Metafiction and the Whodunit Mystery Novel

Metafiction is fiction which openly acknowledges that thing the reader already knows—that what they are reading isn’t real. They know it isn’t real because they selected their novel from the fiction section of the bookshop. Some fiction even has ‘A Novel’ right there on the front cover. So, acknowledging that the reader is reading fiction should not be in any way subversive. And yet it almost always is.

Metafiction feels subversive because fiction feels real. Neuroscientists have studied the effects of fiction on the brain and have discovered that the brain cannot tell the difference between, for example, smelling cinnamon or reading the word ‘cinnamon’. The olfactory sensors of the brain light up in the same way for both. Less scientifically, it may be observed that reading suspense fiction makes our hearts race and reading romance fiction makes our eyes leak just as if they were happening to us in real life.

The psychoanalytic literary critic, Norman N Holland, argues that knowing that fiction is not real allows the reader to believe fiction more fully than real life. We can read suspense fiction without having to worry about our personal safety, and romance fiction without our feelings being hurt. And so, we believe that what we read is true, while knowing it is not.

Metafiction plays with these boundaries between knowing and not knowing. Between belief and disbelief. And the natural home of metafiction is the whodunit.

There is usually a point in an Ellery Queen novel where the author addresses the reader. In The Roman Hat Mystery, the very first Ellery Queen story, he says: ‘The alert student of mystery tales, now being in possession of all the pertinent facts, should at this stage of the story have reached definite conclusions on the questions propounded.’, before adding that the solution can now be reached through a series of ‘logical deductions and psychological observations’.

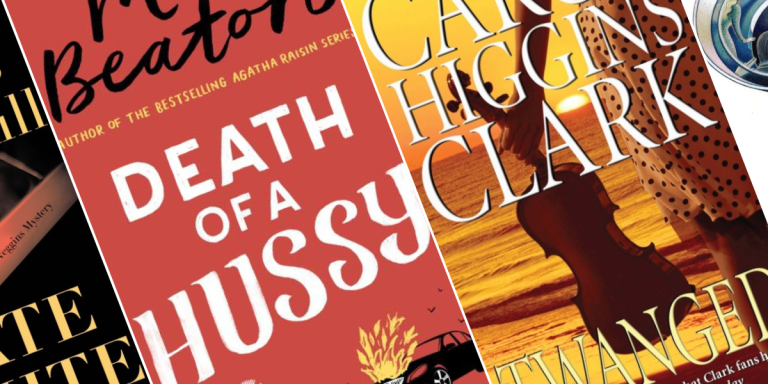

The whodunit is a game played between the reader and the author. The author tries to misdirect the reader’s attention while he hides the clues. They entice the reader with juicy red herrings. They throw in conflicting testimonies from suspects who are all hiding something from the detective (and from the reader, too, of course). They may, like Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee, adopt the name of the literary detective and become Ellery Queen. Authors may refer to themselves or their books indirectly in the text, as Agatha Christie does in The Body in the Library. They may appear in the book in disguise. The character of Ariadne Oliver is said to be a disguised self-insert by Christie. Oliver is a whodunit writer who often expresses her frustration with her friend Hercule Poirot – frustrations which Christie was said to share. Sometimes it is hard to know which is the character and which is the writer. In Cards on the Table, Ariadne Oliver discusses her book, The Body in the Library. Christie did not write her own Body in the Library until six years after Ariadne Oliver discussed hers.

The author may even insert themselves into their story under their own name and try and beat their own detective, and their reader, to the solution, as Anthony Horowitz brilliantly does in The Word is Murder, where the detective, Daniel Hawthorne, enlists a reluctant, and often grumpy, Horowitz to write up his cases. Horowitz believes that, as a detective story writer, he must have the skills to solve a case himself. The series is currently five books in and, so far, Anthony Horowitz has shown all the detecting ability of Dr Watson. Which is to say, none at all.

The Golden Age detective writer Ronald Knox said that the purpose of the Watson was give the reader a sparring partner that they could actually beat: “‘I may have been a fool,’ he says to himself as he puts the book down, ‘but at least I wasn’t such a doddering fool as poor old Watson.’”

Of course, Horowitz, as the creator of Daniel Hawthorne, and the author of the books, is responsible for the brilliance of his Holmes every bit as much as the doddering foolishness of the Watson he has created and given his own name to.

And the reader will know this.

Classic whodunits are not afraid to let the reader know that the story isn’t real. The victim, usually a villain or a fool, is killed off-stage or killed quickly, even comically, so that the reader need not trouble themselves by feeling sorry for them. The suspects are limited to a named handful of people, few enough for the reader to keep track of them all. Every suspect has a motive and any motive will do. And the clues are hidden throughout the book just so the reader can have the fun of searching them all out in a grand kind of treasure hunt.

Whodunits are metafiction, because whodunits are a game. The game is the most important aspect of the whodunit. And The Game is Murder!

Discover the Author

Hazell Ward lives in Wrexham in North Wales, where she spent many years as an adult education teacher before going on to work for a charitable organization as a mentor to young people. She completed an MA in creative writing at Manchester Metropolitan University and is currently juggling finishing her PhD with writing her second novel. She was short-listed for the Margery Allingham Short Mystery Competition in 2021 and won the Crime Writer’s Association Short Story Dagger in 2023 for her story “Cast a Long Shadow,” published by Honno Press. The Game Is Murder is her debut novel.

If you agree to play the role of the Great Detective, you must undertake to provide a complete solution to the case. A verdict is not enough. We need to know who did it, how they did it, and why. Are you ready? Can you solve the ultimate murder mystery–and catch a killer?

A word of warning: Unsolved mysteries are not permitted. . . .

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use