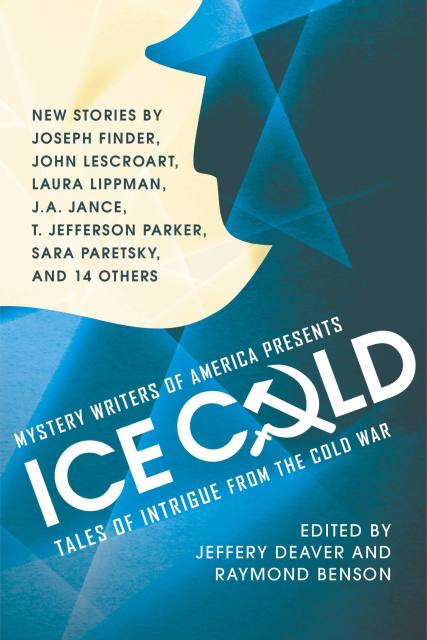

Mystery Writers of America Presents Ice Cold

Tales of Intrigue from the Cold War

Contributors

Edited by Jeffery Deaver

Edited by Raymond Benson

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 1, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Cold War–a terrifying time when nuclear war between the world’s two superpowers was an ever-present threat, an all-too-real possibility that could be set off at the touch of a button–provides a chilling backdrop to this collection of all-new short stories from today’s most celebrated mystery writers.

Bestselling authors Jeffery Deaver and Raymond Benson–the only American writers to be commissioned to pen official James Bond novels–have joined forces to bring us twenty masterful tales of paranoia, espionage, and psychological drama. In Joseph Finder’s “Police Report,” the seemingly cut-and-dry case of a lunatic murderer in rural Massachusetts may have roots in Soviet-controlled Armenia. In “Miss Bianca” by Sara Paretsky, a young girl befriends a mouse in a biological warfare laboratory and finds herself unwittingly caught in an espionage drama. And Deaver’s “Comrade 35” offers a unique spin on the assassination of John F. Kennedy–with a signature twist.

- On Sale

- Apr 1, 2014

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455520725

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use