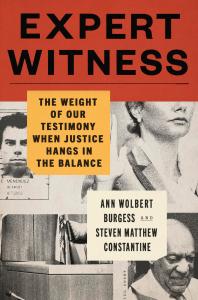

A Conversation With Ann Burgess: Forensic Nurse, Criminal Behavioral Pioneer, and Author

NS: Among other themes, EXPERT WITNESS has a strong focus on women’s empowerment. Was this intentional or did it come about naturally while writing?

AB: It emerged naturally from the work itself. When I started in the 1970s, rape victims weren’t believed, domestic violence was dismissed as a “family matter,” and male victims of sexual assault were told they couldn’t be raped. My career has been about giving voice to those who were silenced. The women’s empowerment thread runs through the book because it runs through the work — from developing the research behind rape trauma syndrome to testifying in high-profile cases like Cosby and Nassar. You can’t separate the advancement of women’s rights from the evolution of how our justice system treats victims of sexual violence.

NS: You have worked in the American legal system since the 1970s, obviously there have been numerous changes since then. What, in your opinion, has been the most positive change you’ve seen from the perspective of an expert witness, and what has been the most negative?

AB: The most positive change has been the recognition of trauma as a legitimate, measurable phenomenon that affects victim behavior. When I started, victims who didn’t fit a “type” or act “perfectly” weren’t believed. Now courts are more likely to understand delayed disclosure, fragmented memories, and seemingly contradictory behaviors as symptoms of trauma, not evidence of lying.

The most troubling development is the erosion of trust in expertise itself. We’ve gone from healthy skepticism to wholesale dismissal of expert testimony, fueled by “armchair experts” with internet connections. The Duke lacrosse case showed how quickly false narratives can override evidence, and that problem has only intensified with social media.

NS: Very early on in your career you spent a lot of time around sexual assault victims, how did you cope with such heavy and traumatizing experiences at a young age? You have recently worked on a study looking at the legal outcomes of the disappearance and murder of elder indigenous women. How has the work you did as a young woman helped shape the work you do as a seasoned professional in your field?

AB: In the 1970s, we didn’t have the language or frameworks we have now for secondary trauma. I coped by focusing on the purpose. These women trusted me with their stories, and I had an obligation to use them to prevent future victimization. That sense of responsibility became my anchor. The work with indigenous elder women connects directly to those early days because it’s the same pattern: marginalized victims whose cases are systematically overlooked. The difference is that now I have 50 years of data and credibility to demand attention for these cases.

NS: In your book you reference several specific conversations you had. Is it easy for you to recall these moments because they stood out to you so much or did you keep diaries or journals from the time that help you remember?

AB: Both. Some conversations are seared into memory — Lyle Menendez’s courtroom apology to Erik, my first interview with a rape victim who asked if she was “still a virgin.” These moments change you. But I’ve also been meticulous about documentation throughout my career. Case notes, trial transcripts, and yes, personal reflections. In this field, you learn quickly that memory alone isn’t enough. The details matter, especially when you’re testifying about them years later.

NS: You pull a lot of famous cases for EXPERT WITNESS. Did you have a hard time deciding which cases to include and which to exclude. Were there any that almost made the cut but ultimately didn’t?

AB: Absolutely. But ultimately, we chose cases that best illustrated the evolution of how society and the courts treat victims of sexual violence. Each of the book’s cases represents a broader pattern or breakthrough.

NS: What do you think that people misunderstand the most often about the work you do?

AB: That expert witnesses are “hired guns” who say whatever the side paying them wants to hear. I’ve testified for both prosecution and defense, sometimes in ways that surprised the attorneys who brought me in. My obligation is to the truth and the science, not to a particular outcome. The other misconception is that we’re emotionally detached. I feel deeply for every victim I’ve worked with. The challenge is channeling that emotion into objective, useful testimony rather than letting it cloud my judgment.

NS: For young people, especially women, interested in criminal justice, mental health, or nursing, what advice would you give them as they are just starting out in their career?

AB: Don’t wait for permission to challenge the system. When I started studying victims of rape, senior colleagues told me it would ruin my career. When I wanted to work with the FBI, I was told they didn’t need nurses. And when I began my trial work, agents told me it was a mistake. The most important advances happen when outsiders bring fresh perspectives to entrenched problems. Also, document everything. Your observations today might be the breakthrough evidence someone needs twenty years from now.

NS: In your Epilogue you talk frankly about how you struggle at times to maintain objectivity, but that you understand the big feelings you have about your cases and take steps to avoid it interfering with the integrity of your testimonies or assessments. Can you touch on how you came to be better at managing your feelings? This is something that you must have had to work on steadily throughout your career. Are there instances where you felt your emotions took a strong hold and you had to work especially hard to not let them take over?

AB: It’s been a career-long practice, and I still struggle with it. The Menendez brothers’ case was particularly challenging in that regard — understanding the depth of their abuse while watching them be dismissed as “spoiled rich kids.” I learned to compartmentalize during testimony but process afterward. I talk to colleagues, I write, I teach. Teaching especially helps because it transforms individual trauma into systemic understanding. The hardest lesson was learning that strong feelings about a case don’t compromise my objectivity. They fuel it. When you know the human cost of getting something wrong, you work harder to get it right. My passion and emotion are what got me here in the first place.

Discover the Book

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use