Read The Excerpt: Chaos by Tom O’Neill

Vincent Bugliosi was on another tirade.

“Nothing could be worse than accusing a prosecutor of doing what you’re implying that I did in this case,” he barked at me. “It’s extremely, extremely defamatory.”

It was a sunny day in February 2006, and we were in the kitchen of his Pasadena home. The place was cozy, with floral patterns, overstuffed furniture, and—literally—a white picket fence out front, all belying the hostility erupting within its walls. Bugliosi wanted to sue me. It would be, he soon warned, “a hundred-million-dollar libel lawsuit,” and “one of the biggest lawsuits ever in the true-crime genre.” If I refused to soft-pedal my reporting on him, I’d be powerless to stop it.

“I think we should view ourselves as adversaries,” he’d tell me later.

Vince—I was on a first-name basis with him, as I guess adversaries must be—was a master orator, and this was one of his trademark perorations. Our interview that day dragged on for more than six hours, and he did most of the talking, holding forth as expertly as he had when he prosecuted the Charles Manson trial more than thirty-five years before. Seventy-one and in shirtsleeves, Vince still cut an imposing figure, hectoring me over a Formica table strewn with legal pads, notes, tape recorders, pens, and a stack of books—all written by him. Wiry and spry, his eyes a steely blue, he would sit down only to leap up again and point his finger in my face.

Riffling through the pages of one of his yellow legal pads, he read from some remarks he’d prepared. “I’m a decent guy, Tom, and I’m going to educate you a little about just how decent Vince Bugliosi is.”

And so he did—reciting a prewritten “opening statement” that lasted for forty-five minutes. He insisted on beginning this way. He’d dragooned his wife, Gail, into serving as a witness for the proceedings, just in case I’d try to misrepresent him. Essentially, he’d turned his kitchen into a courtroom. And in a courtroom, he was in his element.

Bugliosi had made his name with the Manson trial, captivating the nation with stories of murderous hippies, brainwashing, race wars, and acid trips gone awry. Vince was sure to remind me, early and often, that he’d written three bestselling books, including Helter Skelter, his account of the Manson murders and their aftermath, which became the most popular true-crime book ever. If he seemed a little keyed up that day, well, so was I. My task was to press him on some of his conduct in the Manson trial. There are big holes in Helter Skelter: contradictions, omissions, discrepancies with police reports. The book amounts to an official narrative that few have ever thought to question. But I’d found troves of documents—many of them unexamined for decades, and never before reported on—that entangled Vince and a host of other major players, like Manson’s parole officer, his friends in Hollywood, the cops and lawyers and researchers and medical professionals surrounding him. Among many other things, I had evidence in Vince’s own handwriting that one of his lead witnesses had lied under oath.

I sometimes wonder if Vince could see what a bundle of nerves I was that day. I’m not a churchgoing person, but I’d gone to church that morning and said a little prayer. My mom always told me I should pray when I need help, and that day I needed all the help I could get. I hoped that my interview with Vince would mark a turning point in my seven years of intensive reporting on the Manson murders. I’d interviewed more than a thousand people by then. My work had left me, at various points, broke, depressed, and terrified that I was becoming one of “those people”: an obsessive, a conspiracy theorist, a lunatic. I’d let friendships fall away. My family had worried about my sanity. Manson himself had harangued me from prison. I’d faced multiple threats on my life. I don’t consider myself credulous, but I’d discovered things I thought impossible about the Manson murders and California in the sixties—things that reek of duplicity and cover-up, implicating police departments up and down the state. Plus, the courts. Plus—though I have to take a deep breath before I let myself say it—the CIA.

If I could get Bugliosi to admit any wrongdoing, or even to let a stray detail slip, I could finally start to unravel dozens of the other strands of my reporting. Maybe soon I could get my life back, whatever that might look like. At the very least, I could know that I’d done all I could to get to the bottom of this seemingly endless hole.

Sitting in his kitchen, though, and watching the hours wear on as Vince defended and fortified every point he made, my heart sank. He was stonewalling me. I could hardly get a word in edgewise.

“It’s a tribute to your research,” he told me. “You found something that I did not find.” In the closest thing I got to a concession, he said, “Some things may have gotten past me.” But, he added, “I would never in a trillion years do what you’re suggesting. Okay? Never. My whole history would be opposed to that. And number two, Tom, even if I had the thought that you’re suggesting”—of suborning perjury—“it goes nowhere. It’s preposterous. It’s, it’s silly… Who cares? It means nothing!”

Who cares? I’ve asked myself that a lot over the years. Was it worth investing so much of my time and energy in these, some of the most well-known, worn-out crimes in American history? How did I end up falling into this, anyway? I remember glancing over at Gail, Vince’s wife, during his long, stentorian “opening statement.” She was leaning against the counter looking exhausted, her eyelids drooping. Eventually, she excused herself to go upstairs and lie down. She must’ve heard it all a thousand times before, his scripted lines, his self-aggrandizement. When I’m down on myself, I imagine everyone feels like Gail did that day. Oh, no, not the Manson murders, again. We’ve been through this. We’ve processed this. We know everything there is to know. Don’t drag us back into this story.

I was almost heartened, then, to see that Vince was so anxious. That’s what kept me going, knowing that I’d gotten under his skin. Why would he be so committed to stopping this? And if what I’d discovered was really “nothing,” why had so many of his former colleagues told me otherwise?

Another one of my sources had tipped off Vince about my reporting, giving him the ludicrous idea that I believed he’d framed Manson. That was dead wrong. I’ve never been a Manson apologist. I think he was every bit as evil as the media made him out to be. But it is true that Stephen Kay—Vince’s coprosecutor on the case, and no friend of his—had been shocked by the notes I’d found in Vince’s handwriting, telling me they could be enough to overturn all the verdicts against Manson and the Family. That was never my goal, though. I just wanted to find out what really happened. “I don’t know what to believe now,” Kay told me. “If he [Vince] changed this, what else did he change?”

I wanted to know the same thing, but Vince always found a way to change the subject. “Where does it go?” he kept asking. “What’s the point?” The point, as I saw it, was that an act of perjury called the whole motive for the murders into question. Vince was too busy patronizing me about my motives to take that into consideration. How could I dare insinuate that he’d done something wrong? How could I live with myself if I tarnished his sterling reputation? He liked to bring up “the Man in the Mirror,” as if he, and not Michael Jackson, had popularized the phrase. “You cannot get away,” Vince said, “you cannot get away from him!” I tried to steer the conversation back to Manson, but Vince was having none of it. He wanted to recite some “testimonials” about his good character, to “read them into the record.”

Both of us had showed up that day with two tape recorders—I was as scrupulous as he was, and neither of us wanted to risk having an incomplete account of the conversation. Over and over, whenever the intensity mounted and Vince had something sensitive to say, he would demand that we go off the record, meaning each of us had to shut off two machines, sometimes just for a few seconds, only to turn them all back on again. Often he’d forget one of his, and I’d have to say, “Vince, you didn’t turn it off.”

Off the record, he’d lash into me again, his eyes piercing under that silver crescent of hair. “If you do the book and it’s legally defamatory, you have to realize one thing,” he said. “You have to realize I have no choice. I have to sue you.”

By the time I left his house, I had a headache from all his shouting, and the sun had set behind the San Gabriel Mountains. Gail had never bothered to come downstairs again. Outside, before I got to my car, Vince grabbed my arm and reminded me that a blurb from him could boost the sales of my book—and he’d be happy to offer one, provided the manuscript passed muster with him. “That’s not a quid-pro-quo offer,” he added. But it seemed like one to me.

Driving away, I felt despondent. I’d just gone toe-to-toe with one of the most famous prosecutors and true-crime authors in the world. Of course I hadn’t broken him. I knew I wasn’t alone, either. Other reporters had warned me that Vince could be ferocious. One of them, Mary Neiswender of the Long Beach Press Telegram and Independent, told me that Vince had threatened her back in the eighties, when she was preparing an exposé on him. He knew where her kids went to school, “and it would be very easy to plant narcotics in their lockers.” Actually, I didn’t even need other sources—Vince himself had told me mere minutes before that he had no compunction about hurting people to “exact justice or get revenge.”

As it turned out, my reprieve was short-lived. I arrived at my home in Venice Beach to find that he’d already left me a message, wanting to talk about “a couple of follow-up things.” I called him back and we talked for another few hours. The next day, we had another phone call—then another, then another. When he saw that I wouldn’t back down, Vince only grew more exasperated.

“If you vaguely imply to your readers that I somehow concealed evidence from the Manson jury,” he told me on the phone, “whether you believe it or not, the only thing you’re going to be accomplishing is jeopardizing your financial future and that of your publisher.” Demanding an apology, he assured me that I was treading “in dangerous waters”: “It’s possible the next time we see each other I’ll be cross-examining you on the witness stand.”

Fortunately, that never happened. The next time I saw Vince, it was June 2011, and he was striding past me in an auditorium at the Santa Monica Library, where he was giving a talk. He’d noticed me—his adversary—in the crowd and paused as he made his way forward.

“Are you Tom O’Neill?”

“Yes. Hi, Vince.”

“Why are you so happy?”

I must’ve been smiling out of nervousness. “I’m happy to see you,” I said.

Studying me a bit, he asked, “Did you do something to your hair?”

“No.”

“It looks different.” He kept walking. And that was it. We never spoke again. Vince died in 2015. Sometimes I wish he were alive to read what follows, even if he’d try to sue me over it. I feel foolish for having expected to get firm answers from him. I replay the scenario in my head, figuring out where I could’ve caught him in a lie, where I should’ve pressed him harder, how I might’ve parried his counterattacks. I really thought that, with enough tenacity, I could get to the truth under all this. Now, most of the people who had the full story, including Manson himself, have died, and the questions I had then have continued to consume me for almost twenty years. But I’m certain of one thing: much of what we accept as fact is fiction.

1

The Crime of the Century

Two Decades Overdue

My life took a sharp left-hand turn on March 21, 1999, the day after my fortieth birthday—the day all this started. I was in bed with a hangover, as I’d been after countless birthdays before, and I felt an acute burst of self-loathing. I was a freelance journalist who hadn’t worked in four months. I’d fallen into journalism almost by accident. For years I’d driven a horse and carriage on the night shift at Central Park, and over time, my unsolicited submissions to magazines like New York had led to bigger and better assignments. While I was happy, now, to be living in Venice Beach and making a living as a writer, I missed New York, and mine was still a precarious existence. My friends had obligations: they’d started families, they worked long hours in busy offices, they led full lives. Even though my youth was behind me, I was so untethered that I could sleep into the afternoon—actually, I couldn’t afford to do much else at that point. I felt like a mess. When the phone rang, I had to make a real effort just to pick it up.

It was Leslie Van Buskirk, my former editor from Us magazine, now at Premiere, with an assignment. The thirtieth anniversary of the Manson murders was coming up, and she wanted a reported piece about the aftershocks in Hollywood. So many years later, Manson’s name still served as a kind of shorthand for a very American form of brutal violence, the kind that erupts seemingly from nowhere and confirms the nation’s darkest fears about itself. The crimes still held great sway over the public imagination, my editor said. What was it that made Manson so special? Why had he and the Family lingered in the cultural conversation when other, even more macabre murders had faded from memory? Premiere was a film magazine, so my editor wanted me to talk to Hollywood’s old guard, the generation that had found itself in disturbing proximity to Manson, and to find out how they felt with three decades of perspective. It was a loose concept; Leslie trusted me to find a good direction for it, and to shape it into something unexpected.

I almost said no. I’d never been particularly interested in the Manson murders. I was ten years old when they happened, growing up in Philadelphia, and though my brother swears up and down that he remembers me keeping a scrapbook about the crimes, I can’t recall how they affected me in the slightest. If anything, I thought I was one of the few people on the planet who’d never read Helter Skelter. Like an overplayed song or an iconic movie, Manson held little interest to me precisely because he was ubiquitous. The murders he’d ordered were often discussed as “the crime of the century,” and crimes of the century tend to be pretty well picked over.

But I needed the job, and I trusted Leslie’s judgment. We’d worked together on a number of stories at Us—it was a monthly magazine then, not a weekly tabloid—and a piece like this, pitch-black, would be a welcome departure from my routine as an entertainment writer, which called for a lot of sit-down meetings with movie stars in their cushy Hollywood Hills homes, where they’d trot out lines about brave career choices and the need for privacy. That’s not to say the work was without its twists and turns. I’d gotten in a shouting match with Tom Cruise about Scientology; Gary Shandling had somehow found a way to abandon me during an interview in his own home; and I’d pissed off Alec Baldwin, but who hasn’t?

I had some chops, in other words, but not much in the way of investigative bona fides. For a recent story about an unsolved murder, I’d chased down some great leads, but because my case was mostly circumstantial, the magazine sensibly decided to play it safe, and the piece came out toothless.

This time, I thought, I could do better. In fact, through the fog of my hangover, I remember thinking: this will be easy. I agreed to file five thousand words in three months. Afterward, I thought, maybe I could move back to New York.

Twenty years later, the piece isn’t finished, the magazine no longer exists, and I’m still in L.A.

“A Picture Puzzle”

Before I interviewed anyone, I read Helter Skelter. I saw what all the fuss was about: it was a forceful, absorbing book, with disquieting details I’d never heard before. In their infamy, the murders had always seemed to exist in a vacuum. And yet, reading Bugliosi’s account, what had seemed flat and played out was full of intrigue.

I made notes and lists of potential interviews, trying to find an angle that hadn’t been worked over. Toward the beginning of the book, Bugliosi chides anyone who believes that solving murders is easy:

In literature a murder scene is often likened to a picture puzzle. If one is patient and keeps trying, eventually all the pieces will fit into place. Veteran policemen know otherwise… Even after a solution emerges—if one does—there will be leftover pieces, evidence that just doesn’t fit. And some pieces will always be missing.

He was right, and yet I wondered about the “leftover pieces” in this case. In Bugliosi’s telling, there didn’t seem to be too many. His picture puzzle was eerily complete.

That sense of certitude contributed to my feeling that the media had exhausted the murders. The thought of them could exhaust me, too. Bugliosi describes Manson as “a metaphor for evil,” a stand-in for “the dark and malignant side of humanity.” When I summoned Manson in my mind, I saw that evil: the maniacal gleam in his eye, the swastika carved into his forehead. I saw the story we tell ourselves about the end of the sixties. The souring of the hippie dream; the death throes of the counterculture; the lurid, Dionysian undercurrents of Los Angeles, with its confluence of money, sex, and celebrity.

Because we all know that story, it’s hard to discuss the Manson murders in a way that captures their grim power. The bare facts, learned and digested almost by rote, feel evacuated of meaning; the voltage that shot through America has been reduced to a mild jolt, a series of concise Wikipedia entries and popular photographs. In the way that historical events do, it all feels somehow remote, settled.

But it’s critical to let yourself feel that shock, which begins to return as the details accumulate. This isn’t just history. It’s what Bugliosi called, in his opening statement at the trial, “a passion for violent death.” Despite the common conception, the murders are still shrouded in mystery, down to some of their most basic details. There are at least four versions of what happened, each with its own account of who stabbed whom with which knives, who said what, who was standing where. Statements have been exaggerated, recanted, or modified. Autopsy reports don’t always square with trial testimony; the killers have not always agreed on who did the killing. Obsessives continue to litigate the smallest discrepancies in the crime scenes: the handles of weapons, the locations of blood splatters, the coroner’s official times of death. Even if you could settle those scores, you’re still left with the big question—Why did any of this happen at all?

Something to Shock the World

August 8, 1969. The front page of that morning’s Los Angeles Times described an ordinary day in the city. Central Receiving Hospital had failed to save the life of a wounded policeman. The legislature had passed a new budget for schools, and scientists were optimistic that Mars’s south polar cap could be hospitable to alien life. In London, the Beatles had been photographed crossing the street outside their studio, a shot that would become the cover of Abbey Road. Walter Cronkite led the CBS Evening News with a story about the devaluation of the franc.

The space race was in full swing, and Americans were dreaming, sometimes with a touch of trepidation, about the science-fictional future. Less than three weeks earlier, NASA had put the first man on the moon, an awe-inspiring testament to technological ingenuity. Conversely, the number one song in the country was Zager and Evans’s “In the Year 2525,” which imagined a dystopian future where you “ain’t gonna need to tell the truth, tell no lies / Everything you think, do, and say / Is in the pill you took today.” It would prove to be a more trenchant observation about the present moment than anyone would’ve thought.

Late that night at the Spahn Movie Ranch, a man and three women got in a beat-up yellow 1959 Ford and headed toward Beverly Hills. A ranch hand heard one of the women say, “We’re going to get some fucking pigs!”

The woman was Susan “Sadie” Atkins, twenty-one, who’d grown up mostly in San Jose. The daughter of two alcoholics, she’d been in her church choir and the glee club, and said that her brother and his friends would often molest her. She had dropped out of high school and moved to San Francisco, where she’d worked as a topless dancer and gotten into LSD. “My family kept telling me, ‘You’re going downhill, you’re going downhill, you’re going downhill,’” she would say later. “So I just went downhill. I went all the way down to the bottom.”

Huddled beside her in the back of the car—they’d torn out the seats to accommodate more food from the Dumpster dives they often went on—was Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel. Twenty-one, from Inglewood, Krenwinkel had developed a hormone problem as a kid, leading her to overeat and fear that she was ugly and unwanted. As a teen, she got into drugs and started to drink heavily. One day in 1967, she’d left her car in a parking lot, failed to collect the two paychecks from her job at an insurance company, and disappeared.

In the passenger seat was Linda Kasabian, twenty, from New Hampshire. She’d played basketball in high school, but she dropped out to get married; the union lasted less than six months. Not long after, in Boston, she was arrested in a narcotics bust. By the spring of 1968, she’d remarried, had a kid, and moved to Los Angeles. She sometimes introduced herself as “Yana the witch.”

And at the wheel was Charles “Tex” Watson, twenty-three and six foot three, from east Texas. Watson had been a Boy Scout and the captain of his high school football team; he sometimes helped his dad, who ran a gas station and grocery store. At North Texas State University, he’d joined a fraternity and started getting stoned. Soon he dropped out, moved to California, and got a job as a wig salesman. One day he’d picked up a hitchhiker who turned out to be Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys—a chance occurrence that changed both of their lives forever.

That night in the Ford, all four were dressed in black from head to toe. None of them had a history of violence. They were part of a hippie commune that called itself the Family. Living in isolation at the Spahn Ranch—whose mountainous five hundred acres and film sets had once provided dramatic backdrops for Western-themed movies and TV shows—the Family had assembled a New Age bricolage of environmentalism, anti-establishment politics, free love, and apocalyptic Christianity, rounded out with a vehement rejection of conventional morality. More than anything, they lived according to the whims of their leader, the thirty-four-year-old Charles Milles Manson, who had commanded them to take their trip that night.

The four arrived at 10050 Cielo Drive, where the actress Sharon Tate lived with her husband, the filmmaker Roman Polanski. He was away in London at the time, scouting locations for The Day of the Dolphin, a movie in which a dolphin is trained to assassinate the president of the United States.

The drive to Cielo would’ve taken about forty minutes. It was just after midnight when they arrived. Benedict Canyon was quiet, seemingly worlds away from the hustle and sprawl of Los Angeles. The house, built in 1942, had belonged to a French actress, who’d modeled it on the Norman country estates of her youth. A long, low rambler at the end of a cul-de-sac, invisible from the street, it sat on three acres of bucolic, isolated land. Nestled against a hillside on a bluff, it afforded views of Los Angeles glittering to the east and Bel Air’s fulsome estates unfurling to the west. On a clear day, you could see straight to the Pacific, ten miles out.

Watson scaled a pole to sever the phone lines to the house. He’d been here before, and he knew where to find them right away. There was an electric gate leading to the driveway, but instead of activating it, the four elected to jump over an embankment and drop onto the main property. All of them were carrying buck knives; Watson also had a .22 Buntline revolver. Kasabian remained on the outskirts, keeping watch. The other three crept up the hill toward the secluded estate.

At the top of the driveway they found Steven Parent, an eighteen-year-old who’d been visiting the caretaker in the guesthouse to sell him a clock radio. He was sitting in his dad’s white Rambler, having already rolled his window down to activate the gate control. Watson approached the driver’s side and pointed the revolver at his face. “Please don’t hurt me, I won’t say anything!” Parent screamed, raising his arm to protect himself. Watson slashed his left hand with the knife, slicing through the strap of his wristwatch. Then he shot Parent four times, in his arm, his left cheek, and twice in the chest. Parent died instantly, his blood beginning to pool in the car.

Those four shots rang out through Benedict Canyon, but no one in the house at 10050 Cielo seemed to hear them. It was a rustic home of stone and wood, its clapboard siding often described, in the many newspaper stories soon to follow, as tomato red. Beside the long front porch, a winding flagstone path led past a wishing well with stone doves and squirrels perched on its lip. There was a pool in the back and a modest guesthouse. The yard had low hedges, immense pines, and welcoming beds of daisies and marigolds. A white Dutch door opened into the living room, where a stone fireplace, beamed ceilings, and a loft with a redwood ladder provided a warm ambience.

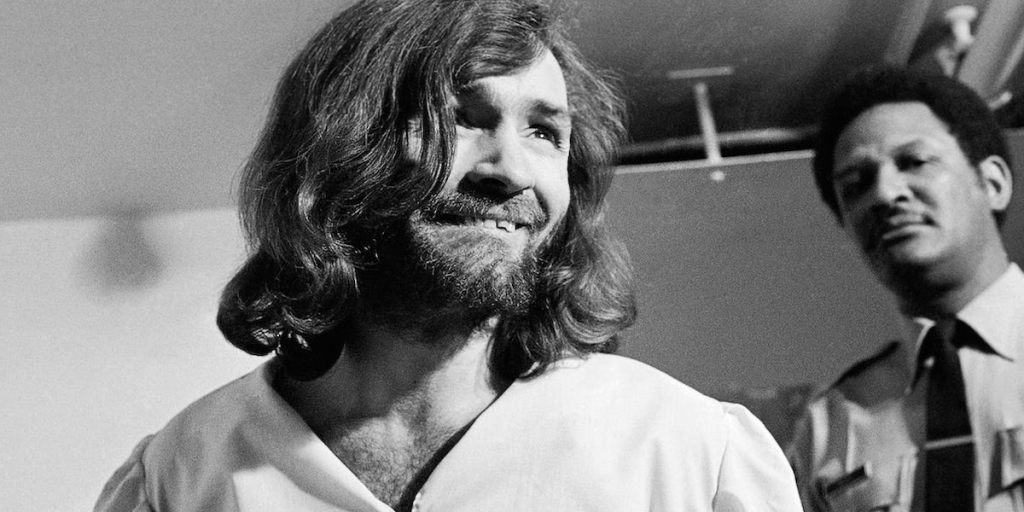

Over two grim nights in Los Angeles, the young followers of Charles Manson murdered seven people, including the actress Sharon Tate, then eight months pregnant. With no mercy and seemingly no motive, the Manson Family followed their leader's every order—their crimes lit a flame of paranoia across the nation, spelling the end of the sixties. Manson became one of history's most infamous criminals, his name forever attached to an era when charlatans mixed with prodigies, free love was as possible as brainwashing, and utopia—or dystopia—was just an acid trip away.

Twenty years ago, when journalist Tom O'Neill was reporting a magazine piece about the murders, he worried there was nothing new to say. Then he unearthed shocking evidence of a cover-up behind the "official" story, including police carelessness, legal misconduct, and potential surveillance by intelligence agents. When a tense interview with Vincent Buglios—prosecutor of the Manson Family and author of Helter Skelter—turned a friendly source into a nemesis, O'Neill knew he was onto something. But every discovery brought more questions.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use