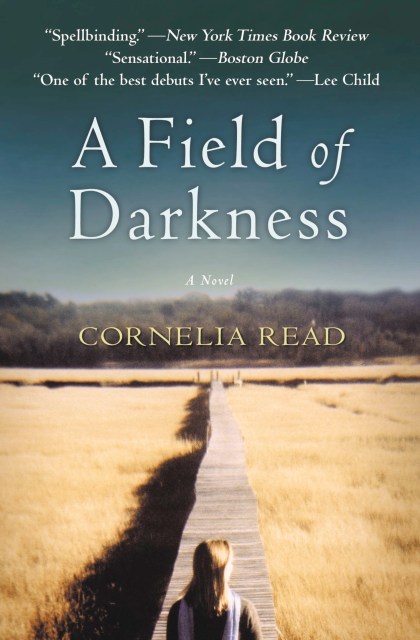

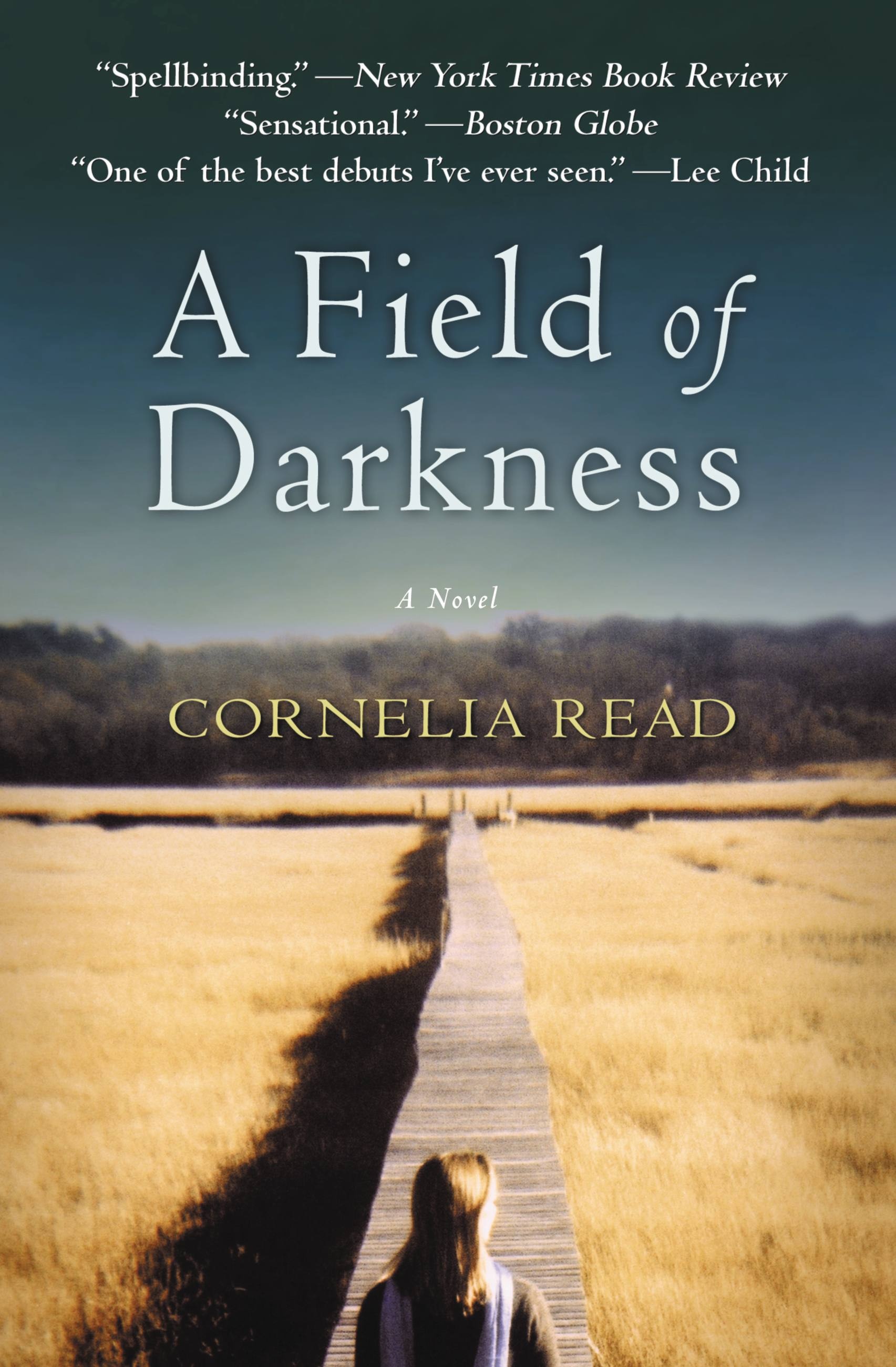

A Field of Darkness

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 11, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Madeline Dare isn’t your average detective. Born into a blue-blood family, she followed her heart to marry ruggedly handsome Dean, a farmboy-genius investor who’s as far from high society as humanly possible. Now Maddie’s stuck in the post-industrial wasteland of Syracuse, New York, while her husband spends weeks on the road perfecting the railway equipment innovation that might be their only chance to escape. She can handle churning out lightweight features for the local paper–it’s the Dean-less nights in their dingy, WASP-castoff-crammed apartment that Maddie can’t stomach. Obsession trumps angst when a set of long-buried dog tags link her favorite cousin to the scene of a vicious double homicide. Drawn by the desire to clear her cousin’s name, Maddie uncovers a startling web of intrigue and family secrets that could prove even more deadly.

Series:

- On Sale

- Jul 11, 2007

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446699495

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use