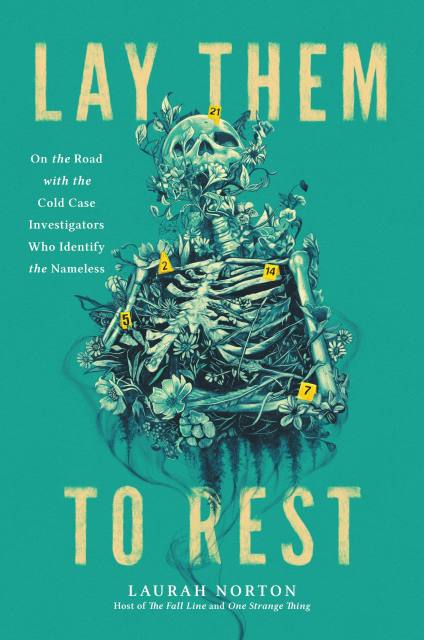

Lay Them to Rest

On the Road with the Cold Case Investigators Who Identify the Nameless

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 17, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Take a fascinating deep dive into the dark world of forensic science as experts team up to solve the identity of an unknown woman by exploring the rapidly evolving techniques being used to break the most notorious cold cases.

Fans of true crime shows like CSI, NCIS, Criminal Minds, and Law and Order know that when it comes to “getting the bad guy” behind bars, your best chance of success boils down to the strength of your evidence—and the forensic science used to obtain it. Beyond the silver screen, forensic science has been used for decades to help solve even the most tough-to-crack cases. In 2018, the accused Golden State Killer, Joseph DeAngelo, was finally apprehended after a decades-long investigation thanks to a very recent technique called forensic genealogy, which has since led to the closure of hundreds of cold cases, bringing long-awaited justice to victims and families alike. But when it comes to solving these incredibly difficult cases, forensic genealogy is just the tip of the iceberg—and many readers have no idea just how far down that iceberg goes.For Laurah Norton, forensic science was always more of a passion than anything else. But after learning about a mishandled 1990s cold case involving missing twins, she was spurred to action, eventually creating a massively popular podcast and building a platform that helped bring widespread attention and resources to the case. LAY THEM TO REST builds on Laurah’s fascination with these investigations, introducing readers to the history and evolution of forensic science, from the death masks used in Ancient Rome to the 3-D facial reconstruction technology used today. Incorporating the stories of real-life John & Jane Does from around the world, Laurah also examines how changing identification methods have helped solve the most iconic cold cases. Along the way readers will also get to see Laurah solve a case in real time with forensic anthropologist Dr. Amy Michael, as they try to determine the identity of “Ina” Jane Doe, a woman whose head was found in a brush in an Illinois park in 1993.

More than just a chronicle of the history of forensics, LAY THEM TO REST is also a celebration of the growing field of experts, forensic artists, and anthropologists (many of whom Laurah talks to in the book), who work tirelessly to bring closure to these unsolved cases. And of course, this book asks why some cases go unsolved, highlighting the “missing missing,” the sex workers, undocumented, the cases that so desperately need our attention, but so rarely get it.

Engrossing, informative, heartbreaking, and hopeful, LAY THEM TO REST is a deep dive into the world of forensic science, showing readers how far we’ve come in cracking cases and catching killers, and illuminating just how far we have yet to go.

-

Oprah Daily, “Books That Every True Crime Obsessive Needs to Read”

Book Riot, "THE BEST NEW BOOK RELEASES" and "14 New Mysteries, Thrillers, True Crime for October 2023 Sleuthing"

Publishers Weekly, "New True Crime Books" -

"In thrilling (and digestible) detail, Norton reveals the cutting-edge science behind 'every attempt to connect her to the woman she’d been in life, and to the people who never stopped looking for her'... Rather than simply scratching a morbid itch, obsessing over these sorts of true crime stories can lead to true justice. A win in anyone’s book."Oprah Daily

-

"Lay Them to Rest... will keep readers of all kinds on the edge of their seats wondering just how painstakingly slow and often difficult the process of identifying John and Jane Does truly is as she follows investigators and scientists like biological anthropologist Dr. Amy Michael as they dive into cases like that of "Ina" Jane Doe. Heavy on science, but in a very accessible way, the book manages to educate and entertain while also showing that the reality of forensic anthropology is a whole lot different from an episode of Bones."Shondaland

-

"Beautifully written."Defrosting Cold Cases

-

"Absolutely gripping... Norton’s commitment to her subject matter is contagious. She writes with such passion that readers will get caught up in the stories of otherwise overlooked and nameless victims, become invested in the outcomes of the cases she’s discussing, and share a sense of triumph when breakthroughs finally come. A fine and necessary addition to any nonfiction-crime aficionado’s bookshelf, and to any library’s true crime section."Booklist

-

“A comprehensive study of the difficult task of figuring out the identities of faceless victims of violent crime…"Kirkus

-

"True-crime podcast listeners will take the invitation to tag along on a challenging case."Library Journal

-

“Part murder mystery, part master class in forensics, Laurah Norton’s Lay Them to Rest leads readers through a twisty personal investigation complete with a startling reckoning. Norton seamlessly transplants her passion for justice from her fantastic podcast to the narrative page—a must-read for true crime fanatics.”Kate Winkler Dawson, American Sherlock: Murder, Forensics, and the Birth of American CSI

-

“Laurah Norton’s Lay Them to Rest is a beautifully woven mystery that captivates the reader from the first page as you root for her to solve the case. Norton’s expertise and her dedication to the victim shine through. This book and Norton’s work is the good in true crime that everyone should pay attention to.”Sarah Turney, Victim Advocate and CEO, Voices for Justice Media

-

“Rarely do readers of true crime get something as fresh and engaging as Laurah Norton’s Lay Them to Rest. Norton’s passion and empathy shine in this candid and personal account of her work with unidentified persons. Her admiration of those who share her passion gives an intimate look behind the scenes of complex investigations. She effortlessly guides readers—with the help of industry experts—without losing focus on the people at the heart of the case. Lay Them to Rest leaves a lasting impression even after the final page is turned.”Kristen Seavey, Victim’s Advocate and Creator, Murder, She Told podcast

-

“In Lay Them to Rest, Laurah Norton not only gives a masterclass on ethical research and reporting, but a humanizing and empathetic look at some of the most marginalized and overlooked victims: the nameless. Lay Them to Rest gives readers an unwaveringly honest look at what true crime actually is and entails; Laurah’s journey is equal parts obsessive and compassionate, exhilarating and patient, driven and human. I’ve never seen a more honest and comprehensive look at an investigation, which never shies away from juggling advocacy, working with law enforcement, and managing personal attachments. Every consumer of true-crime media should be required to read this work.”Josh Hallmark, Creator, True Crime Bullsh**

-

“Laurah Norton pulls back the curtain on forensic sciences and allows readers easy access and understanding of the important work being done in this field.”Nina Innsted, Host of Already Gone, They Walk Among America, Up and Vanished: The Trial of Ryan Duke, and Missing-Persons Advocate

-

“In Lay Them to Rest, Laurah Norton immerses readers in a captivating exploration of true crime’s true essence: the victims. Laurah takes us on a gripping journey as she illuminates the mystery surrounding ‘Ina Jane Doe,’ delving into the relentless collaborative efforts of agencies, forensic scientists, and experts to unveil her identity, honor her story, and provide the closure she deserves.”Melissa Rice, Co-creator, Moms and Mysteries, and Board member of The Bridegan Foundation

-

“Laurah Norton’s beautiful and compelling narrative brings the reader along as the team cracks a cold case, all while giving us a hard look at the science—and art—of how they do it. With deep research and surprising moments of humor, this book has a place on the shelf of everyone who has ever wondered what it takes to solve a mystery.”Charlie Worroll, Creator, Crimelines and Co-Creator, Crimelines and Consequences

-

“Laurah Norton takes us behind the scenes as she helps to solve a cold case in real time, skillfully breaking down layers of complexity in a way everyday readers can understand. A gripping must-read for anyone interested in true crime.”Kristi Lee, Creator, Canadian True Crime

- On Sale

- Oct 17, 2023

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306828805

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use