Promotion

Use MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

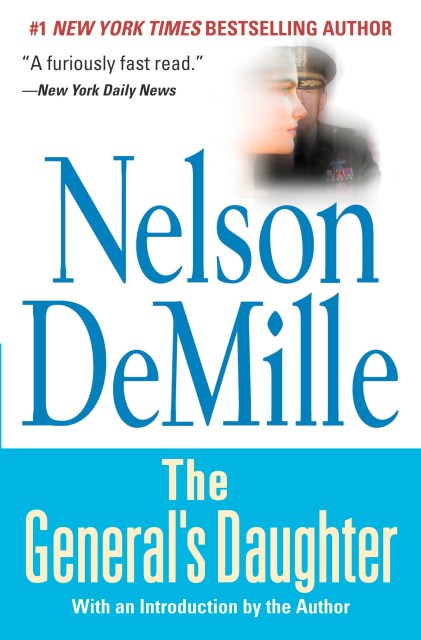

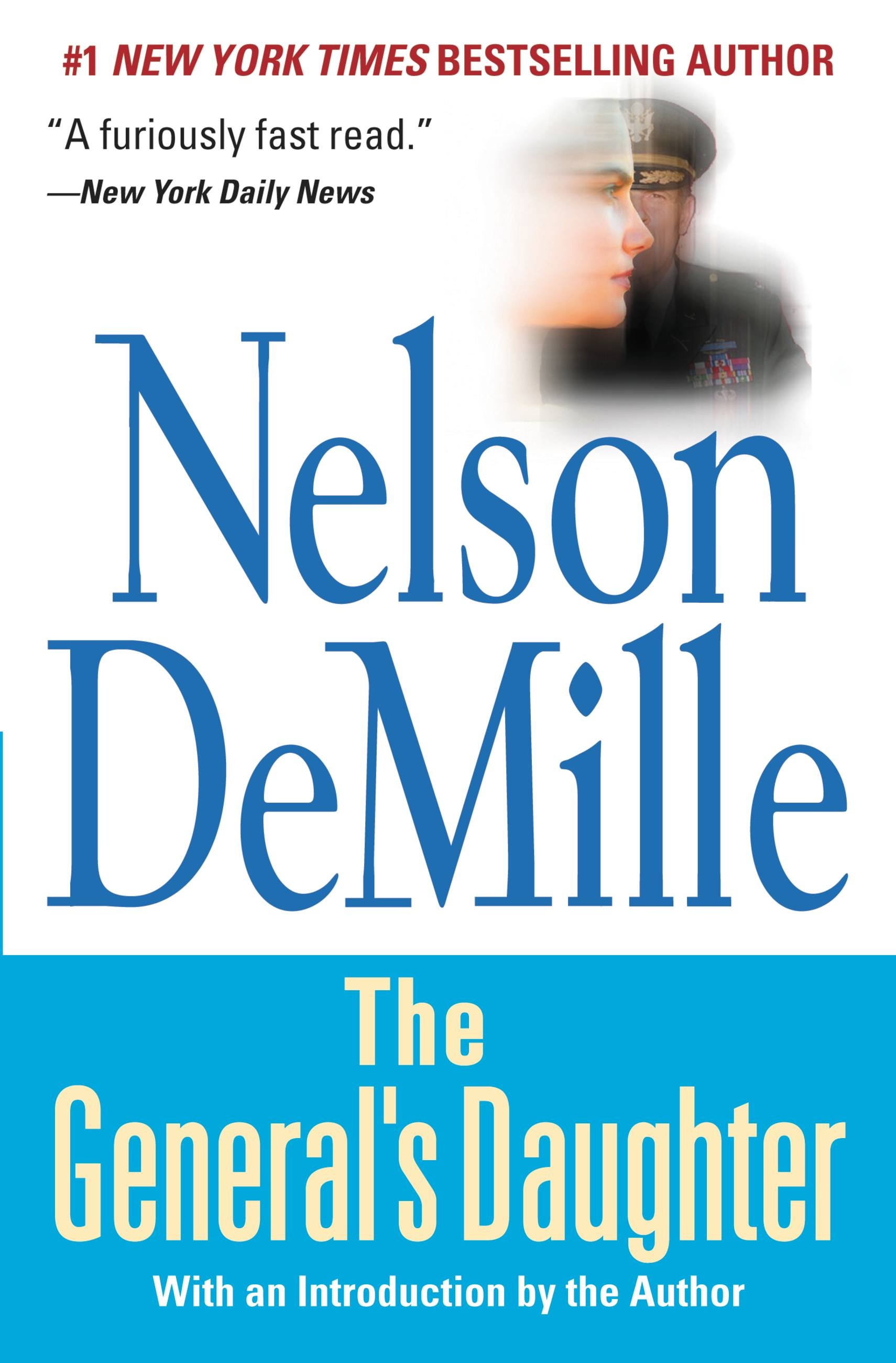

The General's Daughter

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Mass Market $8.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 1, 2002. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When a professional military woman with a pristine reputation is found raped and murdered, a preliminary search turns up certain paraphernalia, and sex toys that point to a scandal of major proportions, The chief investigator is reluctant to take the case when he learns that his partner will be a woman with whom he had a tempestuous affair and an unpleasant parting. But duty calls and intrigue begins when they learn that several top-level people may have been involved with the “golden girl” – and many have wanted her dead.

It’s Nelson DeMille at his best – exciting, suspenseful and highly provocative.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 1, 2002

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446679107

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use