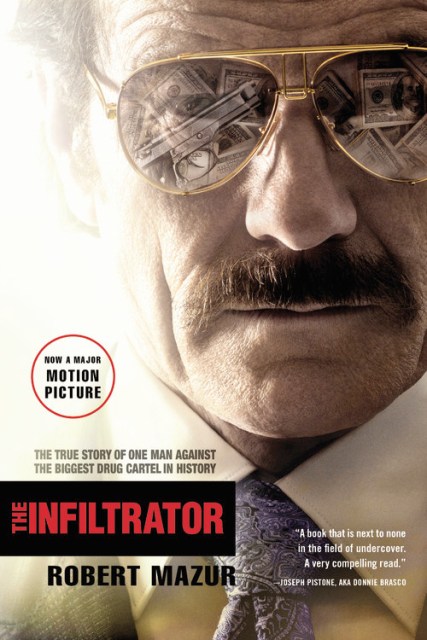

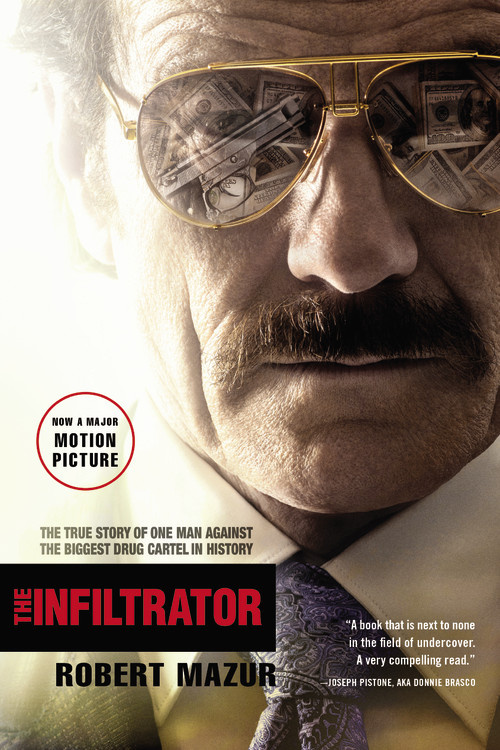

The Infiltrator

The True Story of One Man Against the Biggest Drug Cartel in History

Contributors

By Robert Mazur

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 21, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The electrifying true story of Robert Mazur’s life as an undercover agent who infiltrated one of the world’s largest drug cartels by posing as a high-level money launderer — the inspiration for the major motion picture The Infiltrator.

Robert Mazur spent years undercover infiltrating the Medellín Cartel’s criminal hierarchy. The dirty bankers and businessmen he befriended — some of whom still shape power across the globe — knew him as Bob Musella, a wealthy, mob-connected big shot living the good life. Together they partied in $1,000-per-night hotel suites, drank bottles of the world’s finest champagne, drove Rolls-Royce convertibles, and flew in private jets. But under Mazur’s Armani suits and in his Renwick briefcase, recorders whirred silently, capturing the damning evidence of their crimes.

The Infiltrator is the story of how Mazur helped bring down the unscrupulous bankers who manipulated complex international finance systems to serve drug lords, corrupt politicians, tax cheats, and terrorists. It is a shocking chronicle of the rise and fall of one of the biggest and most intricate money-laundering operation of all time-an enterprise that cleaned and moved hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Filled with dangerous lies, near misses, and harrowing escapes, The Infiltrator is as bracing and explosive as the greatest fiction thrillers — only it’s all true.

Robert Mazur spent years undercover infiltrating the Medellín Cartel’s criminal hierarchy. The dirty bankers and businessmen he befriended — some of whom still shape power across the globe — knew him as Bob Musella, a wealthy, mob-connected big shot living the good life. Together they partied in $1,000-per-night hotel suites, drank bottles of the world’s finest champagne, drove Rolls-Royce convertibles, and flew in private jets. But under Mazur’s Armani suits and in his Renwick briefcase, recorders whirred silently, capturing the damning evidence of their crimes.

The Infiltrator is the story of how Mazur helped bring down the unscrupulous bankers who manipulated complex international finance systems to serve drug lords, corrupt politicians, tax cheats, and terrorists. It is a shocking chronicle of the rise and fall of one of the biggest and most intricate money-laundering operation of all time-an enterprise that cleaned and moved hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Filled with dangerous lies, near misses, and harrowing escapes, The Infiltrator is as bracing and explosive as the greatest fiction thrillers — only it’s all true.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 21, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316077521

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use