The Most Chilling Cases of Scarpetta’s Career

CHAPTER 1

I STEP OFF THE ELEVATOR on the morgue level, the air foul beneath a cloying patina of deodorizer. A stuttering fluorescent light is enough to cause vertigo, the white tile floor

blood-dripped and dirty. Cinder block walls are scuffed and smudged, the red biohazard trash cans overflowing.

It’s a few minutes past nine a.m., November first, and yesterday was the deadliest Halloween on record in Northern Virginia. People were busy killing themselves and others, the weather dangerously stormy. I left my Alexandria office late and was back before daylight. We’re far from caught up, and I’d be inside the autopsy suite right now if I hadn’t been summoned to a scene that promises to be a nightmare.

Two campers have been killed near an abandoned gold mine sixty miles southwest of here. The primitive wilderness of Buck- ingham Run isn’t a place people hike or visit, and I’ve looked up information about it, getting a better idea what to expect. Virginia’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner hasn’t had a case from there in its eighty-some-year history. That doesn’t mean there haven’t been fatalities no one knows about.

Buckingham Run isn’t mapped or accessible by motorized ground transportation, and I wouldn’t dare try it on foot. Thousands of acres are riddled with mineshafts and tunnels, among other life-threatening hazards that include contamination by poisons. There’s no telling what might live in vast forestland that’s been relatively untouched by humans since before the American Civil War.

It goes without saying there are large wild animals, perhaps some that people wouldn’t imagine, and I’m not talking about only bears. Images flash nonstop from videos that Pete Marino has been sending since he arrived at the scene. The nude female body impaled by hiking poles floating in a lake reflecting fall colors. The campsite scattered near the entrance of the abandoned gold mine, danger and go away barely legible on centuries-old warning signs.

Marino filmed with his phone while shining a light down a mineshaft, illuminating a body caught in collapsed wooden scaffolding, the bloody face staring up blindly. I can hear Marino’s booted feet moving through loose rocks and grit. I see his light painting over rusty iron rails . . . An ore cart shrouded in spiderwebs . . . Then he’s exclaiming “Holy shit,” the light stopping on a bare footprint that seems to have been left by a giant . . .

Leaving the building. I send a text to Marino’s satellite phone. A former homicide detective I’ve worked with most of my career, he’s my forensic operations specialist. Several hours ago, he was airlifted to the scene with Secret Service investigators. Marino is getting an overview before I show up and is excited by the find of a lifetime, as he puts it. I’m not sharing his positive sentiments about evidence that’s sensational and likely fake. Any way I look at it, we could have a real mess on our hands.

If you want me to bring anything else tell me now. Typing with my thumbs, I push through the ladies’ room door.

I feel for the wall switch, turning on the light inside a closet-size space with a sink, a toilet and a plastic chair with uneven legs. By now I’m programmed not to pass up a chance to use the facilities. In the early days I might have been the only female except for maybe the victim. At death scenes I don’t get to borrow the bathroom, and where I’m going doesn’t have one.

While I’m washing up with institutional soap, my computer-assisted smart ring alerts me that Marino is answering my texts to him. Drying my hands with cheap paper towels, I unlock my phone.

Bring bolt cutters, he’s written back, and I’ve already thought of it.

All set. Anything else? I answer.

A snakebite kit. Don’t have.

There’s one in my truck.

They don’t work, I reply, and we’ve been through this countless times since I’ve known him.

Better than nothing. They’re not.

What if someone gets bit? He adds the emoji of a coiled snake. I answer with the emojis of a helicopter and a hospital before tucking my phone in a pocket. Reapplying lip balm, I brush on mineral sunblock, spritzing myself but good with insect repellent. I pick up my Kevlar briefcase, a birthday gift from my Secret Service agent niece, Lucy Farinelli. Looping the strap over my shoulder, I’m confronted by my reflection in the mirror.

It’s as bad as I expected after days of little sleep, eating on the run and too much coffee. When Lucy notified me about the two victims inside Buckingham Run, she said to dress for extreme conditions. The tactical cargo pants and shirt, the boots I’m wearing wouldn’t be flattering on most women. I’m no exception. I text Lucy that I’ll meet her outside. First, I need to chat with Henry Addams, I tell her, and she’ll understand why.

The funeral director is on his way here to pick up a body from an unrelated case, an alleged suicide from yesterday. I texted him that we need to talk when he gets here. He doesn’t know what’s happened inside Buckingham Run. Nothing has been on the news yet. But he’ll realize something is going on or I wouldn’t have communicated that I’m waiting for him.

As I follow the corridor, observation windows on either side offer remnants of recent horrors. Air-drying in the evidence room are the bloody clown costumes donned by two ex-cons who picked the wrong home to invade last night. The Bozos (as they’re being called) got a trick rather than a treat when they were greeted with a shotgun.

Sneakers with laces tied in double bows were left in the road at the scene of a pedestrian hit-and-run. A shattered wristwatch shows that time stopped at nine p.m. for the victim of an armed robbery in a retirement home parking lot. The paper strip from a fortune cookie reads, Your luck is about to change, and it did when a woman fell off her deer stand.

Inside the CT room’s scanner, images on monitors are of a fractured skull. The decomp autopsy room’s door is closed, the red light illuminated. Inside is the badly decomposed body of a possible drowning in the Potomac River, the victim last seen fishing almost a week ago.

I’m walking past a supply closet when Fabian Etienne emerges from it. He’s holding a box of exam gloves as if he just happened to be in the area, and I know his ploys.

* * *

“Hey! Doctor Scarpetta!” Fabian’s voice interrupts my grim preoccupations. “Wait up!” Flashing me one of his big smiles, he’s been watching the cameras, waiting for me to head out of the building.

Fabian intends to have another go at me in hopes I might change my mind, and I understand his frustration. I also am keenly aware that he craves drama and is easily bored and underutilized, as he puts it. When he was growing up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, he was earning money giving swamp tours by the time he could drive a car.

His father is a coroner, and Fabian grew up in a deadly environment, he often quips. He’s not afraid of much, and there’s no type of case he wouldn’t handle given the opportunity. But he can’t be involved with Buckingham Run for a lot of reasons. The Secret Service wouldn’t allow Fabian at the scene, and I’m not to discuss the details with him or anyone unauthorized. More to the point, I need him here.

“I’ve helped Lucy haul everything out to the chopper, and she let me look inside the cockpit.” His Louisiana accent is more New York than Southern. “OMG, that thing is sick. She says it can go more than two hundred miles an hour. And mini–machine guns can be swivel-mounted. Plus, it can see through fog. You sure I can’t come with you, Doctor Scarpetta? I promise I’ll be helpful.”

His straight black hair would be halfway down his back were it not pinned up under a surgical cap, black with a skull pattern. Black scrubs show off his goth tattoos and a lean body that’s whippet strong and fast. People find him sexy. Dreamy is what my secretary, Shannon, says, describing him as a combination of Cher and Harry Styles.

“I’ve never been in a chopper, certainly nothing like that thing in our parking lot. It’s smoking hot and straight out of The Avengers,” Fabian says excitedly. “If you bring me with you, I know you won’t regret it.”

“I’m not running the investigation or calling the shots.” I repeat what I’ve told him several times now.

“You’re in charge of the bodies,” he says. “Seems like you could have anyone help that you decide.”

“Access to the scene is extremely restricted for safety and other reasons. The priority should be that you help where most needed,” I reply with patience I’m not feeling. “We’re short-staffed and overwhelmed by cases, Fabian. That’s the biggest reason why you’re staying here. I can’t have you and Marino at the scene with me . . .”

“So much for on-the-job training,” Fabian says. When he gives me one of his wounded looks, I feel like a bad mentor, and that’s his intention.

“I’m sorry you’re disappointed.” I find myself apologizing to him often these days, because he doesn’t take no for an answer. I don’t like being put in the position of denying him what he wants and inevitably sparking a drama. My forensic psychologist husband says that subconsciously Fabian sets me up to be the idealized and overly involved mother who’s the root of his troubles. We have a parent-child relationship with oedipal overtones, according to Benton. All I know is Fabian can be a holy terror when he doesn’t get his way.

“It’s important I have some idea of what to expect,” he’s saying. “Everything’s so hush-hush, like something really bizarre is going on. I asked Lucy a few very basic questions and she wouldn’t say anything except two people are dead inside Buckingham Run. And obviously, the Secret Service has taken over the investigation. That right there tells me plenty. Whatever’s going on must be a really big deal.”

“There’s not much known yet and it’s unwise to speculate.” I won’t get into this with him. “I need you to look after things here during Marino’s and my absence. The semi-trailer needs deconning and setting up. I know the Secret Service is in charge and will be bringing in special equipment. We have to abide by their protocols. And everything must be ready for us when we return with the bodies.”

“Why does he get to be there instead of me?” Fabian says, and I hope the day comes when he and Marino get along.

After Lucy located the victims, her first call after me wasn’t going to be Fabian. She’s known Marino most of her life. Lucy told him to meet her at the Secret Service hangar outside of Washington, D.C., in southern Maryland. From there Lucy flew him to the scene as the sun was coming up. He’s my boots on the ground until I arrive, and in Fabian’s mind that was like winning the lottery.

“I’m the one who needs the experience.” He continues making his argument in the corridor. “Marino grabs all the good cases, leaving me to take care of chicken shit that doesn’t teach me anything new.”

“Gathering the proper equipment and supplies for a complicated scene isn’t chicken shit,” I reply. “If I get there and don’t have what we need, it could be catastrophic.”

“As my mom keeps reminding me, this isn’t what I signed up for.” Fabian is fond of making quote marks in the air. “I’m supposed to be an investigator, not a grip or a gofer.” More air quotes. “Doctor Reddy pretty much gave me free rein, which is why I took the job to begin with. Not that I’m sorry he’s gone. But I don’t get to do half of what I used to.”

I didn’t hire Fabian. My predecessor, the former chief medical examiner, did, and that’s unfortunate. Elvin Reddy ran the Virginia M.E. system into the ground and would do the same to me given the opportunity. We worked together briefly when both of us were getting started and have an unpleasant history. At first, I couldn’t be sure about Fabian or anybody else working here.

Loyalty hasn’t been a given, and it’s been tricky knowing who to trust. But I don’t want to be unfair. Innocent until proven guilty is the way it’s supposed to work, and I can’t afford for Fabian to quit. We’re down to three death investigators, including Marino. The other one is part-time on the way to retired. As much as Fabian may get on my nerves now and then, I know he’s talented. I feel a responsibility toward him and a certain fondness.

“I have plenty that you can help me with as long as you abide by my instructions,” I reply. “There are always investigations that need following up on.”

“That’s what I want to do.” His mood is instantly brighter. “Finding out the important details that tell the story is my special sauce. That’s why I was such a damn good P.A.,” he adds modestly about his start as a physician’s assistant. “I’d find out details from the patients that the docs would never imagine. Stuff that was a game changer in terms of a diagnosis. Like my dad’s always saying, the big thing is listening . . .” Air quotes again.

“We’ll have to finish talking about this later, Fabian . . .”

“You know, hear what someone’s saying to you and pay attention. But you know how rare that is . . . ?”

“I certainly do, and I’ve got to go.”

I can see on a wall-mounted video monitor that Henry Addams has pulled up to our security gate. He’ll be driving into the vehicle bay any minute.

“Addams Family is here to pick up Nan Romero, the suspected suicide from yesterday morning.” I indicate what’s on the monitor.

“I’ll take care of it.” Fabian is in much better spirits. “By the way, that’s a weird one. I don’t know what Doctor Schlaefer’s said to you.”

“We’ve not had a spare moment to talk,” I answer.

“The painter’s tape bothers me,” Fabian volunteers as he walks with me. “I can’t imagine anyone wrapping their lower face like that. Especially a woman.”

“I expect Investigator Fruge to be calling with further information,” I reply. “I’m sure she knows we’ll be pending the cause and manner of death until we get the toxicology results.”

Fabian heads back toward the elevator as I continue along the corridor. It begins and ends like a morbid conundrum, the receiving area the first and last stop in my sad medical clinic. No appointments are required, our services free to the public. Death doesn’t care who you are, everybody treated equally. With rare exception the only thing our patients have in common is they never thought they’d be here.

When bodies arrive, they’re rolled in through a pedestrian door and weighed on the floor scale. They’re measured with an old-style measuring rod and assigned case numbers before waiting their turn inside the refrigerator. Names are hand- written in what I call the Book of the Dead, the large black logbook chained to the chipped Formica shelf outside the security office window.

On the other side of the bulletproof glass Wyatt Earle’s khaki uniform jacket is draped over the back of his chair. The remains of takeout food are on his desk, and propped in a corner is the aluminum baseball bat he borrows from the anatomical division where bodies donated to science are stored and eventually cremated.

We have no choice but to pulverize large pieces of bones; otherwise they won’t fit inside the cremains boxes returned to loved ones. Wyatt carries the bat while making his rounds after hours. Unlike me, he’s more afraid of the dead than the living.

Two mauled bodies in the woods. Top secret autopsies. The most chilling cases of Scarpetta’s career.

In this thrilling new installment of Patricia Cornwell’s #1 bestselling Scarpetta series, chief medical examiner Dr. Kay Scarpetta finds herself in a Northern Virginia wilderness examining the remains of two campers wanted by federal law enforcement.

The victims have been savaged beyond recognition, and other evidence is terrifying and baffling, including a larger-than-life footprint.

After one of the most frightening body retrievals of her career, Scarpetta must discover who would commit murders this savage, and why.

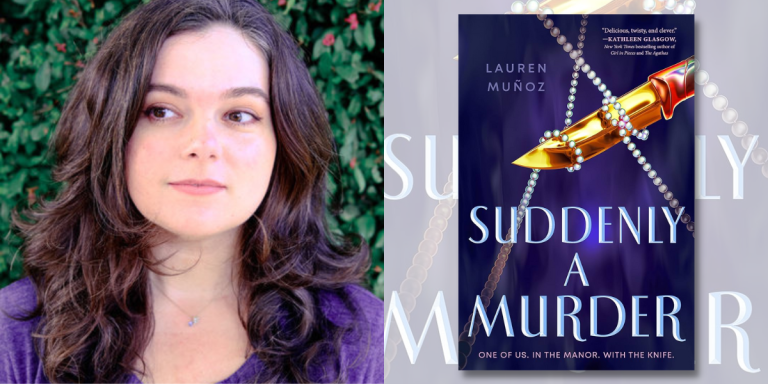

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use