Film Noir Bursts Out in Full Color

It’s right there in the name: Film noir should not be in color. And yet the style of storytelling that involves both literal and metaphorical shadowy figures has often thrived in brightness, even though the most famous examples of film noir are in black and white. The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of choice for cinephiles, has curated a program called Noir in Color, featuring a range of lush, beautiful movies that tackle the conventions of film noir in full, vibrant color.

Criterion has explored variations of film noir in other programs before, and the films in the Noir in Color collection stretch the boundaries of the genre, verging into melodrama, Western, and even a bit of a musical. Yet they all feature recognizable elements of noir storytelling, from the femme fatale to the morally compromised hero to the often bleak, fatalistic worldview. Just because characters are surrounded by vivid colors doesn’t mean their souls can’t still be dark.

Perhaps the best-known noir film in the collection is the 1953 Marilyn Monroe vehicle Niagara, one of a handful of movies that allowed Monroe to explore her dramatic range. She plays a woman who conspires to kill her mentally unstable husband (Joseph Cotten) while the two are staying at a cabin overlooking Niagara Falls. Director Henry Hathaway turns the popular honeymoon destination into a forbidding, imposing landscape, contrasting its natural beauty and upbeat tourist appeal with the characters’ anguish and deceit.

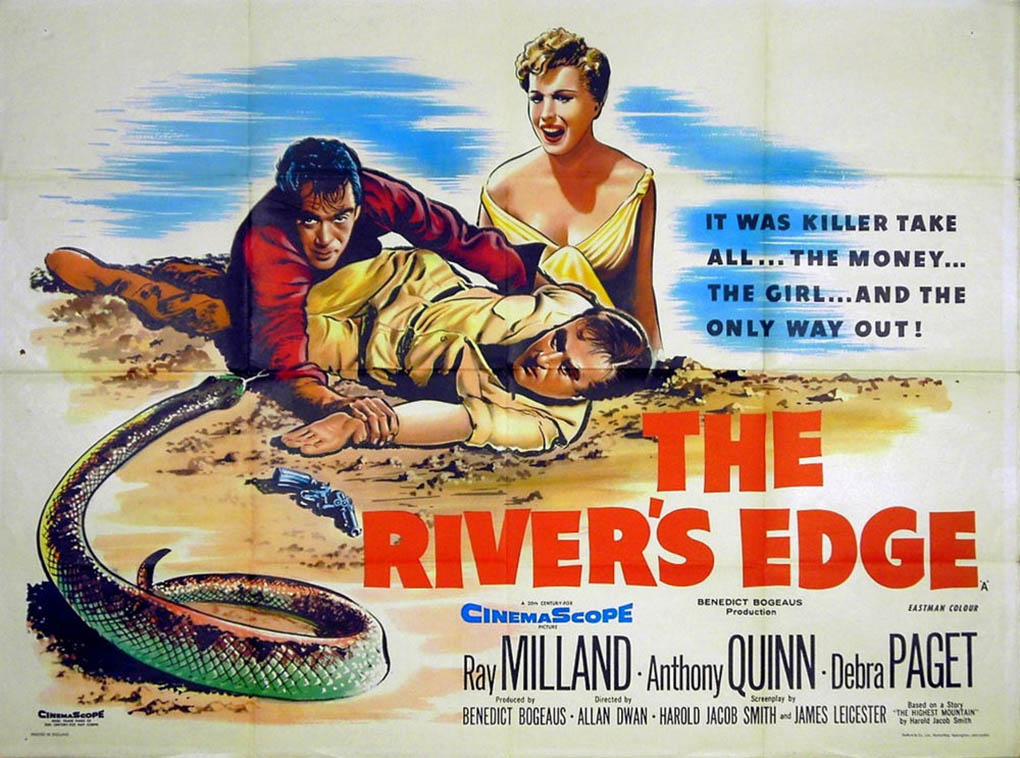

That contrast is a key element of noir movies in color, many of which are also shot in widescreen processes like CinemaScope, adding yet another visual dimension. Traditional noir movies are often cramped and confining, in addition to their chiaroscuro darkness, but movies like Gerd Oswald’s A Kiss Before Dying (1956) and Allan Dwan’s The River’s Edge (1957) take full advantage of the breadth of CinemaScope. The expansive images often have the effect of making the characters seem more stranded and adrift, as they’re dwarfed by the world around them.

In A Kiss Before Dying, based on the Ira Levin novel, Robert Wagner exudes quiet menace as sociopathic social climber Bud Corliss, who’s determined to ingratiate himself into a wealthy family, no matter what it takes. He’s casually murderous as he offs one girlfriend (Joanne Woodward) who has the audacity to get pregnant, and then moves on to dating her sister (Virginia Leith). As Woodward’s Dory teeters over the edge of a building, unaware that the man she believes she’s about to marry is preparing to push her to her death, the vast picture emphasizes just how indifferent the world is to her suffering.

Ray Milland’s Nardo Denning in The River’s Edge is nearly as unfeeling and unhinged as Bud Corliss. The pursuit of wealth is often a corrupting force in film noir, and Nardo arrives onscreen in The River’s Edge having already stolen a million dollars, eager to escape south across the border from New Mexico. He doesn’t hesitate to take out anyone who gets in his way, and his ex-girlfriend Meg (Debra Paget) realizes too late that she might be included in that group, even though Nardo tells her that he stole the money so they can be together.

Much of The River’s Edge takes place in the open desert of the American southwest, and Western elements creep into other noir movies in color as well. In 1947’s Desert Fury, based on Ramona Stewart’s novel Desert Town, a pair of criminals lay low in a small Nevada town, where wayward young woman Paula Haller (noir fixture Lizabeth Scott) has just returned home to live with her mother Fritzi (Mary Astor), a local casino owner and queenpin.

Paula and gangster Eddie Bendix (John Hodiak) fall in love, much to the frustration of upstanding local deputy Tom Hanson (Burt Lancaster) and Bendix’s partner Johnny Ryan (Wendell Corey). Paula is part femme fatale, part damsel in distress, and the isolated town could just as easily be lifted from a century earlier, with its stark conflict between outlaws and lawmen.

There’s a remarkable amount of gay subtext in the relationship between Eddie and Johnny in Desert Fury, and film noir’s ability to weave social commentary into its storylines remains fully intact in color. In 1945’s Leave Her to Heaven, based on Ben Ames Williams’ novel, Gene Tierney plays a femme so fatale that she has no need to be coy about it, openly displaying her psychotic jealousy over anyone in her husband’s life. She’s violently assertive, but for a woman in the 1940s, that may be the only way for her to take control of her own life, including terminating a pregnancy in a brutal yet never explicit scene that emphasizes the extreme acts born of desperation.

Stars like Tierney, Monroe and Scott are all the more alluring for appearing in lurid color, from Tierney’s blood-red lipstick to Monroe’s almost neon pink dress. The enticement of illicit behavior can feel more immediate and more intense in full color. It’s still film noir, just of a different shade.

Discover Noir Books

Dark City expands with new chapters and a fresh collection of restored photos that illustrate the mythic landscape of the imagination. It's a place where the men and women who created film noir often find themselves dangling from the same sinister heights as the silver-screen avatars to whom they gave life. Eddie Muller, host of Turner Classic Movies' Noir Alley, takes readers on a spellbinding trip through treacherous terrain: Hollywood in the post-World War II years, where art, politics, scandal, style—and brilliant craftsmanship—produced a new approach to moviemaking, and a new type of cultural mythology.

1940s Hollywood, murder, deception and mystery take center stage as readers reintroduce themselves to characters seen in L.A. Noire. Explore the lives of actresses desperate for the Hollywood spotlight; heroes turned defeated men; and classic Noir villains. Readers will come across not only familiar faces, but familiar cases from the game that take on a new spin to tell the tales of emotionally torn protagonists, depraved schemers and their ill-fated victims.

With original short fiction by Megan Abbott, Lawrence Block, Joe Lansdale, Joyce Carol Oates, Francine Prose, Jonathan Santlofer, Duane Swierczynski and Andrew Vachss, L.A. Noire: The Collected Stories breathes new life into a time-honored American tradition, in an exciting anthology that will appeal to fans of suspense and gamers everywhere.

From one of our finest cultural historians, The Noir Forties is a vivid reexamination of America’s postwar period, that “age of anxiety” characterized by the dissipation of victory dreams, the onset of the Red Scare, and a nascent resistance to the growing Cold War consensus.

Richard Lingeman examines a brief but momentous and crowded time, the years between VJ Day and the beginning of the Korean War, describing how we got from there to here. It evokes the social and cultural milieu of the late forties, with the vicissitudes of the New Deal Left and Popular Front culture from the end of one hot war and the beginning of the cold one—and, longer term, of a cold war that preoccupied the United States for the next fifty years. It traces the attitudes, sentiments, hopes and fears, prejudices, behavior, and collective dreams and nightmares of the times, as reflected in the media, popular culture, political movements, opinion polls, and sociological and psychological studies of mass beliefs and behavior.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next

Josh Bell is a freelance writer and movie/TV critic based in Las Vegas. He’s the former film editor of Las Vegas Weekly and the former TV comedies guide for About.com. He has written about movies, TV, and pop culture for Vulture, Polygon, CBR, Inverse, Crooked Marquee, and more. With comedian Jason Harris, he co-hosts the podcast Awesome Movie Year.