On Horror and the Creations that Shape Us With Tananarive Due

NS: You’re an established author, lecturer, and producer. Where did you get your start? Was horror something you were always interested in? Do you remember your first encounter with the horror genre?

NS: You’re an established author, lecturer, and producer. Where did you get your start? Was horror something you were always interested in? Do you remember your first encounter with the horror genre?

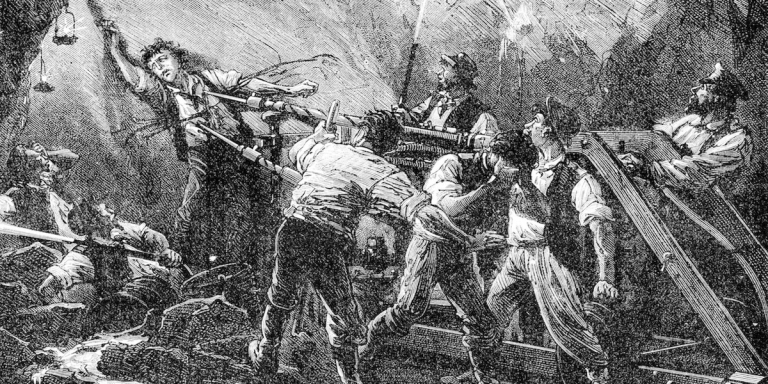

TD: I got my love of horror from my late mother, Patricia Stephens Due, who was a civil rights activist who wore dark glasses most of the time after the age of 20 because a police officer in Tallahassee, Florida, threw a teargas canister in her face during a nonviolent protest. She raised us on classic horror movies on Saturday Creature Features and gave me my first Stephen King book at the age 16—and by then I was HOOKED. Unlike my mother, who I think used horror to blunt racial trauma, as a child I saw horror as more of a rollercoaster ride. But now that I’m older, I have a better understanding of how horror can help us process trauma and overcome our internal “monsters.”

NS: You teach Black Horror and Afrofuturism *which sounds amazing* at UCLA. For those who don’t know, can you give us a brief summary of these two topics and how they capture the zeitgeist of historical and modern horror narratives?

TD: To me, Black Horror is loosely defined as horror by Black creators (or allies) telling a story from a Black character’s POV where the character has agency and impact, not one of the many tropes that have plagued Black characters in horror: primarily the Sacrificial Negro, the Magical Negro, the First to Die, the Spiritual Guide, etc. (You can still see these tropes alive and well around marginalized characters today.) Black Horror can be everything from GET OUT, where racism is the monster, to a movie like J.D. Dillard’s SWEETHEART, which has little (if anything) to do with race or racism, but give a Black character primacy in the story.

Afrofuturism, the way I teach it, is also very broad: it’s the speculative fiction of the African Diaspora, though Africanfuturism, for example, is also its own separate subgenre. It’s Black science fiction, fantasy, magical realism and horror.

NS: The Between, which will be reissued on 10/5, follows Hilton, a man slowly losing grip of reality as he battles ‘the psychotic stalking of his family and the unseen enemy that haunts his sleep’. It’s your first novel and was nominated for the 1996 Bram Stoker Award. What drew you to tell Hilton’s story? How has your approach to writing changed since The Between was published in 1995?

TD: After Hurricane Andrew in 1992, my hometown of Miami was so devastated that it helped me come up with the premise: what if you woke up in a different world than the one you’d gone to sleep in? Many things have changed, but some things are the same? And what if a white supremacist terrorist was stalking you through all of these timelines, personifying death?

I’d been writing many short stories at the time, mostly with white protagonists, and THE BETWEEN was my ah-ha moment: “What if I put MY experiences in a novel?”

I’d grown up in newly integrated neighborhoods near Miami, subjected to verbal attacks and vandalism by neighbors, so THE BETWEEN was my first novel where I included my own true-life experiences. I have to admit that if I wrote it today, I might write a different ending—and perhaps I might have started the story in a less unsympathetic moment for Hilton as an adult—but I intentionally did not change the novel because I wanted it to reflect who I was when I wrote it.

NS: I want to discuss Black Horror a little more because it’s a topic that has really been thrust into the spotlight in recent years, particularly thanks to directors like Jordan Peele. As an activist yourself, how do you see the narrative on Black stories and Black expression in the creative spaces shifting and where is still room for growth?

I think Black Horror is an extremely powerful tool to help validate and visualize trauma, especially in metaphorical form, as in Jordan Peele’s The Sunken Place. I don’t think it’s an accident that my mother was drawn to horror, even when there were no Black characters or discussions of race, because there’s something about trauma that horror can soothe very specifically because it relies so much on dread and survival behaviors. But I do think both Black audiences and creators have some growing to do: audiences need to realize that if THEY specifically don’t care for horror, that doesn’t mean they should advocate doing away with Black horror altogether. (It’s a thing.) And as creators, especially in visual media, we need to recognize that Black Americans are already in a state of trauma, so visualizing lynchings and racialized violence is a very limited way to express horror trauma—it’s less retraumatizing to use metaphors and fantasy violence that won’t remind audience members of incidents they have actually suffered in their family histories. But it’s a learning process for all of us.

NS: What are some of your favorite horror movies and/or books—new or old?

TD: Of course I’m a huge fan of GET OUT and Nia DaCosta’s new CANDYMAN. Some favorites off the top of my head: HIS HOUSE, IT FOLLOWS, THE BABADOOK, HEREDITARY, THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS, NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET, THE EXORCIST and NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. As for horror books…almost anything by Stephen King, THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS by Stephen Graham Jones, and anything by Victor LaValle.

NS: Are there any projects you’re currently working on that you can share?

TD: I finished a long-term project over the pandemic called The Reformatory, based on the true-life history of my great-uncle’s incarceration at the Dozier School for Boys in Marianna, Florida, in the 1930s. Rather than writing a nonfiction book about it once I learned about Robert Stephens, I decided to fictionalize his story, set it in 1950, and add ghosts to help express this facility’s history of violence rather than subjecting my readers to several assaults of all types against young boys. A “haint” and a living boy must join forces to bring down a psychopathic warden and make sure the story of The Reformatory is told.

Order the Book

When Hilton was a boy, his grandmother sacrificed her life to save him from drowning. Thirty years later, he begins to suspect that he was never meant to survive that accident, and that dark forces are working to rectify that mistake.

When Hilton's wife, the only elected African American judge in Dade County, Florida, begins to receive racist hate mail from a man she once prosecuted, Hilton becomes obsessed with protecting his family. The demons lurking outside are matched by his internal terrors—macabre nightmares, more intense and disturbing than any he has ever experienced. Are these bizarre dreams the dark imaginings of a man losing his hold on sanity—or are they harbingers of terrible events to come?

As Hilton battles both the sociopath threatening to destroy his family and the even more terrifying enemy stalking his sleep, the line between reality and fantasy dissolves . . .

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next