The Last Days of John Lennon

Chapter One

He sits in the airplane, inside a cloud of cigarette smoke. He opens his wallet and looks at the permit for his handgun. He was going to buy a .22 when the salesman steered him toward a .38.

Well, if you get a .22 and a burglar comes in, he’s just going to laugh at you, the salesman said. But if you have a .38 nobody’s going to laugh at you. Just one shot with a .38 and you’re going to bring him down.

The safest way to transport the weapon, the Federal Aviation Administration told him over the phone, was to pack it, along with the ammo, inside a suitcase—which he did. The gun was purchased legally—personal protection, he told the salesman—in Hawaii.

The ammo is another matter. Hollow-points are illegal in New York. If security decides to search his bag, he could be arrested.

It’ll be fine, he keeps telling himself as he exits the plane. The biggest threat these days is skyjacking. He doesn’t look like a terrorist.

He stands at the carousel inside LaGuardia, keeping an eye out for his bag while covertly watching the security people from behind the reddish-brown tinted lenses of his aviator-style eyeglasses.

No one comes looking for him.

The people he passes—business travelers and those who have come to the Big Apple to enjoy a few days of Christmas shopping—don’t even acknowledge his presence. No eye contact, not a nod hello, nothing.

It’s like I’m invisible.

And in a way, he is. He’s been invisible his whole life. He’s not remarkable in any way, which gives him a distinct tactical advantage. He can blend in anywhere, and he doesn’t look threatening.

And I have to stay that way. I have to appear normal at all times.

Which means staying out of his head as much as possible.

His mind is a dangerous neighborhood.

He steps outside the airport, into the bright sunshine. The air is unseasonably warm. He drops his suitcase at the curb and, sweating and out of breath, hails a cab, his thoughts turning to the five bullets packed next to his gun. The FAA also told him that changes in air pressure could damage them.

He only needs one of them to work.

The five hollow-point Smith & Wesson +P cartridges are designed for maximum stopping power—and maximum damage. When one hits soft tissue, the tip mushrooms into a lethal miniature buzz saw that spins and bounces its way through the body, shredding tissue and organs.

One shot is more than enough to ensure John Lennon’s death.

A yellow cab slides up next to him. He puts his suitcase in the trunk, then gets into the back seat. He gives the driver the address for the West Side YMCA, off Central Park West. It’s only nine blocks away from his true destination.

He puts on his best smile and tells the cabbie, “I’m a recording engineer.”

The taxi pulls away from the curb.

“I’m working with John Lennon and Paul McCartney.”

The cabbie ignores him.

He glares at the back of the man’s head. If you only knew what I’m about to do, you would be paying attention to me. You wouldn’t be treating me like some nowhere man.

“Nowhere Man” is a song by his favorite group of all time, the Beatles. Well, they used to be his favorite, until they broke up. And he still hasn’t forgiven John Lennon for saying that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus.

That was blasphemy.

The taxi gets in line with the bumper-to-bumper traffic heading into Manhattan. Everyone is rushing to Rockefeller Center. A sixty-five-foot Norway spruce has just been delivered, and electricians are working feverishly to prepare for the annual Christmas tree-lighting ceremony, which is only a few days away.

He takes out a bag of coke. Snorts a line off his fist.

The cabbie is now watching him in the rearview mirror.

“Want some?”

The driver shakes his head and returns his attention to the road.

The coke isn’t working its magic. Instead of feeling a wave of intense pleasure, he’s sweating and working himself into a rage, all of it aimed at Lennon.

“But I’d plug him anyway,” he mutters. “Six shots through his fat, hairy belly.”

He arrives at his destination. He pays his fare, and as he steps out of the cab, he imagines police swarming him, their weapons drawn, ready to arrest him. He sees himself locked inside a jail cell for the rest of his life.

The thought brings him comfort.

Peace.

He turns back to the driver. “I’m Mark Chapman. Remember my name if you hear it again.”

Chapter Two

Isn’t he a bit like you and me?

—”Nowhere Man”

You’ll like John,” Paul McCartney’s friend Ivan Vaughan says. “He’s a great fellow.”

Paul knows John Lennon, but only by sight, really. John is older—almost seventeen—and the two have never spoken, even though they ride the same Allerton-to-Woolton bus to school.

Today John’s singing with his band, the Quarry Men, at the St. Pete’s Church fete, and fifteen-year-old Paul and Ivy have bicycled over to check them out. Well, Ivy’s interested—Paul wants to check out the girls.

It’s Saturday, July 6, 1957, and already hot when the Quarry Men take the outside stage.

John’s wearing a “shortie”—a knee-length coat—over a checkered red-and-white shirt and black drainpipe jeans. He starts to cover the Del-Vikings’ doo-wop tune “Come Go with Me.” Paul has heard the American song only a handful of times, on the Decca Records show on Radio Luxembourg and playing in one of the record-shop booths.

Paul half listens and goes back to scouting the crowd. He’s thinking about which girl to approach first when he hears John change the lyrics without skipping a beat. Paul knows a lot about the guitar, and he can’t figure out what style John is playing as he breaks into a rockabilly cover of Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula.” John dominates the stage. Owns it.

Which isn’t much of a surprise. Everyone knows John Lennon is cocky and confident—and a local Ted, or Teddy Boy. Here in Liverpool, the Teds, with their long sideburns and oiled-up hair swept together in the back like a duck’s arse, are hard, rebellious working-class men and boys who love getting into fights.

Paul follows Ivy inside the St. Peter’s church hall, where the band’s setting up to play another set. John is widely considered a hoodlum. He lives with his aunt instead of his mum. The talk around town is that John’s father abandoned him, and now John’s mum lives in sin with another man. They had two daughters out of wedlock.

The memory of Paul’s own mother suddenly crowds his thoughts.

This past October, on the twenty-ninth, Mary McCartney went into the hospital. She didn’t tell him or his brother, Mike, why. Then, two days later, on Halloween, she died—from breast cancer, Paul found out eventually. Eight months have passed, and the loss still pierces him.

And that’s when he became consumed by music. As his brother puts it, “You lose a mother—and you find a guitar?”

If you can sing or play an instrument, Paul, you’ll always be invited to the party, his dad, Jim, a jazz musician in his youth, tells him. Paul starts on the trumpet, but after hearing Elvis Presley and Lonnie Donegan, the so-called King of Skiffle, he takes the horn back to the Rushworth and Dreaper music shop and swaps it for a Zenith guitar.

The problem is he’s left-handed, and guitars are made for right-handers. So he’s learned to play the guitar in reverse—right hand working the fret board, shaping the chords, while strumming with his left.

Paul picks up one of the guitars in the hall and starts to play “Twenty Flight Rock”—a song Eddie Cochran performed in the movie The Girl Can’t Help It—which he only learned a few days ago. It’s an immensely tricky song to play, even more so if you’re forced to play wrong-handed. But Paul’s only ambition in life is to be like Elvis, so he puts a lot of swagger into his impromptu performance. John stands nearby, his eyes narrowed, almost slanted. It’s the same look he had earlier while performing onstage, as though he were looking down on the crowd.

And now he’s looking down on me. Thinks I’m just a fat schoolboy.

* * *

Paul finishes the song, then starts to tell John about how he works out his own lyrics: “Like I’m writing an essay or doing a crossword puzzle.”

John nods, uninterested.

Paul goes over to a nearby piano. He sits and starts to play Jerry Lee Lewis’s hit song “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.” Paul really gets into the music, even pounding the keys like Jerry Lee does.

Paul feels John’s arm on his shoulder. John leans over, contributing a deft right hand in the song’s upper octaves. He’s drunk, Paul realizes.

When they finish playing, John announces that it’s time for the pub. Paul’s heart thunders with excitement. The coolest kid in Liverpool has just invited me.

Bubbling beneath it is another feeling: apprehension. Every adult, including Paul’s dad, says about John, He’ll get you into trouble, son. John Lennon, with his intimidating glare and his sideburns and upturned collar. You saw him rather than met him.

Now that Paul has, he’s sticking around.

Chapter Three

Won’t you join together with the band?

—”Join Together”

John doesn’t care that Paul is only fifteen. Musically, he’s as serious as John is about rock ‘n’ roll. Paul’s already composing songs and knows how to play the piano.

And he plays the guitar perfectly—upside down.

Should I ask Paul to join the band? What if he tries to take over? John ponders these questions as he stands on the cobblestones outside the Cavern Club, in central Liverpool, where the Quarry Men played their first gig. The club, located under a fruit and vegetable warehouse, is a well-known jazz venue. “We never get auditions because of the jazz bands,” John says, but now jazz is on the way out, replaced by skiffle, a British version of jug-band music that the Quarry Men play.

But John’s true love is American rock ‘n’ roll, and tonight he wants nothing more than to get onstage and bend the crowd’s ears back with its raw rhythms. Except the Cavern Club doesn’t allow that type of music. No place does.

Rock ‘n’ roll has had a bad reputation ever since the American film Rock Around the Clock came to Britain last year and waves of teenagers ripped up their cinema seats so they could dance to the title track, by Bill Haley and His Comets. Now the old guard is terrified of the music’s destructive power. The BBC won’t play it on radio or TV.

But rock ‘n’ roll isn’t going away. Until just recently, the number-one song in the country was Elvis Presley’s “All Shook Up.” John first heard about Elvis from a schoolmate quoting a music magazine. New Musical Express featured this strangely named American singer who had women screaming and fainting when he sang “Heartbreak Hotel” and thrust his hips onstage.

John bought the record and rushed home with it. He lives with his aunt, Mimi Smith, not his mum, Mimi’s sister Julia. At night, John gets underneath the bedcovers with his portable radio and turns the volume down low to listen to medium-wave Radio Luxembourg, which plays all the American rock ‘n’ roll hits.

Mimi does not approve of rock ‘n’ roll. She thinks people who listen to it are “low class” and wants him to stay focused on his schoolwork. Mimi doesn’t know that he’s formed a band, let alone that he has a gig tonight.

“A guitar’s all right, John, but you’ll never earn a living by it.”

But John’s sure she’s wrong. “I wanted to write Alice in Wonderland and be Elvis Presley,” he says, and as far as he’s concerned, he can—and will—do both. A few days ago, he’d discovered that Mimi had yet again “cleaned” his room, tossing out all his drawings and poems. He was furious and didn’t hold back: You’ve thrown my fuckin’ poetry out, and you’ll regret it when I’m famous.

John wonders what Mimi’s reaction would be if she found out that the source of his forbidden Ted clothes is Julia, who loves Elvis just as much as he does. Julia, unlike puritan Mimi, has a record player and loves to sing and dance and toss about her gingery hair. She even bought him his first guitar, an acoustic Spanish flamenco-style model with steel strings that have cut painful grooves into his fingertips from his constant practicing.

By the time John meets up with his mates at the Cavern Club that evening, he’s come to a decision about Paul McCartney. “It went through my head that I’d have to keep him in line,” John later reveals. “But he was worth having.” John seeks out a mutual friend, Pete Shotton, to extend the invitation.

* * *

A four-string guitar strapped around his shoulder, John stares out at the middle-aged audience. God, they look stiff. He turns to the band and cues them.

Rod Davis, the banjo player, sidles up next to him, frantic. “You can’t do that,” he says. “They’ll eat you alive if you start playing rock ‘n’ roll in the Cavern!”

John ignores him and turns back to the crowd.

Let’s give ’em a taste of the King.

John belts out Elvis Presley’s “Don’t Be Cruel.” The Quarry Men follow.

The manager hears the chorus—Don’t be cruel to a heart that’s true—and rushes to the stage with a note.

Cut out the bloody rock ‘n’ roll.

John tosses the note aside and channels Jerry Lee Lewis and his new favorite, Buddy Holly and the Crickets, as he tears into another rock ‘n’ roll number from the American pop charts.

* * *

John invites Paul to play a gig with the Quarry Men at New Clubmoor Hall in Norris Green, the northern part of Liverpool—a good distance by bus from where they all live.

They open with “Guitar Boogie” by Arthur Smith and His Cracker-Jacks. The guitar solo is easy to play, a simple twelve-bar. But not only is this Paul’s first time playing with the band, it’s also his first guitar solo ever.

Onstage, John and Paul take turns singing. When one leads, the other harmonizes. John’s strength is holding the lower key; Paul’s voice is more suited for the higher range.

Paul starts his guitar solo.

His fingers won’t move. It’s like they’re stuck to the fret board.

Paul fights his way through it until his round face is flushed. Wet.

After the show, everyone is looking at him, and he’s frightened. Yet he’s resolute on one point. “It wiped me out as a lead guitar player, that night,” Paul says. “I never played lead again onstage.”

* * *

John is in his bedroom, composing a poem on his portable typewriter, when he hears a knock on the back door, off the kitchen.

Mimi calls up the stairs: “John, your little friend’s here.”

She uses this patronizing tone with all his friends. “I thought John and Mimi had a very special relationship,” Paul later says. “She would always be making fun of him and he never took it badly; he was always very fond of her, and she of him.” Even though she “would take the mickey,” Paul says, “I never minded it, in fact I think she quite liked me—out of a put-down I could glean the knowledge that she liked me.”

Mimi thinks Paul is the one “taking the mickey out” of her with his posh accent. “I thought, ‘He’s a snake charmer all right,’ John’s little friend, Mr. Charming. I wasn’t falling for it.”

John enters the kitchen and finds Paul McCartney standing there, Mimi eyeing the guitar in Paul’s hand and reminding them both to keep the noise down and not bother her student lodgers.

The University of Liverpool students Mimi takes in to supplement her widow’s state pension don’t interest John, though he’s also earned a place at the Liverpool College of Art after a portfolio review of his cartoons and caricatures. Maybe I can get a job drawing gorgeous girls for toothpaste posters is his thought.

“We’ve got this song, Mimi, do you want to hear it?” John asks his aunt.

“Certainly not,” Mimi scoffs. “Front porch, John Lennon, front porch.”

John closes the door, telling Paul that he likes it out on the porch “as the echo of the guitars bounce[s] nicely off the glass and the tiles.”

The moment Mimi leaves the house, they race upstairs and play Little Richard records. They both worship the singer from Macon, Georgia, and Paul can even mimic those trademark hollers and screams on “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally.”

But Elvis Presley is God, and they are his acolytes. They don’t just play Elvis records—they also analyze them, trying to figure out the chord progressions, every single sound. All the rock songs they know are played with C, F, and G or G7. They’re determined to crack the chords to Elvis’s “Blue Moon,” but it’s not until early winter that they discover that C, A minor, F, and G are the exact same chords Paul Anka used in his hit “Diana,” recorded in 1957, when he was fifteen, the same age as Paul.

John’s excitement is so fierce, so intense, that it’s nearly blinding. It confirms what he’s known all along: music is the reason he was put on this earth.

And he’s going to do music with Paul McCartney.

Help me get my feet back on the ground.

—”Help!”

Paul walks home, still riding the high of finally cracking the chord progression for “Blue Moon.” He prefers riding his bicycle, but he can’t do that when he brings his guitar, since it doesn’t have a case.

His father still has no idea he’s hanging out with John Lennon, but it doesn’t matter, really, whether his dad likes John. They’re friends now. Musical brothers in arms.

John, of course, knows how Jim McCartney feels about him. John gives Paul some cleverly worded advice: Face up to your dad! Tell him to fuck off!

He’s thinking about it.

Paul wishes he could find a way, some combination of words, to explain to his father just how deep John is. Not only in his passion for music but also in his art. That John composes poetry; that he could be a great writer.

Paul takes a shortcut via the Allerton Municipal Golf Course, which is closed for the season.

Paul is good at the guitar. And he’s pretty good at singing. But playing and singing…that takes practice. And what a better place than the middle of an empty golf course?

Paul stops walking to listen. A couple of times, people have caught him, and when they do, he immediately stops playing and starts walking.

But right now, in the pitch black, he’s pretty sure he’s alone. He straps the guitar over his shoulder and, in his mind’s eye, sees himself stepping onstage, in front of thousands of people. The crowd goes wild, clapping and screaming his name.

Paul steels himself. Summons his nerves.

He starts to play.

Sings.

The crowd roars in approval. The women are hysterical. Some have fainted.

Paul is getting into a good rhythm, singing at the top of his voice, when he hears someone behind him shout: “Hey!”

Paul stops playing.

Whips around and sees a man—a policeman—approaching him.

Oh, God, I’m going to get arrested for a breach of the peace.

“Was that you I heard playing the guitar?”

Paul considers lying, even though it’s crystal clear he’s been caught red-handed.

Even as his heart pounds, he decides to go with the truth.

“Yes, sir.”

The policeman, tall and burly, towers over him. If he gets arrested, what will he tell his dad?

“Can you give me guitar lessons?” the man asks.

Chapter Four

I was so much older then

I’m younger than that now.

—”My Back Pages”

John and Paul’s new project is to crack the intro to Buddy Holly’s “That’ll Be the Day.”

They’ve been going at it for weeks.

The friends sit in chairs, practically toe to toe, and watch each other play guitar. It’s like “holding a mirror up” between the left-handed Paul and the right-handed John.

John rarely goes to class. When he does, he’s outspoken. Rebellious. Argumentative and stubborn.

“I was aggressive because I wanted to be popular,” John later says. “I wanted to be the leader…I wanted everybody to do what I told them to do, to laugh at my jokes and let me be the boss.”

At Liverpool College of Art, some classmates and teachers like him, though many despise him.

But no one ignores him.

Still, he is most in his element at the “eyeball to eyeball” sessions he and Paul undertake at Paul’s empty home. Every weekday except Mondays, Paul cuts school at the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys, and they take the green double-decker 86 bus—sitting up top, outside, so they can smoke.

John finds the well-worn furniture, with its protruding springs hidden by cotton covers, comforting and warm—much more like his mum’s than Mimi’s more austere house. John takes a seat and removes his glasses from his pocket.

Paul is staring at him.

You never knew I wore glasses because I never wear them. When he started having vision problems, Mimi took John to the eye doctor. The other kindergartners ridiculed the thick lenses needed to correct his severe nearsightedness, though, and he still refuses to wear his glasses in public.

But he feels comfortable with Paul, who’s like a younger brother. One who’s insanely talented, ambitious, and determined.

They go at the chords over and over.

John works his guitar until he nails the intro.

To celebrate, Paul lights up his dad’s spare pipe with a pinch of tobacco they find in the tea caddy.

John takes a puff and thinks, Practically every Buddy Holly song is three chords. We should write our own.

Though John ignored Paul the first time he talked about his songwriting techniques, now he’s curious and draws him out.

Paul starts at the beginning. “I’d either sit down with a guitar or at the piano,” he says, “and just look for melodies, chord shapes, musical phrases, some words, a thought just to get started with.”

John wants in on this creative process, but it doesn’t take long for him to discover that songwriting is hard.

Their first collaboration, “Too Bad About Sorrows,” remains incomplete, as does their follow-up, “Just Fun.” The next one they work on, “Because I Know You Love Me So,” has a Buddy Holly feel to it. They’ve already worked out the harmony.

Paul turns to a fresh page in his notebook to start a new song. Up at the top, he writes, “Another Lennon-McCartney Original.”

Order Now

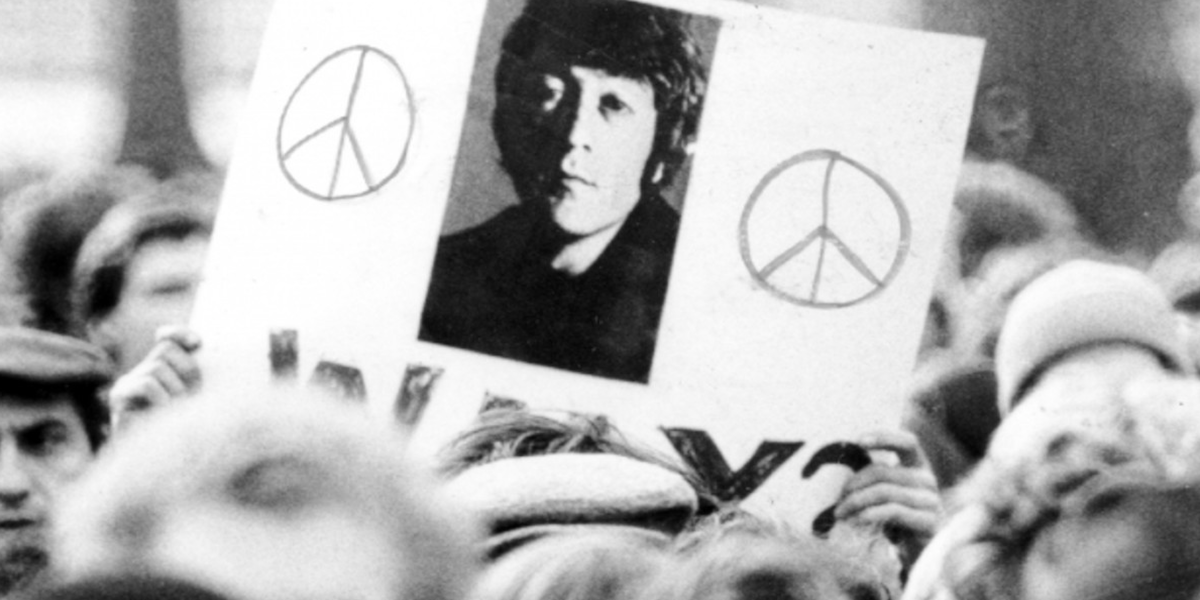

With the Beatles, John Lennon surpasses his youthful dreams, achieving a level of superstardom that defies classification. “We were the best bloody band there was,” he says. “There was nobody to touch us.” Nobody except the original nowhere man, Mark David Chapman. Chapman once worshipped his idols from afar—but now harbors grudges against those, like Lennon, whom he feels betrayed him. He’s convinced Lennon has misled fans with his message of hope and peace. And Chapman’s not staying away any longer.

By the summer of 1980, Lennon is recording new music for the first time in years, energized and ready for it to be “(Just Like) Starting Over.” He can’t wait to show the world what he will do.

Neither can Chapman, who quits his security job and boards a flight to New York, a handgun and bullets stowed in his luggage.

The greatest true-crime story in music history, as only James Patterson can tell it. Enriched by exclusive interviews with Lennon’s friends and associates, including Paul McCartney, The Last Days of John Lennon is the thrilling true story of two men who changed history: One whose indelible songs enliven our world to this day—and the other who ended the beautiful music with five pulls of a trigger.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use