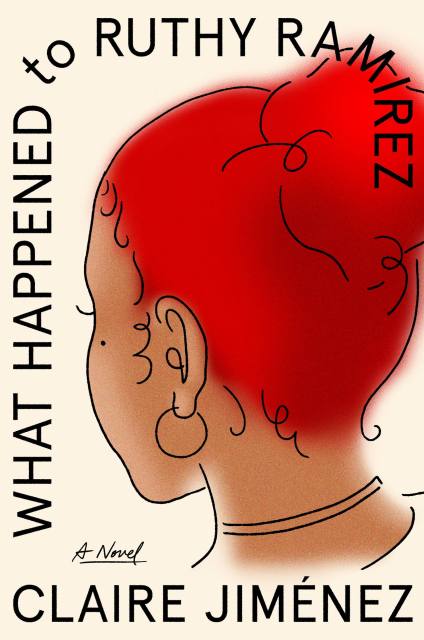

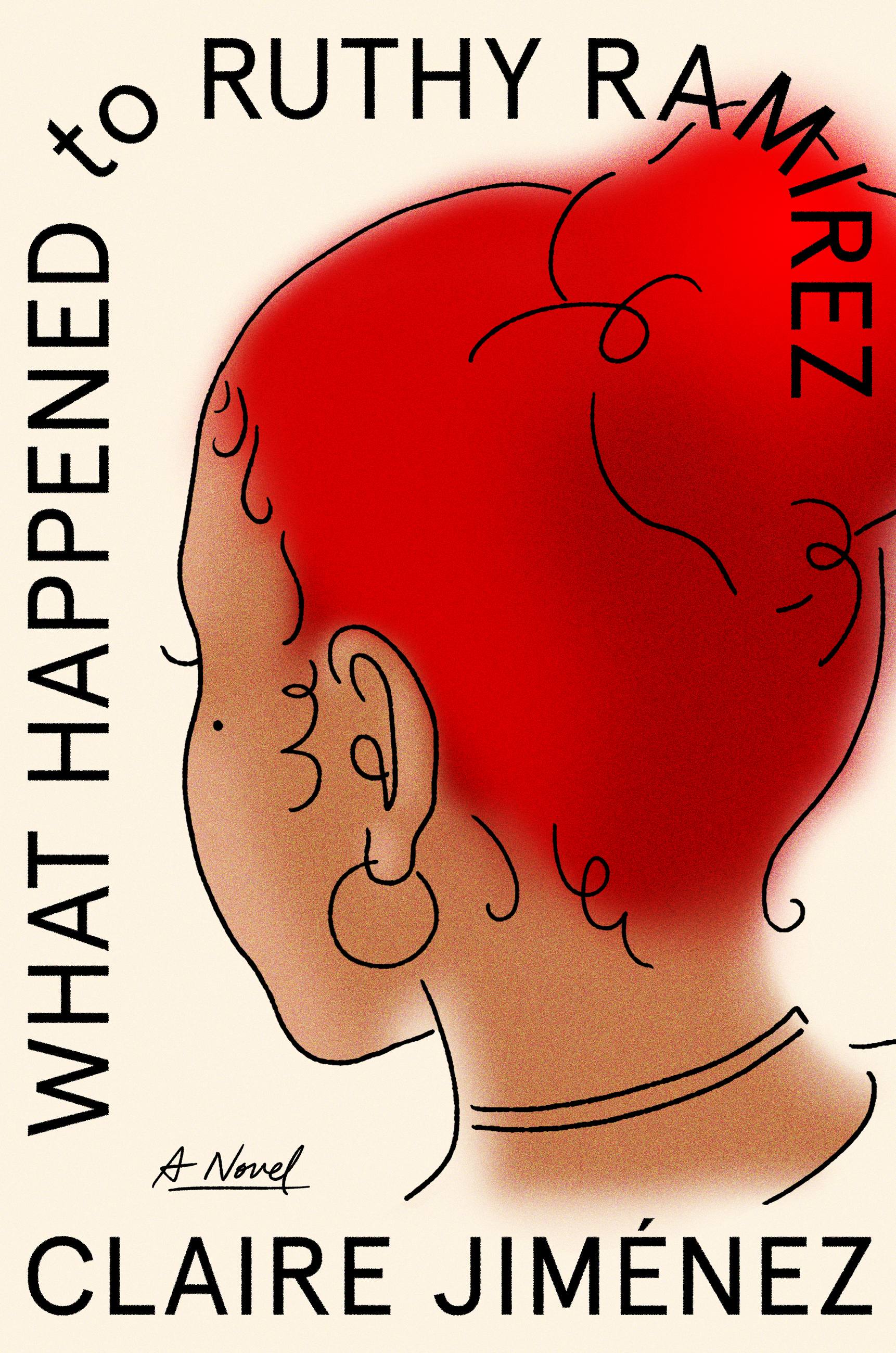

What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A powerful novel that's "hilarious, heartbreaking, and ass-kicking" (Jamie Ford) about a Puerto Rican family in Staten Island who discovers their long‑missing sister is potentially alive and cast on a reality TV show, and sets out to bring her home.

Winner of the 2024 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction · Longlisted for the Aspen Words Literary Prize · March Indie Next Pick · Belletrist, Phenomenal, Page & Pairing, and Readers Digest book club pick

The Ramirez women of Staten Island orbit around absence. When thirteen‑year‑old middle child Ruthy disappeared after track practice without a trace, it left the family scarred and scrambling. One night, twelve years later, oldest sister Jessica spots a woman on her TV screen in Catfight, a raunchy reality show. She rushes to tell her younger sister, Nina: This woman's hair is dyed red, and she calls herself Ruby, but the beauty mark under her left eye is instantly recognizable. Could it be Ruthy, after all this time?

The years since Ruthy's disappearance haven't been easy on the Ramirez family. It’s 2008, and their mother, Dolores, still struggles with the loss, Jessica juggles a newborn baby with her hospital job, and Nina, after four successful years at college, has returned home to medical school rejections and is forced to work in the mall folding tiny bedazzled thongs at the lingerie store.

After seeing maybe‑Ruthy on their screen, Jessica and Nina hatch a plan to drive to where the show is filmed in search of their long‑lost sister. When Dolores catches wind of their scheme, she insists on joining, along with her pot-stirring holy roller best friend, Irene. What follows is a family road trip and reckoning that will force the Ramirez women to finally face the past and look toward a future—with or without Ruthy in it.

What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez is a vivid family portrait, in all its shattered reality, exploring the familial bonds between women and cycles of generational violence, colonialism, race, and silence, replete with snark, resentment, tenderness, and, of course, love.

A Most Anticipated Book of 2023 by Elle • USA Today • Today.com • Ms. Magazine • Good Housekeeping • Bustle • The Week • Goodreads • Bookriot • Pop Culturely • SheReads • Litreactor • Electric Lit • The Mary Sue • People Español • Zibby Mag • Debutiful • Her Campus

Best Books of March by Shondaland • Ms. Magazine • Popsugar • Bookriot • Debutiful • Powell’s Book Blog • TIME 100 must-read book of 2023 • Booklist Top 10 debut of 2023 • Library Journal Best Pop Fiction of 2023 • The Latinidad List Best Debut Novel of 2023 • Chicago Public Library Favorite Book of 2023 • Good Housekeeping Must-Read Book of 2023 • Today.com Standout Book of 2023

Genre:

-

"A page-turner with heart, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez has it all—a haunting mystery, lovable characters, heartbreak, and hope—while also being downright hilarious. I devoured this book and look forward to whatever Claire Jiménez writes next."Ana Reyes, New York Times bestselling author of Reese’s Book Club pick The House in the Pines

-

“Jiménez unflinchingly—and sometimes hilariously—explores the complexity of family dynamics and the fierce love among mothers, sisters and daughters.”People

-

“Claire Jiménez traces how a family copes years after a devastating tragedy. The result is a moving portrait of a fractured family – and the thrilling journey they take to find out what happened to Ruthy Ramirez.”Time

-

"A rollicking, heartfelt tale of family, grief, and intergenerational healing."Elle

-

“[An] assured debut.”Vanity Fair

-

“If true crime is your guilty pleasure, you absolutely must find out what happened to Ruthy Ramirez…. Compelling…"Associated Press

-

“A funny and heartbreaking examination of sisterhood, generational trauma and the bonds that hold families together.”Today

-

“Jiménez brilliantly explores the media’s obsession with white women who go missing as opposed to women of color, the cycles of generational violence, and the beauty of a family coming together.”Shondaland

-

“There’s a delightfully subversive and maverick quality to the way first-time novelist Jiménez gives her characters the freedom to tell the truth as they see it … Jiménez brings bravery to the page, and it’s her strong storytelling and humor that make this an outstanding debut.”Kirkus (starred review)

-

"For every moment of sorrow, there are wildly comical conversations and situations between the Ramirez family, Irene, and supporting characters. Readers will likely root for the family and for Jiménez, an author to watch."Library Journal (starred review)

-

“A fantastic debut that is full of attitude, authenticity, and authority. This book is hilarious, heart-breaking, and ass-kicking at the same time."Jamie Ford, New York Times bestselling author of The Many Daughters of Afong Moy

-

"At turns desperate and witty, fresh and familiar, Jiménez’s debut taps into universal themes of familial relationships and shines a light on the lasting intergenerational effects of colonialism, violence, racism and tradition."Ms. magazine

-

"Brilliant ... This book is a knockout."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

“Sympathetic and fiery Latina characters shine in this warm and moving novel portraying a down-to-earth family with deep loyalty and longing for closure.”Booklist (starred review)

-

"Crackling with life, wit, humor, pain and personality. Readers will be tugged by the hope and despair alongside these true-to-life characters. What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez offers observations about race, class, family and the fate of missing girls beyond its title character.”Shelf Awareness

-

"Claire Jiménez's What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez is at once hilarious and heartbreaking. An original novel about mothers, daughters, and sisters, about a family broken by a profound loss. Jiménez is both storyteller and cultural critic, giving us an unflinching rejection of respectability politics, characters who love and fight, who are flawed and vulnerable and real. This book will stay with me a long time.”Jaquira Díaz, author of Ordinary Girls

-

“This novel paints a vivid family portrait and explores the familial bonds between women, colonialism and cycles of generational violence.”The Story Exchange

-

“Part mystery, part thriller, and filled with only the tender, snarky bite family can induce, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez promises to be a debut you won't want to miss.”LitReactor

-

"What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez, from the first pages, grips you like an excellent thriller and unfolds with surprising beauty. Claire Jimenez gives us religion, intergenerational trauma, reality TV, high school drama, and sisterly love. Every narrative turn and revelation provides a jolt. We're dealing with a writer deeply in touch with what us readers need. What a pleasure."Gabriel Bump, author of Everywhere You Don’t Belong

-

"I loved this book. Equal measures hilarious and haunting, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez is about a family who must keep living in the face of sudden loss. The humor makes the pages glide, but there’s true heartache at the center of this story, and I held my breath as I reached the end—full of such hope and fear for these women. Claire Jiménez is a stand out talent."Crystal Hana Kim, NBF 5 under 35 honoree of If You Leave Me

-

"The universe of Claire Jiménez’s brilliant debut novel, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez, sparkles with several generations of Puerto Rican women navigating issues of race, colonialism, gender and faith in a world cut through displacement and the quotidian challenges of day-to-day living. These memorably imagined women are imbued with a rich sense of cultural complexity, and Jiménez manages to capture a world-view rich with faith and magic, lending her work a deeply human force that is most compelling. Jiménez’s comic sense and timing are achieved with incredible skill and sensitivity."Kwame Dawes, author of UnHistory with John Kinsella

-

“Often funny, subversive, and an urgent exploration of family, grief, and womanhood, What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez reinforces Claire Jiménez as a writer for our times. With a meticulous eye that captures the occluded truths of the Ramirez women, Jiménez has written a beautiful triumph.”Xavier Navarro Aquino, author of Velorio

-

“This is a great debut novel, told from the points of view of the different characters, with some fun LOL moments, and a mystery you get engaged in, and want to learn the outcome.”Red Carpet Crash

-

"A fast-paced, engrossing mystery . . . What Happened to Ruthy Ramirez has happened to all of us, in different ways across every generation, and the magic of Jiménez’s tremendous debut is that it never stands on a righteous soapbox, yet the message is clear, down to the last word of the acknowledgments."Chapter 16

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538725962

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use