Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters save 20% off your next purchase. Shop now.

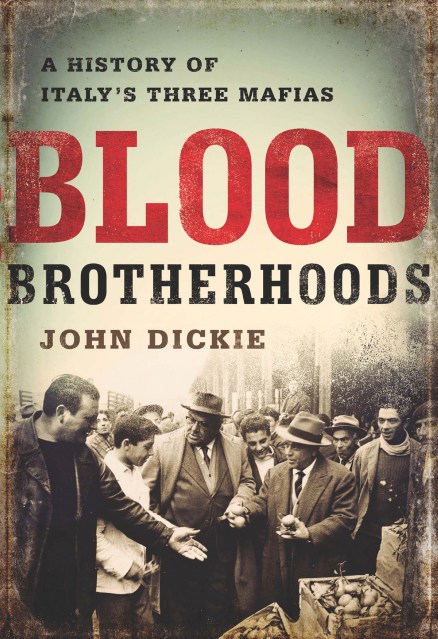

Blood Brotherhoods

A History of Italy’s Three Mafias

Contributors

By John Dickie

Formats and Prices

Price

$56.00Price

$71.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $56.00 $71.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 22, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Sicilian mafia, known as Cosa Nostra, is far from being Italy’s only dangerous criminal fraternity. The country hosts two other major mafias: the camorra from Naples; and, from the poor and isolated region of Calabria, the mysterious ‘ndrangheta, which has now risen to become the most powerful mob group active today.

Since they emerged, the mafias have all corrupted Italy’s institutions, drastically curtailed the life-chances of its citizens, evaded justice, and set up their own self-interested meddling as an alternative to the courts. Yet each of these brotherhoods has its own methods, its own dark rituals, its own style of ferocity. Each is uniquely adapted to corrupt and exploit its own specific environment, as it collaborates with, learns from, and goes to war with the other mafias.

Today, the shadow of organized crime hangs over a country racked by debt, political paralysis, and widespread corruption. The ‘ndrangheta controls much of Europe’s wholesale cocaine trade and, by some estimates, 3 percent of Italy’s total GDP. Blood Brotherhoods traces the origins of this national malaise back to Italy’s roots as a united country in the nineteenth century, and shows how political violence incubated underworld sects among the lemon groves of Palermo, the fetid slums of Naples, and the harsh mountain villages of Calabria.

Blood Brotherhoods is a book of breathtaking ambition, tracing for the first time the interlocking story of all three mafias from their origins to the present day. John Dickie is recognized in Italy as one of the foremost historians of organized crime. In these pages, he blends archival detective work, passionate narrative, and shrewd analysis to bring a unique criminal ecosystem — and the three terrifying criminal brotherhoods that have evolved within it — to life on the page.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 22, 2014

- Page Count

- 800 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610394277

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use