The Art of Horror: 5 Paintings to Creep You Out

Shrouded faces. Dark streets. Impossible creatures. A child’s unblinking gaze. Horror imagery that makes our skin crawl can be found throughout 20th-century painting—especially in movements that took reality and twisted it out of joint. I’m thinking of surrealism, impressionism, and the stark, off-kilter realism of artists like Edward Hopper. The mood is even more disquieting in paintings that didn’t set out to evoke the heart-pounding fear of what we think of as “horror.” These scenes vibrate with dreamlike loneliness and empty spaces begging to be filled by the unknown.

Shrouded faces. Dark streets. Impossible creatures. A child’s unblinking gaze. Horror imagery that makes our skin crawl can be found throughout 20th-century painting—especially in movements that took reality and twisted it out of joint. I’m thinking of surrealism, impressionism, and the stark, off-kilter realism of artists like Edward Hopper. The mood is even more disquieting in paintings that didn’t set out to evoke the heart-pounding fear of what we think of as “horror.” These scenes vibrate with dreamlike loneliness and empty spaces begging to be filled by the unknown.

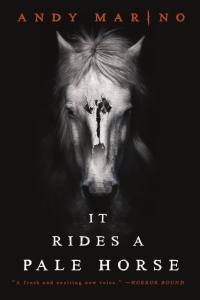

As a wannabe-painter-turned-writer, taking inspiration from such visions was inevitable. Here are five paintings that appear in my new novel, It Rides a Pale Horse—a story of small-town secrets, occult history, and one very powerful art forger.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper

I don’t know what alchemy Hopper tapped into to turn ostensibly charming elements into a study of desolation. There’s the server in his immaculate whites, the snappily dressed mid-century men, the woman in the bright red dress. The coffee shop is a clean, well-lighted place. What really gets under my skin is the street: sterile and empty, like a movie backlot or a museum exhibit. It’s all steeped in the overriding sense that nothing is going on and nothing will ever change—and none of us are looking at each other.

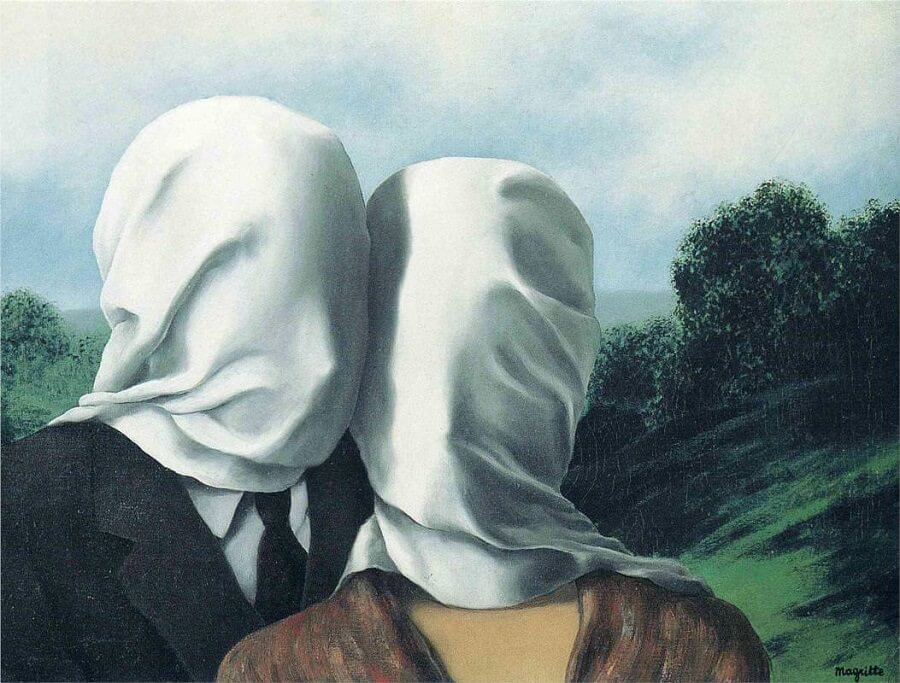

The Lovers

René Magritte

What a nice day for a young couple to take a walk in the countryside and stare directly at you from behind their clean white shrouds. There’s a softness to the fabric that’s almost comforting, like you can smell the freshness of the laundry. This isn’t some greasy, horror-movie, bag-over-the-head moment. Somehow, this is far creepier. A man and a woman decided to wear their finest shrouds outside on a clear day for reasons you’ll never understand. And when you came upon them in the field, they turned as one to face you…

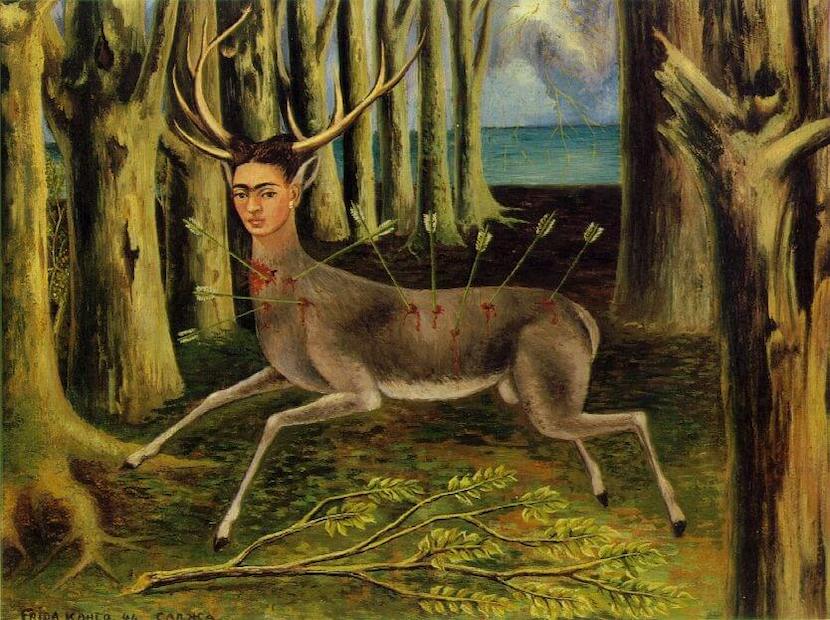

The Wounded Deer

Frida Kahlo

This painting exudes both the dark mysticism of folk horror and the queasiness of body horror. Every element is designed to be as unsettling as possible: The placid look on the artist’s face, as if she’s totally unconcerned that she is 1) a deer and 2) riddled with arrows. The visceral action of the wounds—the arrow to the neck is spraying blood like it’s landing at the same time you’re seeing the painting. And then there’s the sickly yellow-green cast to the forest setting, not to mention the oddly flat depth of field to the whole scene.

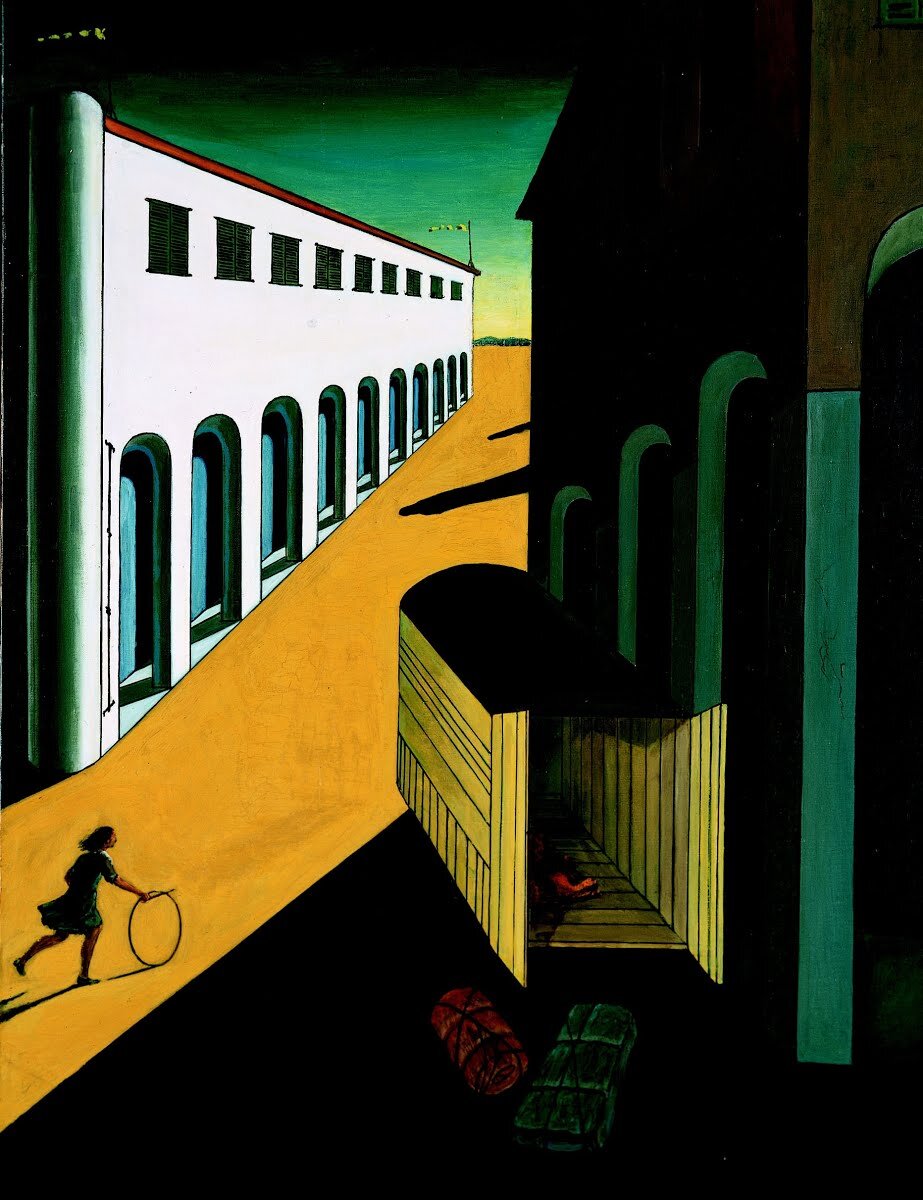

Mystery and Melancholy of a Street

Giorgio de Chirico

Like those exquisite moments of steadily mounting dread in the best horror stories, de Chirico squeezes every drop of fright out of what’s about to happen. Your eye is drawn to the central image: the shadow of a figure lurking just out of sight. Here’s where the artist ups the ante: He takes that standard fear of the unknown, of the dark figure just around the corner, and sets it in a landscape that defies reason. The perspective is all wrong. The buildings diminish toward clashing vanishing points. The vehicle is parked at an impossible angle. The girl with the hoop racing toward the hidden figure will either run uphill or downhill before she finds out what awaits her.

Young Mother Sewing

Mary Cassatt

At first glance, this is a peaceful scene. The details are both sharply observed and softly rendered: the exact positioning of the mother’s hands as she sews, the slight bend in her neck, the design on the Delft vase. But like the most effective horror, this painting is incredible for what it suggests. The longer you look the more you see—and feel. The little girl is staring out through the canvas at you, while the mother is oblivious to your presence. Who are you? Why can the little girl see you but the mother seemingly can’t—or won’t? The last word on the scene comes from a hint of darkness in the empty yard outside, gathering in the margins of swirling brushstrokes.

Discover the Book

Andy Marino is the author of the horror novels It Rides a Pale Horse and The Seven Visitations of Sydney Burgess. He also writes historical fiction for young readers, most recently Escape From East Berlin.

The Larkin siblings are known around the small town of Wofford Falls. Both are artists, but Peter Larkin, Lark to his friends, is the hometown hero. The one who went to the big city and got famous, then came back and settled down. He’s the kind of guy who becomes fast friends with almost anyone. His sister Betsy on the other hand is more… eccentric. She keeps to herself.

When Lark goes to deliver one of his latest pieces to a fabulously rich buyer, it seems like a regular transaction. Even being met at the gate of the sprawling, secluded estate by an intimidating security guard seems normal. Until the guard plays him a live feed: Betsy being abducted in real time.

Lark is informed that she’s safe for now, but her well‑being is entirely in his hands. He's given a book. Do what the book says, and Betsy will go free.

It seems simple enough. But as Lark begins to read he realizes: the book might be demonic. Its writer may be unhinged. His sister's captors are almost certainly not what they seem. And his town and those within it are… changing.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

WHAT TO READ NEXT