something, which I wouldn’t have said about my last encounters.

I woke up thinking about you, Adam, wondering if we are really having dinner tonight.

“Nothing,” I tell her. “We talked, we walked. It was—nice.” “Did you take a picture?”

I laugh at this. Jax lives online. It’s 8:00 a.m. and she’s probably already posted on Instagram about her morning run. I keep a much lower profile. “He wasn’t the selfie type.”

“Okay,” she says, drawing out the syllables. “What type was he?”

“I guess the type I’m going to see again. He asked me to dinner tonight.”

Raising her eyebrows again, this time in surprise, she slides into the seat next to me and we drink the strong coffee in companionable silence for a moment. She’s scrolling on her phone. Glancing over, I see that she’s pulled up your profile.

The picture is unflattering. You’re better looking in person.

Her frown tells me that she doesn’t approve of you. “What about the other guy?” she asks.

“Which one?”

“The literary one. You said he was nice, you know— talented.” She laughs, moving her shoulders, mock sexy.

I find myself staring at her; I’m often a bit enthralled by her beauty—her high cheekbones, gleaming eyes, full lips. My friend doesn’t think she’s beautiful, but she is.

“Drew,” I say, remembering him—nice body, thick head of dark hair, bedroom eyes. I don’t remember thinking he was talented. Our night together was serviceable at best. “He didn’t call.”

She tips her head to the side, considers this. “You didn’t call him either.”

“Exactly. There was nothing there,” I say, thinking that will be the end of it. But she’s still watching me. “What?”

Jax looks for a long moment at your picture, tugging at her braid. “This guy. He just seems—too serious. I just want you to—you know—have fun.”

As far as my friend is concerned, Torch hookups need to be light and easy—nightclub dates, weekend trips to Miami Beach, champagne brunches that end back in bed. That’s her. Not me.

She looks at me like she wants to go on, but then presses her mouth shut.

“What?” Instantly defensive in the way that you can only be with people who know you too well.

She lifts her palms. “I’m just saying. Don’t get hooked into one guy, date around a little.”

Date around a little. She uses the app as a catalog of potential hookups. I’m not sure she’s seen the same guy more than twice. This is the way of it. Swipe left. Swipe right. The pool is big and shallow; if reality doesn’t measure up to socials (and when does it?)—block, unfriend, delete, move on.

The idea—her idea—was for me to get out there. Stop working so hard. Live a little, let loose.

“What are you worried about?” I bump her with my shoulder; she reaches for my hand and gives it a squeeze. “He probably won’t even call. I’ll never see him again.”

“Hmm,” she says. “What about this guy?”

She holds up a picture, an extremely fit man with a goatee and slicked-back hair flexes his muscles and stares suggestively at the camera. We both break out laughing.

“Uh,” I say. “Pass.”

There’s a tapping at the window over the sink, and I look up to see a blackbird there. He gazes inside, inquiring. I’ve been leaving seeds for him. There’s a postage-stamp-sized backyard behind my town house and I’ve filled it with plants; the blackbird has made a nest I think in the gutter over the back door. I walk over to the sink and look out at him. His body gleams blue in the morning light.

And just like that, I’m back there.

My father’s house. Big and rambling, run-down and with a list of problems we didn’t have the money to fix. Isolated on a huge tract of land that had been in his family for generations. The house where he grew up, and where he moved our family when I was ten for reasons I couldn’t understand at the time.

I put my fingers on the glass, and remember the foggy window in the old kitchen, the warm, nutty scent of oatmeal on the stove, my mother humming softly, my brother Jay sulking, angry about something—everything. There was a blackbird that visited that window, too, attracted by seeds my mother left. Birds are the messengers of the universe, she used to say. They sing its song.

“Wren.”

I startle back to the moment, to Jax. “Earth to Wren. Where did you go?”

Home, I think. I went home.

“My point is,” Jax goes on. “Just take it slow. See him again if you want. But date a few other people. Have some fun, you know. Things don’t always have to be—so heavy, so serious.”

She’s talking about my work, our work, but more than that.

She’s talking about me.

I watch the blackbird peck at his seed. He cocks his head at me, then flaps away into the gunmetal-gray sky.

Order the Book

She met him through a dating app. An intriguing picture on a screen, a date at a downtown bar. What she thought might be just a quick hookup quickly became much more. She fell for him—hard. It happens sometimes, a powerful connection with a perfect stranger takes you by surprise. Could it be love?

But then, just as things were getting real, he stood her up. Then he disappeared—profiles deleted, phone disconnected. She was ghosted.

Maybe it was her fault. She shared too much, too fast. But isn't that always what women think—that they're the ones to blame? Soon she learns there were others. Girls who thought they were in love. Girls who later went missing. She had been looking for a connection, but now she's looking for answers. Chasing a digital trail into his dark past—and hers—she finds herself on a dangerous hunt. And she's not sure whether she's the predator—or the prey.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

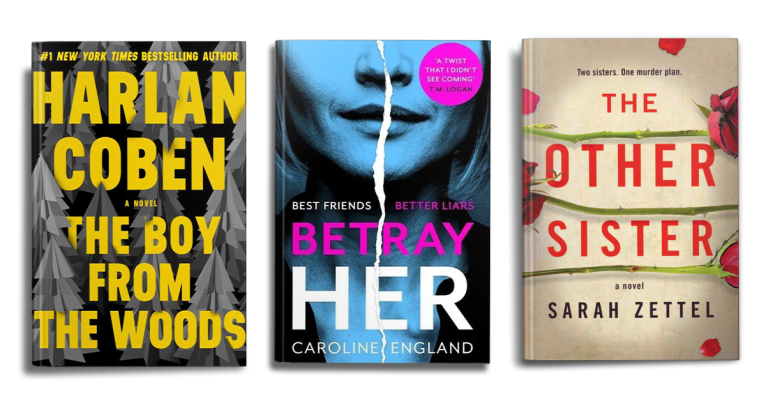

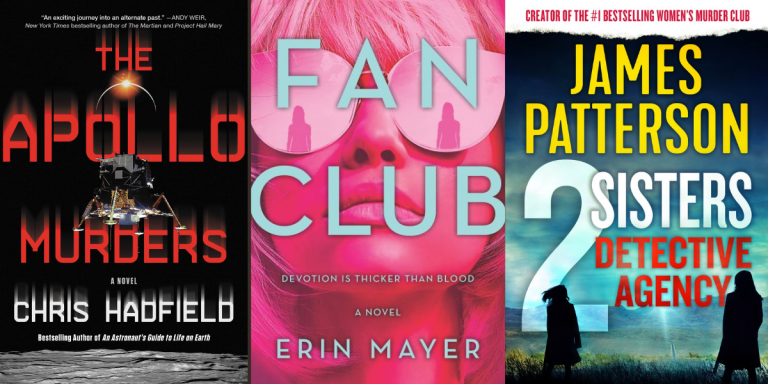

What to Read Next