The Literary Appeal of Florence Nightingale

Lytton Strachey first drew my attention to Florence Nightingale through his portrait of her in Eminent Victorians, published in 1918. I was doing research for my first novel, The Darwin Affair, at the time. Here was an individual who by her efforts changed the way the world thought about women in medicine (and in the miliary, and in society). I hoped to find a way to make her path cross with my fictional version of a real London policeman, Inspector Charles Field. I tried to write her into The Darwin Affair but she wouldn’t fit: her stature required a platform of its own. But now, with the publication of The Nightingale Affair, that hope has been fulfilled. As with my earlier book, I have used historical figures to make a fiction; I have created events for them that never happened; I have put words into their mouths that were never there. Knowing Florence Nightingale as I have come to know her, and loving her as I do, I am certain of one thing: she would have hated my book.

Florence was serious. She was not fanciful; she was not for the faint of heart. When she said that God spoke to her, she didn’t mean in a general, ephemeral way. She meant specifically, God to Florence, on four specific occasions in her life.

She was born into a family of great wealth and position, with grand country houses north and south, and of course a London town house. Her doting parents took their two daughters on extended European tours. Their mother prepared them for their debuts into society, which, it was presumed, would lead to marriages to suitable young gentlemen of equal wealth and position.

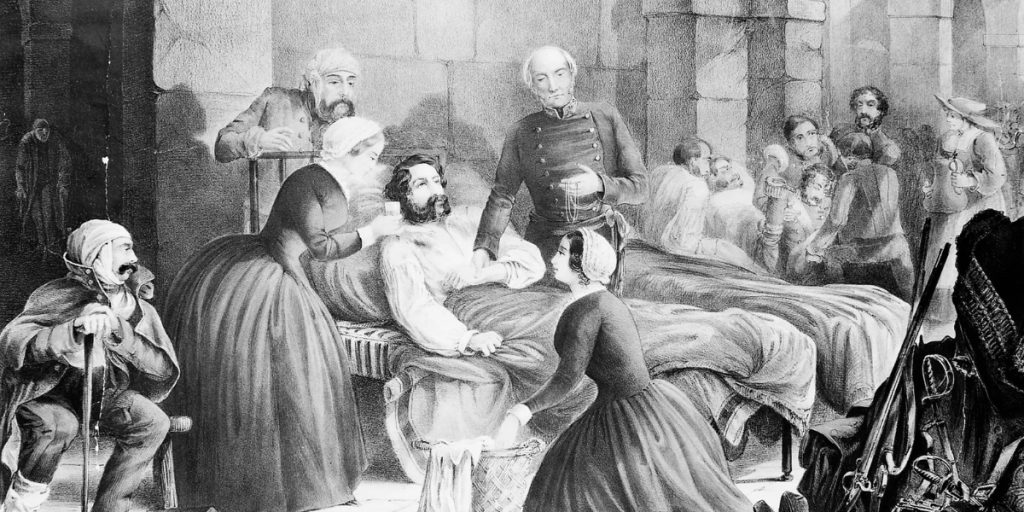

But all along, there was an irritant in the oyster. Florence, from an early age and with growing insistence, wanted to work. This in itself was unheard of for such a young woman. But to her mother’s horror and her father’s sorrow, she wanted to work . . . as a nurse. It’s hard for us to imagine today what that meant in that era, when the legs of pianos and tables were kept modestly covered because they represented body parts, when people retired at night rather than going to bed. Male nurses were for male patients. Female patients could be looked after by female relatives or midwives. A female nurse, caring for male patients? This would entail exposure. Nudity. And, of course, assistance with those chamber pots.

Female nurses were tramps, obviously. Slovenly, unreliable, drunk. Charles Dickens created the ultimate such creature in Sarah Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit. Mrs. Gamp is hilarious as a character, but you wouldn’t want her tending you in real life, and you certainly wouldn’t want her as a daughter.

Miss Florence, however, was adamant. Reluctantly, her parents granted her permission to study for a time the nursing activities of a German hospital. There she saw disciplined women caring for male and female patients alike. The nurses were entirely sober and serious about their work. She learned from them principles of patient hygiene that were ahead of their day, and that remained with Florence throughout her life. To her parents’ dismay, the time she spent in the Krankenhaus did not get the God-dictated vision of herself as a nurse out of her system.

Not even the repeated, earnest proposals of marriage from a perfectly suitable, handsome young man with strong social justice convictions could do that, although for Florence it was a serious struggle. Finally, she turned him down. And still, her parents refused to let her pursue her passion.

The depression into which she fell was profound. She withdrew from her family and from society altogether. Her journal entries were dark. She saw no hope. The elder Nightingales, who were, after all, loving, devoted parents, finally gave in. Florence would become the matron of a genteel home for sick or elderly governesses. It was presided over by a female board of directors who were the Nightingales’ social equals. Surely now Miss Nightingale would be satisfied.

But then, in 1853, war was declared. England and France would join forces to stop Russia from snatching the Crimean Peninsula from the Ottoman Empire. (Ring any horrific bells?) British troops marched off to the acclaim of their nation and their queen. And, for the first time in history, the war was covered in the press by reporters who were actually on the scene, on the front lines. Thanks in part to the newly invented telegraph, the public would follow the events of the great conflict almost as they happened.

And so it was that news of appalling conditions at the British hospital in Turkey, commandeered for the troops, was proclaimed in the Times of London. Wounded and sick British soldiers were dying in shocking numbers. The Barracks Hospital at Scutari had a mortality rate almost rivaling that of the battlefield.

Florence, who knew everybody, wrote a letter to her good friend Sir Sidney Herbert, Secretary at War. She proposed enlisting thirty or so female nurses and sailing out with them to the Crimea. At the same time, Sir Sidney wrote a letter of his own to his dear friend Miss Nightingale. Would she be willing to lead a contingent of nurses to the hospital at Scutari?

Their letters crossed in the mail.

What shocked me most in studying this history was the intensity of hatred with which Nightingale and her nurses were met by the army medical men who led the flailing Barracks Hospital. And hatred is not too strong a word. The head of the hospital quickly started calling Nightingale “the Petticoat Imperieuse.” Letters were written to London accusing her of “an ambitious struggling after power.” When a couple of front-line reporters sent home word in the Times of the speed with which Nightingale and her women labored to correct the dire conditions, to separate the living from the dead, to get patients up off the floors and into beds, to get clean linens for those beds, to scour the filthy wards and, yes, to clear the overflowing cesspits, the men in charge were even more enraged. Some of them countered Nightingale’s requests for supplies and aid passively, by ignoring them. Others took more direct actions to foil her mission and to get her and her women back home where they belonged. No one tried to murder the women, unless one puts the attempts to starve them out of the Crimea into that category. The dreadful crimes in The Nightingale Affair, those committed during the war and those that erupted in London a dozen years later, are products of my own fiction.

But I wonder if it’s such a stretch to imagine murder on a sliding scale with implacable hatred? My fictional Nightingale says this to my fictional Inspector:

“These dreadful crimes, Mr. Field, are aimed at women. And every crime of this nature is another mark against us nurses, as the world tallies it. Someone is not only satisfying a personal demon but trying to denigrate our work here as well, which is seen as an invasion of a male-only domain. This criminal, whoever he may be, is likely a madman. But he has many unknowing allies among sane, law-abiding upstanding Christian males, Mr. Field. That is what we’re up against.”

Lytton Strachey accused Nightingale of being less than agreeable. Was this just a male’s response to a woman who went against the grain, who stepped on toes to achieve her ends? Not entirely, I think. Florence enlisted aid from family members and friends, and a number of them responded wholeheartedly, at real sacrifice to themselves. Some went out with her to the beleaguered hospital and helped her turn it around; others assisted her in later life, as she continued her struggle to revolutionize medical care both in the army and the civilian sphere. But if any returned to tend to their own lives, Florence could turn on them in a fury, condemning them for lack of loyalty. With her adversaries in the war she was circumspect; she kept her feelings to herself and pursued her goals quietly rather than through confrontation. She knew the dangers of crossing the male ego. But among allies, male and female, she unloosed her rage. Poor Sir Sidney Herbert, who had commissioned her in the first place, often bore the brunt of her anger, and often it was unjustified.

Even so, I found her possessed of a quiet, playful wit that she shared with trusted friends. She cared for her nurses, and admired the courage they showed in following her blindly into a world of hardships they could not have imagined before setting sail. And her love for the common British soldier is undeniable.

Florence Nightingale had a vision. She had a directive from God; considerations of fairness were insignificant by comparison. She ducked the accolades society tried to award her when she returned at the war’s end. She used her wealth to buy a town house and disappeared, physically, from the world. But she became more active than ever in seeking to break through the hidebound, male-dominated realm of health care to cause real reform. The handbook she wrote on nursing is still used in nursing education to this day. The official report on the conduct, and misconduct, of the British hospitals during the Crimean War helped begin a movement for lasting reform in health care within the military and the public at large.

Florence Nightingale wrote much of that document herself, based on her findings and backed up by the voluminous statistics she kept. However, when it was published, the report bore the names of its authors—minus one. Miss Nightingale’s name was not there. She was, after all, only a woman.

Discover the Book

Case closed. Or is it?

Twelve years later, back in London, amid the turmoil surrounding the expansion of voting rights, women again start turning up dead, their mouths covered by that telltale embroidered rose. Did Field suspect the wrong man before, or is he dealing with a deviant copycat? Either way, he must race against time to stop the killer before more bodies are discovered, and before his own family gets pulled into danger. Populated by real figures of the day, from Benjamin Disraeli to novelist Wilkie Collins to, of course, Florence Nightingale herself, and steeped in historical details of 1860s London, The Nightingale Affair plays out against a backdrop of a rapidly changing society. Most of all, it is a pure reading delight, offering shocks, unforgettably vivid scenes, and surprising twists.

Field’s investigation soon exposes a shocking conspiracy: the publication of Charles Darwin’s controversial On the Origin of Species has set off a string of terrible crimes—murder, arson, kidnapping. Witnesses describe a shadowy figure with lifeless, coal-black eyes. As the investigation takes Field from the dangerous alleyways of London to the hallowed halls of Oxford, the list of possible conspirators grows, and the body count escalates. And as he edges closer to the dastardly madman called the Chorister, he uncovers dark secrets that were meant to remain forever hidden.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use