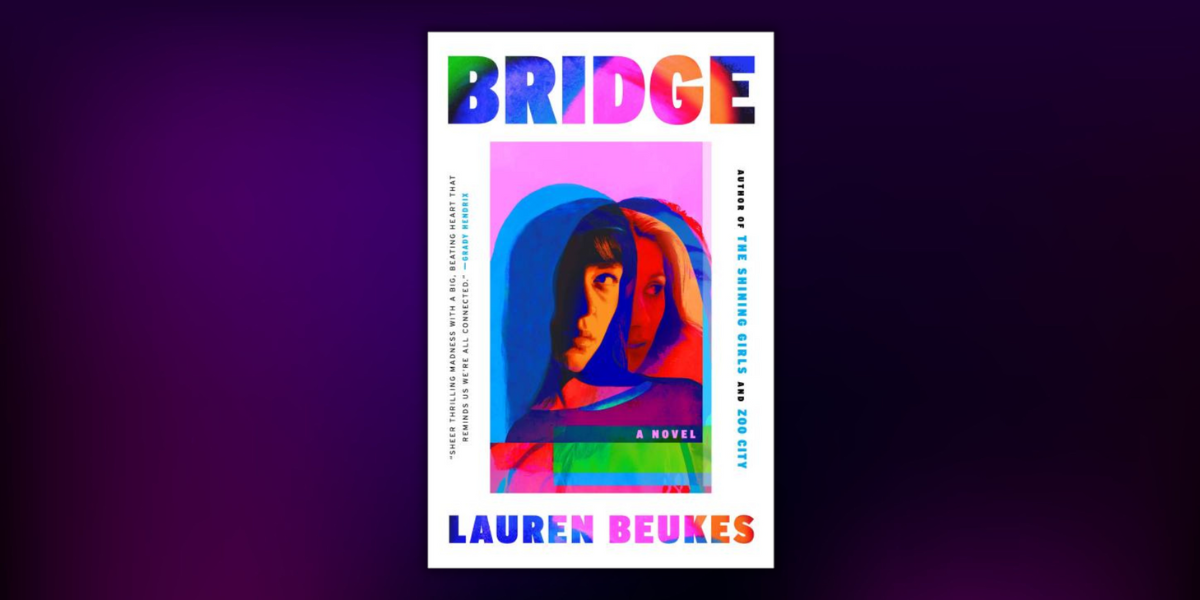

Read the Excerpt: Bridge by Lauren Beukes

BRIDGE

BRIDGE

Portrait of a Kidnapping

April 2006

On the long stretches of highway, her mom lets her sit up front next to her, although Bridge has to slouch down when they pass a police car, because they are being a little bit naughty and seven‑year‑olds are supposed to sit in the back. The road is a dark ribbon through the trees, like in the story about the little girl escaping from the witch Baba Yaga and her chicken‑footed house.

You don’t have to think like that, Mom says. There’s no one chasing us. But her eyes flick to the mirror again and again, and when she has to pull over at the gas station to take her pills so she doesn’t get fits, she sits waiting in the car, watching the parking lot, before she goes inside, and Bridge can’t stay behind because I need you to pick the best doughnuts.

“Isn’t this nice, the two of us getting away? Surprise vacation!”

“I miss Bear,” Bridge says. “And also Daddy.” Her dad is a very busy guy. And motels don’t allow galumphing Labra‑ dors. But it doesn’t feel like a vacation. It’s not very fun. And she thinks maybe this is her fault because of what happened at her mom’s lab, which isn’t really her lab, but the professor lets her come there to do her studies and sneak Bridge in. It’s boring there. She is not allowed to climb the high wooden shelves or roll down the corridors on one of the wheelie chairs or play with the plush toy of a brown worm with a knot tied in its tail that sits on top of the filing cabinet, and I’m not sure how your dad would feel about you playing with Ebola. Bridge does know. He would not approve.

Mostly, she sits at Mom’s desk reading comic books or doing her puzzle, which has five hundred pieces, but she lost four of them, so there is a hole in the unicorn’s butt like a tiger took a bite out of it. But one day she did something bad while Mom was busy talking to the other brain scientists. So much talking! She didn’t mean to. The rats were so cute and she just wanted to let them out so she could play with them, and she didn’t even really manage to open the door to any of their cages, which aren’t really cages but kind of glass nests. Mom got in so much trouble with her boss and with Daddy.

She shouldn’t have been there unsupervised, her dad said, talking through his teeth, and What were you thinking and This is why — and he caught her looking and pulled Mom into their bedroom by the elbow and slammed the door and their voices were soft and spitty like cobras and then suddenly loud and high like yappy dogs, and Bridge could hear the words What do you expect me to do and I can’t live like this and Ungrateful is what you are, I didn’t even want—and Bridge just turned up the TV because it was her fault they were fighting because of the rats. So maybe it’s also her fault they need some girl time now, her and Mom.

They find a youth hostel near Bourbon Street, which

smells gross on Sunday morning, like wet garbage and sick. Jo does card tricks for the backpackers from South Africa and New Zealand and Ireland and tells them how she used to live here, in New Orleans, but not in the tourist part, when she was their age, or younger, actually, fourteen when she ran away from home—and for the first time, Bridge thinks: Oh, is that what we’re doing?

They drive all around the city, past old‑fashioned houses and under twists of highway near the stadium, past the cemetery with white marble tombs like a Lego city for ghosts. They visit a broken house with graffiti and holes in the floor and Mom says this was her home when she was a runaway, but Bridge doesn’t want to go inside because it’s creepy and there are spiky thistles everywhere and what if the roof falls down?

They stop at restaurants and bookstores, Mom always asking around for people she used to know. Once a man followed them back to the car. Hey, pretty lady, I can help with that, maybe you can help me, know what I’m saying and Mom snarled, Fuck off, and that only made him mad, so they had to run and jump into the car, and he came after them and slapped the back windshield as they drove off.

Her mom says they’re trying to find a rabbit, but they find a witch instead, with curly hair and tattoos of stars and not scary like Baba Yaga. Her name is Mina and she knows her mom from back in the day, and Bridge is impressed at how she is grubby and glamorous at the same time in a short black dress and big army boots with the laces undone so she might trip at any moment.

She lives up a flight of rickety metal stairs in an old warehouse, and as she climbs, Bridge has to hold the railing really tight and not look down at the gaps where the sky shines through. Everything is in one room, the rumpled and crumpled bed and the kitchen, full of plants and glass bottles and things you might find washed up on the beach, old bones, and antlers and bits of coral, still pinky red, with skinny twisted fingers. There are string lights hanging from the ceiling and the skeleton of a huge bird with its wings spread wide and some of the feathers still attached, kinda ratty, but still determined to fly. She has dreams about that dead bird afterward, but she has a lot of weird dreams that year.

Mina and her mom talk and talk and talk and cry and Bridge gets bored and embarrassed. Then she must have dozed off on the couch, because it is evening and Mina is unlocking one of the display cases and lifting out something wrapped in a creamy cloth like an Egyptian mummy.

Mina keeps saying the rabbit is dead and, maybe that’s what it is, all wrapped in cloth—a dead baby bunny—also Mina doesn’t want to give the mummy to her mom, but her mom keeps saying she needs it. More than anything. Please.

And Mina says, I hope you know what you’re doing. And her mom says, I don’t have a choice.

BRIDGE

So Barve RN

This is not where Bridge is supposed to be. Story of her life. But here especially, standing on the threshold of her dead mother’s home — this most haunted of houses. Reality is not real, her mom used to say. Your perception is a lie your mind tells you. It’s only that Jo’s brain told her grander and more dangerous lies than most people’s—that the world was more than it was—and for a time after they got back from being on the run, Bridge believed it too.

“It’s not your fault,” her therapist, Monica, told her

repeatedly. She was a little kid, seven years old; her mom had a brain tumor that made her delusional, and she brought Bridge into her dreamworld for a little while. She was better afterward, didn’t mention it for years and years, but then she got sick again, and it all came rushing back. The absurd, desperate fantasy. And now she is dead.

This is a raw physical fact; incontrovertible.

This is real, like the cold metal of the key in her hand on this quiet street in Mount Scott–Arleta, the cicadas ratchet‑ ing in the trees, and the Grand Am’s engine clicking accompaniment. Dom drove it here all the way from Austin to help her, and it broke down only once. Or so they claim.

Dom is wearing a blue jumpsuit and puffy Day‑Glo sneakers—“Manual labor, but make it fashion,” they quipped when they picked her up this morning from that hateful anonymous apartment two blocks over from the OHSU Hospital in Marquam Hill.

By contrast, Bridge is wearing leggings and a black T‑shirt. Grief, but make it entropy. It’s been her uniform for the past few days, since her mom took a sharp, sudden downturn and she flew here, too late. Jo was in no state to even recognize her. You’re not my daughter. Chemo‑induced dementia, the doctor said, or the tumor pressing on her brain. Again. Jo was fifty‑one years old, but the cancer had been trying to kill her for almost forty years. Once, twice, third time’s the charm. Joke the pain away, she thinks.

Dom has brought supplies: cardboard boxes, folders,

labels, stickers, packing tape, groceries, a bottle of tequila — all the essentials needed to deal with your dead mother’s estate. And doesn’t that word estate imply a mansion in the countryside with secret passages for the servants and hidden treasures in the attic rather than this modest boho cottage, cycling distance to Everard University? Sure, her mom had sent her a cryptic e‑mail about “frozen assets,” adding that she’d provide further instructions when they next saw each other, but in the hospital she was too out of it to talk, and her lawyer didn’t know anything about it. Wouldn’t it be great if there was a secret inheritance: gold bullion, a lost Dora Maar portrait, or, ya know, answers, closure? All the things left unsaid.

I don’t know you.

She didn’t get to say goodbye, not properly, not in those circumstances, with Jo turned to face the curtain, her scrawny shoulders hitching, flinching away from Bridge when she tried to touch her, tried to tell her she loved her. The uncrossable gap between them stretching wider.

I want to go home.

Bridge thought she only had to wait it out, that it would run its course like Jo’s epileptic seizures, and her mother would emerge on the other side, and they could talk. But she didn’t. And now all that’s left of Jo is cremains in a plastic bag inside a wooden box shoved in a cheap wheelie suitcase.

Dom is mucking about, holding a blue plastic label printer like a gun and sweeping it across the neat houses of Portland, with their neat lawns and their neat curtains and neat lives inside, acting as if they are in an over‑the‑top action movie with assassins ready to descend instead of in another chapter of Bridget Kittinger‑Harris’s so‑far‑pretty‑pointless existence.

“Coast is clear,” they announce and Bridge manages a smile. Trying for okay.

“How about it,” Dom prompts again. “You ready to do . . .the thing?”

“Fuck no.” Bridge sighs. The dread is like someone stuck a feeding tube in her throat and poured concrete down it, and now it is sitting thick and heavy behind her rib cage. “Are you sure we can’t just burn it all down?”

“Hmm.” Dom is fiddling with the label maker, jabbing at the buttons. “Well, you’d be the first suspect. And the landlord would be pissed.”

“The landlord could file an insurance claim,” she protests. “Bridge, my love, we are going into that house and we are

doing the thing if it kills us.”

“It might, though,” she pleads. The label gun makes a grinding chirp as it prints something out.

“Here.” Dom peels off the new label and sticks it on Bridge’s shirt upside down, so she can read it.

“Barve?”

“Flying fingers, bonus typos.” Dom shrugs. “Yeah, well, that solves everything.”

“Like magic. Language has power. Feel the courage.” “All right, all right.” Smiling despite herself and the cat’s

cradle of emotion, all the tangled anguish and despair, along with the rage. She is goddamn furious with Jo for leaving her, for being right about the brain cancer, for not calling her sooner. And furious with herself. The guilt that she didn’t come sooner, when Jo told her, three weeks ago. And in general, that she didn’t visit more, call more, pick up on her mom’s erratic behavior: her new squirrelly evasiveness, the trip to Argentina, the dramatic breakup with Stasia, losing her job. But Bridge had been caught up in her own life, her own problems, now minor and stupid in comparison. She’d thought she would have more time. Her mother wasn’t supposed to die.

She slides the key into the scuffed lock, turns it with a click, and pushes the door open, drawing a jangle of protest from the squared‑off antique Chinese bell hanging above it that is supposed to summon blessings or whatever. Dom steps in behind her and taps the doorframe twice, murmuring something in Spanish—a Puerto Rican benediction for the dead.

“That’s really kind,” she says, trying to mean it. She’s not ready for this: Acknowledging the dead. Making a peace offering. Death is pretty fucking real, it turns out. A whole set of realities, all uniquely awful. And now the infuriating bureaucracy that comes after. Sadmin, Dom calls it.

Her dad has already offered to pay for an agency to deal with Jo’s junk, once Bridge has gone through it, and for the memorial service, when she’s ready, and for more therapy. But he can’t be there in person. Unfortunately. Solving everything with money. Solving nothing. She hasn’t told him she dropped out of the business‑degree program he’s paying for and is now working full‑time at Wyvern Books.

Does she even want a memorial? It would have to be in Cincinnati, for her very elderly grandparents, and maybe her uncle would show, and the cousins she hasn’t spoken to in years. But Jo’s students? Her colleagues? There are scores of heartfelt posts on Jo’s Lifebook wall, regrets and blandishments that all run together. Bridge stopped reading them, mechanically clicking Like, Like, Like, so she didn’t have to respond to these strangers who thought they knew Jo but who saw only one version of her. Would anyone come to mourn her life in person? Jo had nuked all her bridges once she got her diagnosis.

Standing in the entry hall, half blocked by the antique

desk with its drawer hanging slack‑jawed, Bridge tries to shift gears, to be barve. She puts on her best poncey British decorating‑show‑host voice and gestures grandly around the shabby interior, at the mismatched picture frames, the bookshelf running the length of the hall. “As you can see, what we have here is a classic take on absent‑minded adjunct‑professor chic.” Always playing the clown. Distract, deflect.

Dom takes in the details, deadpans: “I was expecting more beakers.”

“Beakers is chemistry.” She moves to help them haul in their bags. There’s the reassuring clink of the tequila bottle—because no one should have to do this sober. “Neuroscience is all about electron microscopes and patch clamps and oscillatory . . . majigs. Actual technical terms. And that would all be at her lab at the university.”

“How about disgusting specimens decaying in jars of formaldehyde?”

“Also at the university. We’ll probably need to go clear out Jo’s things there too. There’s a creepy surgery museum you’ll love.”

“Diablo,” Dom says. “You know I’m always down for gruesome medical historia.”

She’s been to the lab here only once, when she visited before Thanksgiving. It was a fusty old building glommed on to the side of the shiny new medical wing, and it looked like every other lab Jo had worked in except this one had her name on the laboratory door and she was so proud to show it off.

The desk drawer isn’t closed all the way, revealing unopened bills (add those to the sadmin pile), and she nudges it shut with her hip, runs her hand over the scuffed green leather desktop with an untrained evaluator’s eye. A hundred bucks? A thousand? Yard sale or online auction?

“Bad breakup or bad case of the poltergeists?” Dom says, tilting their head at the books scattered across the floor.

“Oof,” Bridge says, picking up a copy of The Physics of God haphazardly spatchcocked on the worn‑out runner. She’s still doing the cataloging, the arithmetic. Fifty cents a book? Two dollars? She slides it between Being You: The Neuroscience of Consciousness and Swamplandia!, which seems a fitting title for what she’s going through.

But the mess makes her uneasy. It could have been someone throwing things in anger or her mom having a seizure and grabbing at the shelves. But it doesn’t look scattershot; it looks deliberate, as if someone was searching for something, sweeping books out of the way, rifling through desk drawers. Her heart free‑falls.

“Burglary?” Dom offers.

The state of the bedroom confirms the diagnosis. It’s been tossed; the closets are gaping, all of Jo’s signature black clothing yanked off the hangers. The mattress has been heaved aside; the storage bench of the window seat yawns open. The little desk in the corner is strewn with papers, some spilling onto the floor, a laptop cable dangling use‑ lessly among the stacks.

“¡Coño!” Dom says, whistling. “Fuck,” Bridge agrees.

The living room is in the same state: the sofa knocked on its ass, pillows tossed, art removed from the wall, revealing only ghost impressions instead of hidden safes.

And, yeah, undeniable: In the kitchen, the window by the back door is broken. Glass jags on the earthy red tiles and leaves blown in through the gap. Ransacked cupboards and drawers. The washing machine is open, and the toilet cistern lid has been removed. Like they were looking for hidden cash or drugs?

“Fuck,” she says again, more softly.

“Do you want to call the cops?” Dom says, not meaning it for a millisecond. But she appreciates them saying it out loud, especially considering their whole brown‑queer‑from‑ out‑of‑town thing. The police in Portland have a reputation. “What are they going to do? Not like my mom had any valuables. Or insurance.” Hope is a small and brittle thing — she hadn’t realized she’d genuinely been holding out for secret treasure. “Probably stupid teenagers.” At least it’s not squat‑ ters. She wraps her fingers around her ponytail, tugs it hard. Dom pretends not to notice she’s on the verge of a panic attack, taps the label printer against their cheek. “Look, I can fix this window, easy. Landlord won’t know a thing. But you have a critical job.”

“Keeping it together?”

“That,” Dom agrees. “But also CSI. Go room to room, see if there are any other damages you might be liable for. Make a note of anything important or valuable that’s been stolen so we can decide if you want to call the police or hit up pawnshops after we do the hardware store.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Well, baby, I’m going to take care of the really ugly stuff. You smell that?” Dom wafts their hand in front of their face, sommelier‑style. “That might just be a dead body.” Dom tiptoes over to the refrigerator, which is clearly the source of all evil. “Possibly several. Was your mom killing people and harvesting their brains?”

They fling the door open and Bridge reels back, choking on the odor of rotten food. There’s soft mold fuzzing over a mush of old strawberries, recognizable only by their label, milk that expired a week ago, desiccated leeks, and wilted greens turning liquid in their bags. The power is off, she realizes. Add that to the list.

She hadn’t been able to face coming to the house while Jo was in the hospital. Not alone. Not even to pick up a fresh pair of underwear for her mom. She’d bought them brand‑new from Pioneer Place instead. But now, my God, she wishes she’d come sooner and dealt with this before it became a biohazard. Bridge shoves the door shut, mock gagging. “Can I burn it all down yet?”

Dom shakes their head. Their thumbs do tippy‑taps over the label printer. It grinds out a new message, another typo:

BEWARE!!!!!!!!!

BAGD SMELL LIVES HERE

They slap it on the refrigerator door beneath a shopping list stuck on with a magnet advertising a talk about the science of dreams. And then they print out another:

LEAVE IT TO DOM

“We can trade? I’ll do this if —” Bridge would rather scrub out a thousand refrigerators than sift through the ghosts of her mom’s possessions. Possessed‑sions.

“No chance. I’m not qualified to do your job, so leave me. Leave me here!” Hand to their forehead, sacrifice face. “Go! Before I change my mind!”

“Ugh, fine!” She stomps away to find the circuit breaker and restore electricity to the land. Nosing in to the living room, she rights the sofa turned turtle and replaces the cushions, threadbare and wine‑stained. Probably from the pre‑Thanksgiving potluck Jo held for the students still on campus, her and Stasia’s coterie combined — the neuro kids and lit majors—and Bridge, the dull daughter, half‑assing her way through a business degree when she really wants to do film studies. The guests/students draped themselves over the furniture and spilled into the kitchen and the little garden, the conversation bright and intent, and her mom and Stasia kept touching each other, which was really cute and also embarrassing. Jo seemed so different from her usual spiky self. Playful, happy. Bridge couldn’t remember the last time she’d seen her mom like that.

Stasia hadn’t come to the hospital. It was that kind of breakup, although Bridge is uncertain of the details. Stasia was already at her new job in Baltimore, a million miles away, but she’d sent Bridge an e‑mail with her condolences, something about Jo’s defiance, her fire, how much they’d loved each other. Past tense. The problem with fires, Bridge thinks, is you can’t really contain them. They burn you up, burn you out.

This is a lost cause. How is Bridge supposed to tell the difference between a something‑that‑has‑been‑stolen vacancy and Stasia’s‑shit‑that‑she‑took‑when‑she‑moved‑out one? She needs a before‑and‑after, a spot‑the‑difference. Playing detective. She could e‑mail Stasia, she supposes, the same way she is going to have to track down and mail a few of Jo’s grad students to help her go through her mom’s papers.

The shelves are full of photos turned facedown, which she leaves right where they are. If Jo couldn’t bear to look at them, Bridge isn’t ready yet either. Assorted tchotchkes, including a vivid emerald vase; a rough wooden carving of a man with one glass eye holding a snake ribbed with nails like a giant studded penis (gross); a small brown rubber fetus (more gross). And, up on the top shelf, her mom’s musical instruments: an African thumb piano with double‑stacked metal tines inside a gourd and a sitar with a long neck, tall as the wooden statues. “Giraffe guitar” she used to call it when she was a kid, and her mom used to play it for her, sit‑ ting on the floor next to her bed. She tried to teach her how to play, but Bridge could only manage the thumb piano. A marimba? No, mbira, she remembers. She reaches up on tip-toe to get the sitar down. As she lifts it, a silver key drops out from where it was tucked under the bridge; attached is a plastic tag that reads stasher4u k‑551. She palms it together with the fetus and goes to show Dom.

They are deep in the refrigerator, wearing yellow gloves and a face mask they’ve found somewhere like it’s the peak of Lord Corona all over again, an industrial‑strength black garbage bag emitting a sickly breath at their feet.

“Found your corpse,” Bridge says, holding out the rubber doll, nestled in her palm.

“Ugh!” Dom’s brow furrows in disgust. “What the hell is that?”

“Stasia got Mom into volunteering as an escort at abortion clinics. The pro‑lifers try to hand these to people going in. ‘Look, this is your baby! This is what you’re killing.’ It was an intervention. The more dolls they collected, the fewer the assholes had to terrorize people with.”

“Hmm. Or . . . consider that your mom and Stasia might have been in the pay of Big Rubber Fetus. Maximizing profits by ensuring the lunatics had to go buy even more squeezy embryos.”

“And something else.” She opens her other hand. “What’s that?”

“Key for a storage locker, I think? Maybe that’s where the buried treasure is.”

“Or corpses. We can go check it out tomorrow. Once I’m done with this horror show.” They grab a pile of Tupperware from the freezer and start lugging it over to the sink. All Jo’s prepped meals turned to soggy defrosted mush.

Bridge makes a face. The rotten smell is still lingering. She notices Dom has set out a bowl of fruit and placed a vanilla candle on the windowsill in front of the broken pane of glass. Another peace offering for the spirits. Bridge wishes she had any kind of faith or tradition right now—ritual as a life raft.

“Don’t think I haven’t noticed you’re avoiding the tough stuff. Go, scoot, back to your job.” They tap the upsidedown label on Bridge’s chest. so barve rn.

The bedroom draws her in with a terrible gravitational suck. It’s dim with the rattan blinds down, allowing only a narrow band of light to slice across the floorboards.

She rolls up the blinds, revealing a milky fog of condensation rising halfway up the glass and, beyond it, a moon‑flower tree drooping its pretty poison bells. It takes her a moment to realize there is someone with a bicycle standing across the street, staring at the house. Red hoodie, dark hair, no helmet. Fucking genius over there, she thinks. Head injuries are a serious business. Kill you just as effectively as brain tumors. He raises his hand, less greeting, more Professor, I have a question. She makes like she hasn’t seen him and dropsthe blinds. A few moments later, the doorbell rings. Tinny and electronic and too loud. Her mom would have bought the first one she saw at the hardware store, left it on the preset tone.

“Ignore it!” she yells to Dom.

“I am elbow‑deep in some very bad things. If you think I got time to worry about the damn doorbell—”

It goes off again. And then a sonorous jangle of the Chi‑ nese bell. Fuck off, she thinks. Tinker, tailor, bill collector, or worse—someone wanting to offer their condolences. The emotional capacity to hold someone else’s hand is not something she has right now. She wills whoever it is gone, gone, gone, and, finally, the shadow undarkens the door.

Back to the bedroom.

Picking up papers, trying to decide how to sort them. Documents have colonized the whole surface of the desk in unruly stacks. Leave it another month, Bridge thinks, and the piles will take over the entire house, fill every room, splicing and multiplying like slime mold, the weight bursting the doors and windows, spreading into the street. Wouldn’t that be something?

Most of the stacks are undisturbed, which tells her the robber wasn’t looking for top secret research. She scans the visible pages, but it’s all the same shit Jo had spent her life on. So obsessed with her own epilepsy, she’d made it her specialty: “Inhibitory synaptic transmission and neuroinflammatory responses in the emergence and termination of seizures.”

If Bridge were to collect all these documents and her mom’s notebooks into a great pile and set them alight, would the world really be any worse for it? There she goes again with the arson fantasies. It’s a kink of her generation, wanting to burn it all down.

Oh, and here’s the laptop, buried under a folder of student papers. Really incompetent burglars. Or an indication of how out‑of‑date this clunker is—an ancient Mac circa 2015.

“Hey, Bridge?” Dom calls. Something’s off in their voice, like maybe they did find a damn corpse after all.

“Is it sentient mold?” She heads back to the kitchen. Dom has taken off the mask and is wearing their best what-the-hell-is-this-shit face, which, to be fair, they use quite often. In the sink, several recently decontaminated Tupperware containers are piled up. One is laid out on the table, although even from here, Bridge can tell those tomato stains on the side are never coming out. Like blood, she thinks, but of course it’s not. It’s her mom’s ratatouille. Zucchini and eggplant and onion and vegan chorizo and a shit‑ton of tomato and garlic. Her favorite when she was a kid.

There’s something inside it. You can see the shape through

the stained plastic, and it’s somehow off. About the size of an avocado, but saggy, malformed. Familiar. Foreboding.

“What is it?” she says.

“Fucked if I know. It was buried under the leftovers, emerged like ancient anthrax from the melting permafrost.” “Frozen assets,” Bridge says, realizing. How cryptic, how unnecessary, how freaking typical of her mom. A breeze through the broken window tugs at the candle flame, wafting vanilla and unease across the room.

Dom comes to stand beside her, rubber gloves drip‑drip‑dripping dirty dishwater onto the floor. Bridge’s hands reach for the lid even though she doesn’t want to open it, would in fact much rather do all the paper sorting in the world right now, deal with all the accounts in arrears.

She lifts away the lid. No ceremony. Get it over with. Reveals a lumpen yarn‑y cocoon. It’s grayish yellow, bulbous, and striated, like a spindle wrapped in rotting elastic bands.

Dom leans over her shoulder. “Some kind of disgusting German delicacy? Schmorgenborst?”

But Bridge knows. She recognizes it. From a lifetime ago. From a witch woman in New Orleans. From sitting on the bed in her room while Daddy was at work and her mom strummed dreamy chords on that sitar, and they watched the spinning toy, around and around, and Jo kissed the top of her head and said, Don’t forget to come home.

She’d forgotten. Willfully repressed it, burned through the memory, curled black edges around the hole. Didn’t want to deal with the implications. Which she is reeling away from now, thank you. A fantasy. Make-believe.

“What is it?” Dom says again.

“The dreamworm,” Bridge says and eases her fingers underneath the finely bound mesh of the carapace. It’s brittle and somehow warm, and a strand comes right off in her hand, as easy as if it belonged there—and maybe it does. Gold in the light, not moldy yellow. This is also familiar.

“Am I supposed to know what that is?” Dom asks.

“It opens doors to other worlds.” And before she can think about it, before Dom can stop her, Bridge puts the strand in her mouth—baby bird—and swallows it whole.

Discover the Book

There are infinite realities. She's looking for one . . .

Twenty-four-year-old Bridge is paralyzed by choices: all the other lives she could have lived, the decisions she could have made. And now, who she should be in the wake of her mother’s unexpected death.

Jo was a maverick neuroscientist fixated on an artifact she called the “dreamworm” that she believed could open the doors to other worlds. It was part of Jo’s grand delusion, her sickness, and it cost her everything, including her relationship with her daughter.

But in packing up Jo’s house, Bridge discovers Jo’s obsession hidden amongst her things. And the dreamworm works, exactly the way it’s supposed to, the way Bridge remembers from when she was a little girl. Suddenly Bridge can step into other realities, otherselves. In one of them, could she find out what really happened to her mother? What Bridge doesn’t know is that there are others hunting for the dreamworm—who will kill to get their hands on it.

Bridge is a highly original, reality-bending thrill-ride that could only have come from the brilliant mind of award-winning novelist, Lauren Beukes, about mothers and daughters, hunters and seekers, and who we each choose to be.

.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next