Read the Excerpt: Everybody Knows by Jordan Harper

Chapter One

Chapter One

Mae

THE CHATEAU MARMONT

Los Angeles burns.

Some sicko is torching homeless camps. Tonight they hit a tent city in Los Feliz near the 5. The fire spread to Griffith Park. The smoke makes the sunset unbelievable. The particles in the air slash the light, shift it red. They make the sky a neon wound.

Mae waits outside the secret entrance to the Chateau Marmont. She watches Saturday-night tourists wander Sunset Boulevard, their eyes bloodshot from the smoke. They cough and trade looks. They never thought the Sunset Strip would smell like a campfire.

Mae moves around the sidewalk like a boxer before the fight. Her face is sharp and bookish, framed in a Lulu bob. She wears a vintage floral jumpsuit. She’s got eyes like a wolf on the hunt — she hides them behind chunky oversized glasses. Nobody ever sees her coming.

She shifts her weight from foot to foot — these heels weren’t made for legwork. She put them on for a first date she canceled twenty minutes ago when she got the text from Dan. No big loss — the date was with a stand-up comedian she met on Bumble. Comedians on a date tend to treat a woman like a test audience, or like their shrink, or they think you’re a chucklefucker and they don’t even have to try.

Dan’s text had read hannah chateau asap followed by the number for Hannah Heard’s new assistant. Dan’s text was cryptic per usual. The rules say keep as much as possible UNSAID.

The Chateau Marmont: the hippest no-tell hotel in the world.

This shabby-chic Gothic castle slouching against the base of the Hollywood Hills. The way to the hotel proper is up a small winding road to Mae’s left. This secret entrance on Sunset leads straight to the grotto where the private cottages are. The unmarked door built into the white-brick wall is made of green cloth—someone could slash it easily and go marauding among the rich and famous. But no one ever does.

Chateau jobs tend to be messy. They tend to be drama. They tend to be a fucking blast. Hannah Heard increases the odds of all three exponentially.

The green-cloth door swings open. The girl on the other side is early twenties. She’s got blue hair and an Alaska Thunderfuck T-shirt worn as a dress—her vibe is manic pixie e-girl. Her eyes are wide like a rabbit in a trap. Mae pegs her as having a milk-brief life in the Industry. It’s not that the girl feels fear—it’s that she lets it show.

The rules say wear your mask tight.

“I’m Hannah’s assistant. Shira.” She swallows her voice before it can make it all the way out of her mouth. The sort of on-its-face weakness that makes Mae chew the inside of her cheek. “You’re the publicist?”

“Something like that. Take me to her.”

In the grotto everything is Xanax soft. The hooting of the Strip fades away. Even the smoke stench from the wildfires is blotted somehow. Everything rustles dreamlike, all bougainvillea and bamboo and art deco stained glass. On each side of the grotto sit six little cottages. There is a brick lagoon at the center of it, still and tranquil, full of water lilies and mossy stones.

One thing breaks the dream: The concrete Buddha at the foot of the lagoon is spilled on his side. The fall decapitated him. His severed head smiles up at the sky. Mae figures it must have just happened. The Chateau is pretty good about hiding bodies.

Shira sees Mae looking at the toppled god. She says, “She had a long flight.”

The girl knows how to say things without saying them. Maybe she’ll make it here after all.

Hannah’s cottage smells like an industrial dump site—the ammonia bite of whatever they’ve been smoking makes Mae’s eyes tear up. She turns to the assistant before she can close the door behind them.

“Leave it open.”

“The smell—”

“Nobody cares.”

The cottage’s front room is beyond trashed. Clothes in piles tumbling out of Gucci luggage, this mix of couture and sweatpants. Room service trays and empty bottles crowd every surface. A plate of fries jellied in ketchup. Kombucha bottles turned into ashtrays. A tray of Dom Pérignon and Cool Ranch Doritos. On the table a baggie of something yellow-white like chunks of bone sits next to a well-used glass pipe. Mae looks down — she’s kicking rock-hard dog turds. It must have taken weeks to do this damage—but the assistant said Hannah just flew in. Hannah’s running a tab when she’s not even in town—and the cottages go for a grand a night.

Two men and a woman slouch on the vintage couch like throw pillows. Lifestyle and face fillers have turned them into triplets. Mae knows the type: remoras, fish that eat the trash off the body of a shark. They take in Mae with blank fishy eyes.

Mochi, a yappy little dog, white and fluffy when groomed but now grayish and dreaded, yaps in from the kitchen, a shrill little herald announcing the entrance of the one and only Hannah Heard.

You know her face. Even with her hoodie pulled up and the oversized sunglasses, you know it. The knowing floats in the air like wildfire smoke. Even if you didn’t watch all six of her seasons on As If! or her tween-crap movies, you know her. Maybe you even know how she used to be marked for greatness. How she had wit, she had timing, she had heart. You saw her thirst-trap Vanity Fair cover the month she turned eighteen. In the past few years you saw the lost roles and the flops, or you saw the tabloid shit — the stuff Mae and Dan couldn’t kill—as she spiraled into some sort of slow-motion car crash of the soul.

Red-wine stains on her orange Celine hoodie—another thousand dollars down the drain. But it’s the sunglasses that Mae’s thinking about. Hannah is wearing too-big sunglasses in a dark room. The job is under those glasses.

Hannah’s voice comes out chopped and screwed: “Hey, bitch.

You look absolutely gorge.”

“You mean like big and empty?”

Hannah doesn’t get it. They fake-kiss hello. The sweat coming out of Hannah has a paint-thinner tang. Her body is pumping out toxins any way it can. The hug turns heavy, Hannah leaning into her, beg- ging Mae to take her weight. Mae holds her up the best she can.

“You have Narcan?” Mae asks Shira over Hannah’s shoulder. The assistant nods like yeah. Hannah pushes her way out of the hug.

“Fuck all the way off. Nobody fucks with fent anymore. Not

since Brad.”

Brad Cherry in Mae’s head—a beautiful dead boy spread across a California king mattress. Mae’s first corpse. Mae forgot Hannah had done As If! with Brad back when they were kids, before the rot set in for both of them. She blinks the sight of the dead boy from her mind.

“This is Mae,” Hannah says to the triplets. “She’s a goddamn killer.” “Hannah,” Mae says, pitching her voice just right—threaded with care and compassion, enough to comfort Hannah but not so much that she’d feel the condescension. The rules say handle the client. “Why don’t you take off your sunglasses and tell me why I’m here?”

Hannah takes off her glasses. Her left eye is purple and swollen like a split plum.

Mae keeps the mask on tight. Her face doesn’t flicker. The rules say keep it to yourself. She turns to Shira again.

“What’s her call time?”

“Makeup at four a.m.”

“Shit.”

According to the Story—the one cooked up by Hannah’s team—Hannah’s been rehabbing her life these past six months. The publicists set up redemption-arc interviews with friendlies at the big glossies. They tipped off paps to snap candids of her buying organic juices and vegan wraps at Erewhon. The Story worked. Tomorrow she starts filming on an Oscar-bait indie drama. It’s not the lead, but it’s a good part. If all goes well, the Story can enter its second act: Pop Actress Proves She’s Got Chops.

Her eye fucks up everything.

The movie people will go apeshit when they see Hannah’s eye. They can maybe film around her or fix her eye in post. CGI makeovers are boilerplate for the big stars—contractually obligated digital eye lifts and virtual Botox. But Hannah isn’t big like that. If Hannah’s eye fucks up her first day, if they see it as a symptom of being terminally fucked-up, the producers will shitcan her and bring in whatever next-year’s-model actress they sure as hell already have in the wings.

Mae knows that in the Industry, if a man falls off a cliff, maybe he can climb back up—people will even stick their hands over the side to yank him to safety. But once a woman falls, she’s fallen for good. If she’s clinging to the edge, folk might stomp on her fingers just for the love of the game. Hannah loses this movie and she drops into the void. The rules say protect the client—even from themselves.

The job is keep Hannah’s gig safe.

“Where’s Tonya?” Hannah’s manager.

“Turning tricks on Santa Monica for all I know,” Hannah says. “Bitch won’t call me back.”

“Jonathan?” Her lawyer. “Incommunicado.”

“What about Enrique?” Her features agent. “He said call you guys.”

That plop-plop-plop you hear is the sound of rats hitting water. Hannah’s team has made their call about which way this will go. They’re not going to try explaining her eye to the producers. They’re throwing it to the black-bag team. And Dan threw it to her.

“Hannah, I need to know what happened.” Mae nods toward the bedroom hallway like let’s talk in there. Hannah shakes her head, dismisses the triplets on the couch with a wave.

“What, the walking dead over there? They’re absolutely wrecked anyway. I bet we sound like Charlie Brown’s teacher to them.”

“Okay, then. So thrill me.”

Hannah tells Mae the story in chunks and sprays. She leaves big pieces UNSAID. Mae can stitch it together.

The whisper network calls it yachting. Women get flown overseas to party on boats with rich men—rich as in numbers so big the human brain wasn’t built to understand them. The yachts circuit the globe, chasing bikini weather, staying in international waters: 24/7/365/all the way around the world. The women are the party favors. They used to fly wannabe actresses out of Burbank by the planeload. Rumor is now most of the women are flown in from Eastern Europe—it’s cheaper. Rumor is now flights from LA are more selective. Rumor is now it’s famous faces only, flown out in private jets for six figures a night. It looks like the rumors are true.

Mae knows the rumors are always true. Even the false ones.

Hannah’s trip went like this: a private car to the Santa Monica airport to a private jet to someplace in France to another private hangar, no customs—she didn’t even bring her passport. From that hangar, a fifty-foot walk to a helicopter. Her feet touched French soil for a minute tops. The helicopter took her into international waters. It landed on a support boat—a hundred-foot cruiser that trailed a mega-yacht, carrying helicopters and water scooters and other toys. The support craft housed security, staff, and girls who didn’t make the cut. An antique wood-bodied tender shuttled her over to the three-story mega-yacht, where the client was waiting. There were ten girls already on board. But Hannah was the prize.

She doesn’t say how she got the gig, who set it up, who put it in motion. She tells parts of it—the worst parts—in a baby-doll singsong delivered to Mochi. She laughs it off like no big deal. Maybe she even thinks she means it.

Inside Mae all these things kick up—the horror of it, but also the thrill, the thrill of inside knowledge of this secret world. To see the world the way it really is.

It is sickening. It is electrifying.

“He thought he was slick. He tried to film me . . . like, during. So I threw his phone out the window or whatever.”

“Porthole,” Shira says. Hannah’s eyes fall on her and the girl shrinks down. Mae can see their whole relationship in that one beat—the late-night calls, the endless errands and picky food orders, the browbeatings and insults and weird moments of love. Not many jobs are as demanding or as intimate as Hollywood assistant—and all of them pay better.

“Porthole. Anyhow, I gifted the asshole’s phone to the dolphins. So . . . ” Hannah touches her eye. She stops talking as some memory washes over her. Tears gloss her good eye. She chews the air, makes a face like it tastes bad. For a second it all threatens to become too real. Then Hannah swallows whatever is trying to get out and the moment passes. She smiles that megawatt smile, the one that bought her ticket to the show.

“Is he a name?” Mae asks.

A possible added level of difficulty. “Not here, anyway.”

“Where, then?”

“I don’t know. One of those countries where it’s okay for hairy old fat guys to walk around in a banana hammock.”

Hannah reaches into the center pocket of her hoodie, pulls out a drawstring bag. She dumps it out. A fistful of loose diamonds shines crazy-beautiful in her palm.

“I guess he felt bad about it,” she says, but not like she means it. “These are, like, reparations. How much are they worth?”

“I have no idea. Maybe ask your manager?”

Hannah shakes her head nuh-uh. “Then she’ll want commission.” She shoves the loose diamonds back in her hoodie pocket. “Probably more than I’m making from this movie anyway.”

She makes a noise like someone carrying something very heavy.

She looks up and talks to the ceiling.

“Fucking Eric. Look what you’ve done to me.”

“Speedo guy’s name was Eric?”

“Not him,” Hannah says. “Forget it. You don’t fucking get it.”

Mae’s brain coughs up a name—Eric Algar, creator/showrunner of As If! The man who discovered Hannah and most of the other teen stars in town. Rumors painted him as a major-league creeper. One of a hundred Mae could name if she really sat down and thought about it.

Like her friend Sarah says:

Nobody talks.

But everybody whispers.

They stand there in the silent aftermath of Hannah’s story. Mae clacks her nails on her cell phone. Mochi yip-yip-yips in Hannah’s arms. Mae takes a deep breath like the internet says to. She focuses on the job. The monster on the boat will be untouched by all this, that’s a given—that’s just how the game is played.

“I need fresh air,” she says. “When I come back, I’ll be smart.”

Outside the grotto is golden-hour gorgeous. Mae can hear muffled sex grunts from the cottage on the left. It just adds to the luxe vibe. The headless Buddha is gone. She knew it would be. They can cover up a dead god as quick as anything else.

Mae weighs her options. The rest of Hannah’s team have clearly marked her as already dead. Mae could walk right now and the only person who’d be pissed is Hannah. And if Mae walks, in two days Hannah won’t matter enough to worry about.

She walks through the grotto and up the stairs to the pool. A photo shoot at the water’s edge is grabbing the golden-hour light. The man at its center is so pretty you can feel the pressure of it against your eyeballs when you look at him. People hold cameras, reflective pads to bounce light. Mae looks at a young girl standing there with a plastic bottle of liquid food for the model. When you first start in the business, sometimes your job could be done by an inanimate object, and they want you to know it.

The thought summons ghosts of bad jobs past. It kicks up anger. Mae decides to use it. She decides to save Hannah’s ass just to show them she can do it. Pleasure pulses at the center of her brain. Angry joy is her favorite kind. It makes her feel alive.

She turns the job over in her head. She reviews the first principles of a cover-up that Dan taught her.

Don’t worry about the truth. It’s not that the truth isn’t important. It just doesn’t matter.

A lie that is never believed by anyone can still have power—if it gives people permission to do what they want to do anyway.

Have a bloody glove—the objective correlative, the one real thing you can point to that makes the lies feel solid.

Give them horror or give them heartstrings. Nothing else sticks.

It comes to her all at once.

She walks back to the cottage. She doesn’t even look at the triplets. She pitches her voice to Hannah like this is an order.

“Jump in the shower, bitch. We’re going to make a movie.”

The first time you’re in the room with a star—not just a famous person, but a star—you get it instantly. You cannot take your eyes off them. And under all the sludge and pain, Hannah can still shine.

When they are done shooting in the bedroom—when Hannah nails every line and beat Mae has scripted for her—Mae heads into the main room. The triplets haven’t moved. One of the men has slumped into unconsciousness, a string of drool hanging from his mouth. Mae waves to Shira like come here.

“She’s uploading the video to Instagram. If she’s got something

that will make her sleep, give it to her. She can still get six hours. Get these three out of here. Have them all sign nondisclosure agreements before they leave.”

“How am I supposed to do that?”

Mae grabs her purse from the counter. “Here. I always carry blank ones.”

Mae decides to stay close until the video hits. She walks past the pool—it’s night now and the photo shoot is done. She walks past Bungalow 3, where John Belushi OD’d. She walks down the steps where Jim Morrison cracked his head open in a drunken fall. She crosses the driveway where Helmut Newton lost control of his Cadillac and rammed a wall and died. The ghosts just add to the luxe vibes.

She enters the hotel, goes up the stairs to the lobby. Gary Oldman passes her in a big Quaker hat. She goes to the hostess stand. All the hostesses wear the same shade of rust. They are all the same brand of gorgeous. Mae name-drops Hannah. She sees the holy terror in the hostess’s eyes. It works—there’s a spot open in

the tiny corner bar. She orders a cocktail—something with yuzu and mescal that tastes like delicious leather. Dakota Johnson passes her in a giant faux-fur coat. There’s some floral scent pumped into the air. Sam Rockwell and Walton Goggins sit at a crowded table behind her. Grimes on the stereo—this ingenue voice singing the word violence over and over again. She steals glances at the famous faces stealing glances at her—trying to figure out if she’s someone. She likes feeling like a mystery. Being Schrödinger’s big shot. She lets the hotel’s magic calm her down. She doesn’t think about men on yachts doing whatever they please.

Her phone buzzes in her purse. Dan. No cell phones allowed in the bar. She drops a twenty and a five on the bar. She answers her phone on the move. Dan doesn’t bother with hellos.

“Her fucking dog?” Pure joy in his voice.

“Give them horror or give them heartstrings. Nothing else sticks.

Somebody told me that once.” He laughs.

“So I guess she uploaded it?” she asks.

The video runs about two minutes. Hannah holds Mochi, her sunglasses on, telling a funny story about the little dog needing to take her anxiety medicine—how she hates it, how she always squirms. The story climaxes with a wiggling Mochi headbutting Hannah. Hannah takes off her glasses at just the right moment—the black eye plays like a punch line. She lets Mochi lick her face—all is forgiven. The video plays perfect. Hashtag mochi the bruiser. Hashtag viral as hell.

“The studio already retweeted the video,” he says. “They know a hit when they see it.”

“So she’s still in the picture?” Mae stops in the hotel vestibule. “Cameras start rolling at six a.m. They’ll fix her eye in post. Her

manager called me. Said kudos to you. Said you steered the ship past the rocks.”

The manager didn’t say that. That was how Dan talked. She knows him well. She knows he won’t ask what the real story is, not over the phone.

“Think she’ll make it to the end of the shoot?”

“Imagine me giving a shit,” he says. He laughs. There’s something off about his tone. It makes Mae nervous. They have learned to read each other. Mae knows this conversation could have waited until Monday. She knows it is a pretext for something else. She knows small talk is done, and he’s ready to pivot to his real reason for calling.

“Got plans after work on Monday?” he asks. “Barre class maybe.”

“Come have a drink with me.” Something in the tone raises gooseflesh on her arms.

Dan is her favorite boss she’s ever had. He’s never yelled at her or made her feel stupid or thrown things at her.

And he’s never hit on her.

“A drink?” she says like she’s never heard of them, a pure conversational punt while she scrambles inside.

“The Polo Lounge,” he says. “I’m buying. But keep it QT, okay?” Bad vibes on top of bad vibes. The Polo Lounge, inside the

Beverly Hills Hotel. Drinks at a hotel bar. California king beds an elevator ride away.

“Any reason?”

“I just want to share my grand vision for a brighter future. Namely, yours.” She knows how good he is at lying, at wearing a mask. That she can feel it slipping, even over the phone—it fucks with her. She wants to lie, pretend to remember fake plans. She can’t do it. He’ll know it’s a lie, the same way she knows he’s lying now. It will piss him off. The rules say handle your boss the same way you handle a client.

“Book it,” she says. The rest of the conversation passes in a blur. Her brain scrambles with possibilities. When it ends she makes her way down the hotel driveway to the valet stand. She gives her ticket to a waiting valet. He’s wearing a tuxedo shirt and a full sweat. He sprints. She waits.

A Maybach stops in front of the valet stand. The man who climbs from the back seat is old, great-grandpa old, from the veins on his hand and the spider-wisp of his hair. His frail chest is the color of fish belly under his black silk shirt. A woman a quarter his age climbs out with him—an assistant, not a girlfriend, Mae can tell by the clothes. But he grasps her forearm in just the wrong way, and Mae sees the reaction—the girl is good, she keeps the shiver to her eyes. She watches them head up to the hotel. She wonders about doctors—when they look at someone, can they even see the person anymore? Or do they just see the meat, the guts and veins and tumors? Because when Mae looks at people, all she sees are secrets.

Chapter Two

Chris

MID-WILSHIRE

The Brit’s apartment looks like a picture from a catalog but it stinks like sour laundry. Glass jars full of marbles, antique toys placed just so—all this useless bullshit. Framed posters everywhere, chintzy cheesy slogans in big bold type: live laugh repeat. make your own magic. perspiration leads to inspiration. Ring

lights and tripods everywhere. The Brit’s whole world is just a set. Chris stands in the middle of it all, a clear intruder in this world.

He’s forty-one. He’s huge in a way that used to say offensive lineman—these days he’s trending toward ogre. He’s in a 3XL tracksuit. His hair is uncombed; his skin is pale under a patchy beard.

He is a fist on someone else’s arm.

He surveys the apartment as he shuts the door behind him. A couple of turntables and a mixer on a stand. The kitchen area of the open floor plan is crammed with cardboard boxes—muscle supplements, herbal testosterone boosters, sugar-free energy drinks. Sponcon. The Brit posts pictures of himself with this shit for money.

The front door is cheap and hollow—in his cop days Chris would have kicked it open in one try. Instead he jammed his way in using a credit card. Here’s what being an ex-cop teaches you: There’s all these invisible walls that keep everybody in line. And if you refuse to see them, they just aren’t there anymore. Once you walk through the walls, they never come back up again.

He checks his phone. Patrick texted him ten minutes ago letting him know that the Brit had left the bar in Little Tokyo. Chris figures he’s got another ten minutes before the Brit makes it home. He tosses the apartment to kill time. He searches it the way they taught him in the academy—marking a grid in his mind, working top to bottom. Cop habits die hard.

He finds a salad of pills in a sandwich baggie. He finds an 8-ball of fish-scale cocaine hidden in the couch. He finds a mirror frosted with coke residue. He finds sex toys and coconut oil in the nightstand—and a rubber pussy in the sock drawer. He finds a stack of hundred-dollar bills in a suit pocket in the closet. He pockets the cash, the coke, and the pills.

Cop habits die hard.

He finishes the search. He sits on the couch. He takes out his phone and then puts it away again. He stands up. His bad knee crackles like walkie static.

He hears steps in the hallway. He hears a key drunkenly scraping the lock.

The door opens. In walks this skinny little Brit with cocaine eyes—he’s quasi-famous in a way that means nothing to Chris. He sees Chris. He freezes. Chris can see himself reflected in the kid’s eyes. This troll of a man standing in his apartment.

“The fuck are you, mate?” He tries to brazen it out—his voice doesn’t play along. His face flushes in a way that tells Chris he is a bleeder.

Chris puts off his don’t-run-don’t-yell vibes. The Brit doesn’t do anything at all. His fight-or-flight system is all jammed up.

“Now,” Chris says, “let me tell you where you fucked up.”

Chris moves toward the Brit. The kid doesn’t run. He’s smart enough to know there’s no place to run to. That it will be worse if he does. Chris moves past him and shuts the door.

“You fucked up the same way you all fuck up. You got greedy.”

“You’re the one fucking up, mate. Like maybe you’re as stupid as

you look. Do you know who I am?”

“Yes. Maybe you could have kept selling dirt to the gossip sites forever. But you got greedy.”

The Brit has a lot of D-level famous friends—reality show and Instagram influencer division. He’s been selling secrets on the down low—selling them to whoever is buying. TMZ and Truth or Dare and what’s left of the print tabloids.

Last month the Brit sold a story about B-list actor Patrick DePaulo burning a hole in his septum with coke. Truth or Dare ran it: Patrick DePaulo’s cocaine nose job. Maybe it seemed routine to the Brit. Maybe he didn’t know how bad he was fucking up. Maybe the Brit never got around to asking Patrick what his dad did for a living. Maybe he thought Patrick could afford a Bugatti and a never-ending cocaine buffet off of sporadic sitcom guest spots. Patrick’s daddy, Leonard, owns BlackGuard, LA’s biggest private security firm—surveillance, countersurveillance, protection, and so many other UNSAID services.

BlackGuard subcontracted the job, per usual. Patrick’s daddy didn’t want to use his firm directly when it came to family business. They needed a layer of plausible deniability if the job goes bad. So BlackGuard reached out to Stephen Acker. Acker is a lawyer and another arm of what Chris thinks of as the Beast. Acker reached out to Chris, per usual. Chris is Patrick’s favorite fist.

“You didn’t do your homework about who you were selling out.”

Something connects in the Brit’s head. This gleam Chris can’t quite read in his eyes.

“This is because of Patrick, isn’t it?”

So the Brit does know who Patrick’s daddy is. That means he knew what he was doing. It means whether he knows it on the surface or not, maybe the Brit wanted this to happen. He wanted to go down.

“How we caught you is,” Chris tells the Brit now, “we flushed the toilet.”

“Flushed the fucking toilet?” The Brit sits down on the couch. “We fed all of Patrick’s friends a different piece of fake dirt. Then

we waited to see which turd would come out the pipe. That story

Patrick DePaulo told you about Alana Dupree using in rehab? The one you sold to Truth or Dare two days ago? You were the only person Patrick told that bullshit story to. That’s how we knew you were the rat.”

The Brit slumps forward, cradles his face in his hands. Behind the fear in his eyes, there’s still this weird gleam.

“Flushed the fucking toilet.”

“It’s an old trick,” Chris says. “But it’s a good one.”

Chris should know—it’s the one they used to catch him.

The Brit jams his hand between the couch cushions — he’s feeling for his coke stash. Chris winks at him, pats his pocket where the 8-ball rides. The Brit fish-flops backward.

“A petty fucking thief too, aren’t you? So I sold a fucking story. So what? Everybody runs off at the mouth, why not get paid for it?”

The way he says it makes Chris think of Mae Pruett. What was her line? Nobody talks, but everybody whispers. He pushes her to the back of his mind—that was a long time ago.

“His daddy has soldiers and killers and you’re who he sent, huh?

A member of the fucking goon squad?”

Chris knows it for sure now. Something inside the Brit set his life up for this moment to occur.

Chris has seen the type before. “I’m going to hurt you now.”

“Not my face, huh, mate? I got to film tomorrow.”

Chris nods. He would have left his face alone anyway. Nobody wants to stop the show. Chris moves to the Brit. He picks him up off the couch. He holds him by the shoulders. He knees him in the guts. The Brit pukes air—Chris keeps him on his feet. He lets the Brit catch his breath. His face a mask of pain, that weird gleam in his eyes. Chris knees him again. This time he lets him drop. Chris kneels slow—his bad knee creaks. Chris gets to work. He doesn’t feel anything while he hurts the Brit. He’s not sure the Brit does either.

Chapter Three

Mae

THE WEST HOLLYWOOD HILLS / SIXTH STREET

Mae doesn’t want to go home just yet—she’s got all this stuff burning inside her. She also has a smoke-induced headache.

She turns right out of the Chateau. She crosses the line into the city of West Hollywood. All these party bars and hotels crowd the Strip. The buildings and sky are festooned with billboards for TV shows and movies. Everything is a sequel or a reboot or an adaptation. Everything is an echo of something else. It’s like her friend Sarah says about the Industry: Somebody somewhere catches lightning in a bottle—and all over town people run out and they buy bottles.

She takes a right off Sunset, straight up into the Hills. Sixty seconds later she’s in a different world. Winding roads, impossible houses. Houses that look like kings’ cottages, Bauhaus white boxes, houses that hang from cliffs like suicides. Numbers float in her head. Five point three million. Seven point two million. Four point seven million.

She drives in the hills, deep and high. She opens her moonroof, lets in some air. That firewood scent floats in. She rises toward the top of the hills. Los Angeles sits gleaming below her. Up through the moonroof the sky is flat and black—light pollution kills it.

Under the dead sky the city glows. Like the city reached up into the night and stole the stars for itself.

Twenty years ago. There’s this twelve-year-old girl sitting on a bed in Monett, Missouri. Her eyes are big and green. Her name is Amanda Mae Pruett. She hates it here. She wants to be anywhere else.

Dad takes her shooting sometimes. Guns scare her and thrill her. How they erupt with pure power. She sits on the bed and smells gunpowder on her hands. Her ears ring with the ghosts of gunshots—even with ear protection the noise is intense. She picks up a .22 shell on her desk. How the brass shines. How it carries this potential in it. This power to explode.

I am a bullet, she decides. And I’m going to build a gun that will shoot me out of here.

I am a bullet.

She came to LA about a decade ago, fresh out of Duke. She’d spent her four years there shaping herself into something new. She stripped down this girl named Mandy Mae Pruett, this girl from the Ozarks who made out with wild boys with mean eyes and big trucks. She burned the shitkicker twang from her voice. She sliced off her first name. She took on being called by her middle name the way she took on harsh bangs and cat-eye makeup and skinny emo boyfriends. She sewed new parts onto her to see what would fit.

Her first Industry job was as PA on a single-cam sitcom. The women on the show had a special place, a closet behind the craft services table. “What’s it for?” she’d asked the second AD who showed it to her. “It’s where we go to cry,” the second AD had answered. Mae had laughed at that, thinking how some women were so weak. How some women gave the rest of them a bad name. Until the day number-one-on-the-call-sheet yelled at her for eight minutes straight because she’d got his breakfast order wrong. She got him a new breakfast. Then she’d found her way to the special place. Afterward, she built new walls inside herself.

She moved on. She worked as an assistant for an agent at a Big Four agency—she dodged staplers and ass pats. She learned how to dig her nails into her palms just so while getting screamed at—turning the rage back on herself.

She told herself I am a bullet. And she was one, more and more.

She moved on. She landed an entry-level job at a PR firm. She took to it. She worked under a woman with a cigarette-scarred voice who hated Mae for reasons Mae only dimly understood. The woman liked to put Mae into close contact with very bad men. The woman got this gleam in her eyes, knowing she was sending Mae into all these viper pits. Mae thought about how some people had bad things done to them, and they just couldn’t wait to push that pain onto someone else. She learned to write press releases, learned how to glad-hand reporters, learned how much of our lives is just stories we tell one another, or ourselves.

Dan cold-called her one day. He worked for Mitnick & Associates—LA’s preeminent crisis management firm. He took her to coffee. He pitched her just right: Black-bag PR is a rush. We don’t get the good news out—we keep the bad news in. It’s like James Bond, Hollywood sleaze edition. You’ll go places nobody else in the world gets to go. You’ll know things that nobody else in the world will know. You’ll do ugly things for ugly people—but, hey, the pay is commensurate. You’ll get a peek behind the curtain. It will scare you. But it will buzz you too.

She came aboard. She signed nondisclosure and non-disparagement contracts. She took her vow of silence.

Dan taught her well. She started to think she’d found what she was supposed to do. She thrived. At first she didn’t know why. One day it came in the form of a weird quick flashback: Mae’s family dinner table as a kid, everyone eating in silence, all these crazy UNSAID things. Her dad swallowed his shame. Her mom swallowed her sadness. As a kid Mae learned to read faces and silences. She learned to do things without being told. She learned how to enjoy being angry—and how to use it so it didn’t burn her up. She didn’t know then that this was training. She didn’t know she was being shaped to fight this secret war.

Then came the day, standing over Brad Cherry’s body sprawled across a California king, that she learned for sure that her mantra was true. That when she needed to be, she was cold and hard with a center of fire.

I am a bullet.

Mae gets lost off Benedict Canyon. The roads get narrower.

Mae gets lost inside her head. Dan’s voice plays in a loop. Come have a drink with me.

She’s been at Mitnick & Associates for three years now. Three years running, Dan is the best boss she’s ever had. He’s the first person to see the fight boiling in her and tell her not to hide it—the first person to cry havoc and let her slip. Take scalps, he tells her. Wear an ear necklace.

And he never hits on her.

Maybe she caught the tone wrong. It doesn’t make sense for him to come on to her. Unless it does. Dan fucks around on Jenny—Mae’s known that for years. The shame-hunch of his shoulders as he talks on a cell phone at his desk, his back turned to the door, speaking in whispers. The way he guards his phone sometimes when texts come in.

She turns from Benedict Canyon Road to Cielo Drive. The houses are bigger and farther apart. They hide behind huge gates. The numbers in Mae’s head get bigger. Ten point two million. Twelve point eight million.

She will not sleep with Dan. The cons list is a mile long. His paunch, the smacking way he eats, the fact that he’s married already to a woman Mae knows. The fact that he has kids. The fact that it will hurt her the way it always hurts women in the long run to sleep

with their bosses. Most of all, she won’t because she doesn’t want him like that.

But she does need him as an ally. If this is what she’s afraid it is, she’ll have to handle him. It makes her exhausted just to think about it.

She hits a dead end. She starts a three-point turn to head back down the hill. Her headlights paint a huge wooden gate built into a stone wall. Something clicks for her. Cielo Drive—the Manson murders. Sharon Tate and her friends died bad right here. Well, both here and not here. They tore down the death house a few years back and built this mansion. It’s the same piece of land, but they gave it a new address. They hid the ghosts the best they could. Mae sympathizes. Hiding ghosts is her job too.

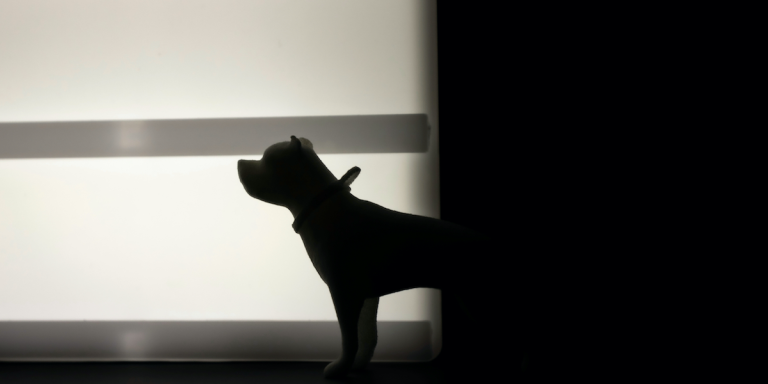

Mae opens the door to her place. Mandy runs to her overjoyed. She’s the ugliest dog in the world—this pony-keg mix of bulldog and who knows what, just wrinkles and sad eyes and farts. Mae loves her big and loves her fierce.

She’d gotten her last year, after a bad day of doing bad things. One of those days when she had to take off her glasses before looking in the mirror, to make herself blurry, to hide herself from herself.

Mandy had some other name at the shelter, but Mae ignored it. Mae already had a name to spare. She looked at this ugly happy stinky loving girl and she decided to call her Mandy—the first name that Mae had cast aside so many years ago. She gave this sweet innocent thing her childhood name and pampered and loved her and kept her safe.

The rules say never think too hard about whys.

Chapter Four

Chris

KOREATOWN

Neon lights the night. A cartoon octopus in a chef’s hat winks at Chris from a restaurant sign. A Catholic church advertises Mass

in five languages. Chris passes a side-street tent village, doubled in size from last month. Beware the Bum Bomber.

From the Brit’s apartment to Koreatown, thirty minutes of bad traffic. Chris was born and raised in Simi Valley—SoCal suburban Copland. Chris moved to Koreatown after he got tossed from the sheriff’s department. Chris likes living someplace where he is an outsider. It feels honest to him.

He rolls down the window—grilled-meat smells float on the air. KBBQ, halal kebab joints, an al pastor street vendor. Chris is caught in a weird traffic snarl. A K-pop boy band is getting towed in a fifties convertible with a camera on the hood. They lip-sync to bass-heavy playback. A teenage girl on the sidewalk sees them. She Beatlemania-shrieks. Chris rolls up the window, toggles on some music. Nipsey Hussle—one of LA’s newest ghosts.

Pain shoots up Chris’s left arm. A sudden fist in his chest.

Not a heart attack, he tells himself.

He chews baby aspirin dry. The bile-sour taste fills his mouth. The fist in his chest relaxes. The first time he had chest pains he went to the ER. He spent three hours in the waiting room next to a moaning woman with a leaky colostomy bag. Now he doesn’t bother. It’s never a heart attack—until it is.

The music dies—a call coming in over Bluetooth. Acker.

“Tell me everything,” Acker says. He doesn’t mean it. Acker doesn’t want anything said out loud.

“We’re happy,” Chris says.

“Of course we are, baby. You’re the best.” Acker is so up front with his bullshit it almost counts as honesty. “BlackGuard wants you to come in on Monday. Standard debrief.”

“Yeah, sure.”

“This is good for you,” Acker says. “A solid like this for the big man’s son.”

Chris clicks off. Horns in cacophony bring his mind back to the road. The truck towing the boy band is stuck—a man wearing nothing but newspapers and street grime stands in the middle of Wilshire. His eyes burn with holy truth. He’s delivering some sort of sermon. Maybe it’s the word of God—the horns drown it all out anyway.

His apartment is in Koreatown just south of Wilshire. It’s in a grand old building that must have really been something once. The building has an old neon sign proclaiming it the ambassador. The apartments are big with hardwood floors and old limestone walls.

Chris’s place is messy in that way that lets you know nobody else has been here in a very long time. He hides the cash he took from the Brit—he eyeballs it at about three grand. He hides the coke. He’ll pass it along to Patrick DePaulo to curry favor next time he sees him. Chris won’t mess with coke, not anymore. Coke was for the old days, the warrior-king days.

He eats pork katsu curry from a strip mall nearby. It’s delicious and he barely tastes it at all. He watches old sitcoms. He has curry burps. He tries to find a name for what he is feeling, and when that doesn’t work, he tries to feel nothing at all. He picks through the pills he stole from the Brit. He IDs a Demerol. He pops it. It kicks in quick. He settles back in his chair, drifts into some sort of warm half world. He cues up another sitcom. He looks at the scraped and torn knuckles. He flexes his hands—the pain pops from the joints in a distant way. The scene with the Brit already feeling like it happened to somebody else—or maybe to no one at all.

He remembers the homeless preacher and his crazy eyes. His mouth moving with holy scripture. Chris tries to imagine what God would say to him. But when he tries to think of the words all he can hear is car horns.

Discover the Book

Welcome to Mae Pruett’s Los Angeles, where “Nobody talks. But everybody whispers.” As a “black-bag” publicist tasked not with letting the good news out but keeping the bad news in, Mae works for one of LA’s most powerful and sought-after crisis PR firms, at the center of a sprawling web of lawyers, PR flaks, and private security firms she calls “The Beast.” They protect the rich and powerful and depraved by any means necessary.

After her boss is gunned down in front of the Beverly Hills Hotel in a random attack, Mae takes it upon herself to investigate and runs headfirst into The Beast’s lawless machinations and the twisted systems it exists to perpetuate. It takes her on a roving neon joyride through a Los Angeles full of influencers pumped full of pills and fillers; sprawling mansions footsteps away from sprawling homeless encampments; crooked cops and mysterious wrecking crews in the middle of the night.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next