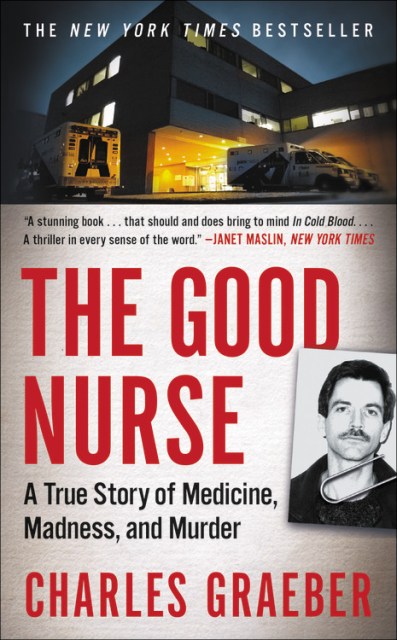

The Good Nurse

A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 30, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The mesmerizing basis of the movie starring Eddie Redmayne and Jessica Chastain—a “stunning book…that should and does bring to mind In Cold Blood”—takes you inside the mind of America's most prolific serial killer, whose 16-year long "nursing" career left as many as 400 dead. (New York Times)

Edgar Award Nomination, Mystery Writers of America

BBC (Top Ten Books of the Year)

“The best books I read this year” (top ten books, EW)

—Stephen King

“The Best Journalism of the Year.".

—The Daily Beast

“The most terrifying book published this year. It is also one of the most thoughtful…call it literary true crime…”

—Kirkus Reviews ("Best Books of the year")

After his December 2003 arrest, registered nurse Charlie Cullen was quickly dubbed "The Angel of Death" by the media. But Cullen was no mercy killer, nor was he a simple monster. He was a favorite son, a husband and beloved father, a best friend and a celebrated caregiver. Implicated in the deaths of as perhaps as many as 400 patients, he was also perhaps the most prolific serial killer in American history.

When, in March of 2006, Charles Cullen was marched from his final sentencing in an Allentown, Pennsylvania, courthouse into a waiting police van, it seemed certain that the chilling secrets of his life, career, and capture would disappear with him. Now, in a riveting piece of investigative journalism nearly ten years in the making, Charles Graeber gives us the unbelievable true story.

Based on hundreds of pages of previously unseen police records, wire-tap recordings and videotapes and interviews with whistleblowers and confidential informants, and years of exclusive jailhouse conversations with Cullen himself, the homicide detectives who worked against the clock and administrators to try and finally crack the code on Cullen’s crimes, and Cullen’s fellow nurse Amy, an overworked single mom asked to choose between protecting her friend Charlie and stopping a potential serial killer, THE GOOD NURSE weaves an urgent and terrifying tale of madness, humanity and heroism.

Cullen's murderous career in the world's most trusted profession spanned sixteen years and nine hospitals. Time and again he was fired or allowed to resign. But Cullen continued to work and kill, shielded by a hospital system that, by accident or design, successfully protected the institution while failing to protect patients. THE GOOD NURSE is a searing indictment of a crushing and dehumanizing for-profit medical system, and an inspiring human story of the previously unknown individuals who chose to risk their jobs and lives to do the right thing. Mesmerizing and irresistibly paced, this book will make you look at hospitals and the people who work in them in an entirely different way.

Edgar Award Nomination, Mystery Writers of America

BBC (Top Ten Books of the Year)

“The best books I read this year” (top ten books, EW)

—Stephen King

“The Best Journalism of the Year.".

—The Daily Beast

“The most terrifying book published this year. It is also one of the most thoughtful…call it literary true crime…”

—Kirkus Reviews ("Best Books of the year")

After his December 2003 arrest, registered nurse Charlie Cullen was quickly dubbed "The Angel of Death" by the media. But Cullen was no mercy killer, nor was he a simple monster. He was a favorite son, a husband and beloved father, a best friend and a celebrated caregiver. Implicated in the deaths of as perhaps as many as 400 patients, he was also perhaps the most prolific serial killer in American history.

When, in March of 2006, Charles Cullen was marched from his final sentencing in an Allentown, Pennsylvania, courthouse into a waiting police van, it seemed certain that the chilling secrets of his life, career, and capture would disappear with him. Now, in a riveting piece of investigative journalism nearly ten years in the making, Charles Graeber gives us the unbelievable true story.

Based on hundreds of pages of previously unseen police records, wire-tap recordings and videotapes and interviews with whistleblowers and confidential informants, and years of exclusive jailhouse conversations with Cullen himself, the homicide detectives who worked against the clock and administrators to try and finally crack the code on Cullen’s crimes, and Cullen’s fellow nurse Amy, an overworked single mom asked to choose between protecting her friend Charlie and stopping a potential serial killer, THE GOOD NURSE weaves an urgent and terrifying tale of madness, humanity and heroism.

Cullen's murderous career in the world's most trusted profession spanned sixteen years and nine hospitals. Time and again he was fired or allowed to resign. But Cullen continued to work and kill, shielded by a hospital system that, by accident or design, successfully protected the institution while failing to protect patients. THE GOOD NURSE is a searing indictment of a crushing and dehumanizing for-profit medical system, and an inspiring human story of the previously unknown individuals who chose to risk their jobs and lives to do the right thing. Mesmerizing and irresistibly paced, this book will make you look at hospitals and the people who work in them in an entirely different way.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 30, 2018

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538760970

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use