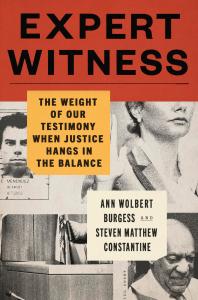

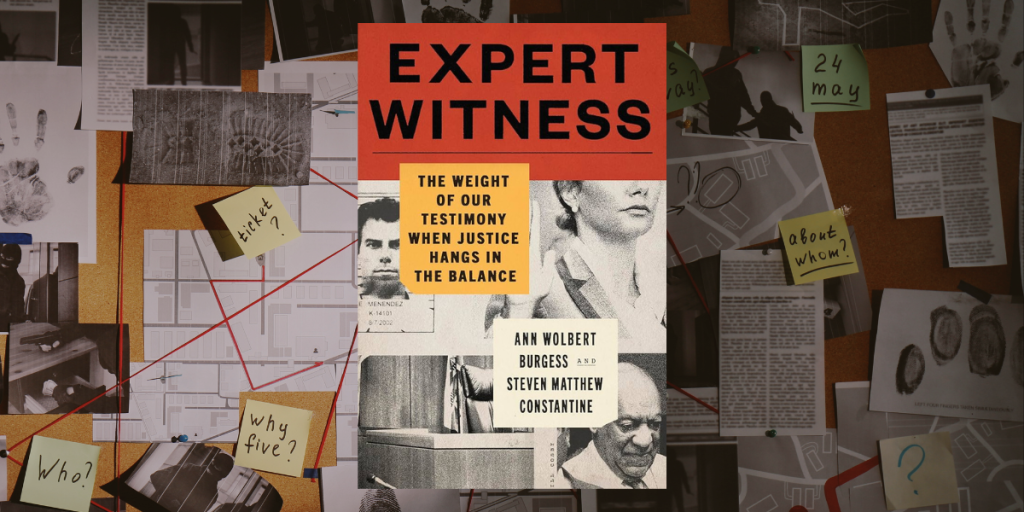

Read the Excerpt: Expert Witness by Ann Burgess

Introduction:

The Rise of the Expert Witness

There’s nothing more absolute than a courtroom. It’s the biggest stage for the biggest cases with the highest stakes. Sometimes it’s a matter of life or death. Sometimes it’s the prospect of a multi‑billion‑ dollar payout for victims of corporate malpractice. And sometimes its meaning goes far beyond anything money can touch, like remorse, dignity, repentance, and the terrible burden of being put on display for the entire world to see. But whatever the circumstances, the purpose of a trial always comes down to the same two things: truth and justice. It’s as simple as that.

Vincit omnia veritas.

The truth conquers all things.

As an expert witness, I’ve learned to hold that phrase as a personal mantra. It helps me block out distractions and focus on my one singular goal: to stand before a jury of twelve people and explain, in precise, calm clarity, why a certain gunshot pattern means what it means, or how the neurobiology of trauma can cause a witness to remember the exact geometric pattern of subway tiles but not the face of the man who raped her. I’ve done this as a court‑ recognized expert on mental illness, rape, violence, post traumatic stress disorder, crime classification, profiling, the neurobiology of trauma, elder abuse, infant and child abduction, and countless other specialized topics. I’ve testified as an expert on nationally televised cases that millions of people tuned in for, and I’ve worked behind closed doors on cases no one’s ever heard about. I’ve helped legal teams devise strategy. I’ve squared off against lawyers chomping at the bit to undermine my credibility. I’ve seen the faces of victims contort into something far beyond grief. And through it all, I’ve learned to hold pain at arm’s length. Not because I don’t feel it—I do, acutely—but because to rise to that witness stand with my integrity intact, I must set aside my own feelings, my personal politics, my instincts to comfort or to rage. I must remember my job. Because, ultimately, the jury, those twelve ordinary people plucked from their lives, are the ones who hold the potential to shift the course of someone’s entire existence. My task is to focus solely on what I can control, to speak the truth to the best of my ability.

It’s a complicated thing, being an expert witness. Courtrooms are hostile places where words become swords. Despite the specific nature of each case and the individuals involved, it’s rarely just individuals who are on trial. Instead, trials tend to be about something messier, something more amorphous, more manipulable— like memory, or trauma, or the way prevailing cultural expectations can either illuminate or completely distort the reality of events.

And so that’s the challenge. Every time I walk into that courtroom, I pass rows and rows of scuffed benches and nervous relatives, I hear the click, click, click of the stenographer’s keys, and make my way to the witness box, right next to the judge. From the second I enter the arena, I know that every syllable, every hesitation, every minor adjustment of my glasses or papers or pen is being analyzed, assessed, and turned into narrative by not just the lawyers, but the jurors who are equally caught up in their own problem outside of these walls: sick kids, ailing parents, overdue bills, job stress. Regardless of the nature of the case, it’s often pretty difficult to keep their attention for the entire time of your testimony, let alone the full trial. If you get too technical, their eyes glaze over with boredom; and if you dumb your responses down too much, you risk annoying them or losing your credibility altogether.

Most of the time, these citizen juries are comprised of people who want to be anywhere but in that courtroom. And so my job, then, is to do something fundamentally paradoxical: to be impartial but persuasive, to be authoritative but unassuming. To be precise, to be authentic, and to earn the jury’s trust, case after case testimony after testimony, without theatrics or lawyerly bravado but with the steadiness of truth.

Why?

Because truth matters. Justice matters.

I do this work because somewhere, someone’s entire life might hinge on whether I explain something well enough for a jury to truly understand.

And I can’t afford to screw up, or second‑ guess myself, when there’s so much at stake.

_______________________________

Though not always explicitly labeled as such, expert witnesses have been a cornerstone of Western law since the beginning of the criminal justice system. Records from as far back as the classical period, in ancient Athens, describe physicians summoned to speak about broken bones and the intricate nature of wounds in front of the courts. In the Roman era, courts sought out midwives to explain childbirth, scribes to scrutinize handwriting, and surveyors to resolve boundaries of land. And so it continued, in various iterations across various civilizations, up until 1554, when an English judge described the value of such a specialist in the context of a legal proceeding:

If matters arise in our law which concern other sciences or faculties, we commonly apply for the aid of that science or faculty which it concerns. Which is an honourable and commendable thing in our law. For thereby it appears that we do not despise all other sciences but our own, but we approve of them and encourage them as things worthy of commendation . . . In an appeal of mayhem the Judges of our law used to be informed by surgeons whether it be mayhem or not, because their knowledge and skill can best discern it.

It’s pretty intuitive, really. If issues arise in a trial that can best be addressed by an expert in any given field, then bring in that expert. Especially if the case hinges on confusing or disputed information where the courts lack sufficient context to make informed decisions on their own.

Adhering to basic logic, then, property cases typically brought in surveyors, tax cases brought in bookkeepers, and on and on for different kinds of specialists and tradesmen of direct empirical knowledge, year after year after year. The catch, however, was that this system only worked when experts were neutrally appointed by the court to speak impartially for both sides of the case. Once judges began allowing opposing sides to choose and pay for their own expert witnesses—toward the end of the eighteenth century— the entire premise of impartial experts collapsed. With money came allegiance. And with allegiance came the slow unraveling of objectivity. Who qualified as an expert and to what standards should their expert testimony adhere? No one could say for sure— and that was a big problem.

Simultaneously, there was a massive society‑ sized shift at the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Science was emerging as a driving factor of economic growth— and consequently, the sudden professionalization of the field meant that courts now faced an equally emergent need for scientific experts to parse the growing complexities of modern disputes.

This was a defining moment, a reimagination of what an expert witness could be. Before, expertise had been tethered to the empirical— a surveyor’s lines were clear, an accountant’s numbers held true. Now? Expertise was abstract, dealing with theory and the complexities of experiments. A judge could follow a map, but what was he to make of thermodynamics? A jury might comprehend the contours of land, but how could they be expected to make sense of the dense, contradictory tides of scientific testimony? And to make matters worse, even opposing experts tended to disagree, causing courtrooms to become battlegrounds of opposing scientific theories and leading to questions about the validity of science in general. Rising through the turmoil, a popular joke captured public sentiment of the time: “There are three kinds of liars— the common liar, the damned liar, and the scientific expert.”

This simmering tension came to a head in the case of Folkes v. Chadd (1782), which concerned the deterioration of the harbor in the town of Wells, in northern England, a once‑thriving port now rendered useless and inaccessible to ships. Desperate to protect their livelihoods, town residents invested in two artificial sluices that were designed to scour the harbor and keep it operational. However, the sluices failed. And so, looking for somewhere to place the blame, the harbor’s board of commissions took legal action against a local landowner, Sir Martin Browne Folkes, alleging that his artificial embankment had disrupted the natural flow of water and, in doing so, choked the harbor.

The question posed to a jury in August 1781 was twofold: Had Folkes’s embankment damaged the harbor? And, if so, did that damage warrant its removal? To exactly no one’s surprise, the prosecution’s opening‑ day playbook involved a cast of traditional experts— ship captains, mariners, and other men whose expertise was based on empirical observations directly attributable to their training and experience— who were paraded right up to the witness stand, one after the next after the next. One by one, they took the stand, each solemnly affirming that, yes, they had witnessed the harbor’s rapid decline firsthand; and that, yes, the harbor’s deterioration could be directly attributed to the construction of Folkes’s embankment.

To great surprise, however, the landlord’s lawyers didn’t combat the prosecution with an army of their own traditional experts. Instead, on the second day of the two‑ day trial, the landlord’s lawyers presented a single expert: Robert Mylne, a Fellow of the Royal Society and a famed London‑ based engineer. Mylne used his time on the stand to explain how the silting of the harbor was due to unseen forces, time’s slow erosion, and the confluence of six estuary rivers depositing vast quantities of silt along Norfolk’s north coast for years upon years. He then assured the jury that the prosecution’s experts weren’t lying with their testimony but that they’d simply mistaken correlation for causation, confusing proximity with proof. The truth, Mylne concluded, did not always reveal itself to the naked eye. It required theory. It required science. And, crucially, it required experts who could see beyond the visible and into the hidden mechanisms of nature itself.

To the outrage of Wells’s townsfolk, the jury sided with Folkes based on Mylne’s persuasive testimony. The harbor’s board was in disbelief. In their eyes, Mylne was an outsider who knew nothing about the situation, compared to the intimate knowledge of locals whose entire lives had been shaped by the rhythms of the harbor. Using this as their rationale, the commissioners’ lawyers pushed for a new trial “on the ground that the defendants were surprised by the doctrine and reasoning of Mr. Mylne,” adding that Mylne’s explanations were too theoretical and shouldn’t have been permitted in the first place.

Authorities agreed that the commissioners deserved an opportunity to counter Mylne’s testimony with expert testimony of their own, stating: “In matters of science, the reasonings of men of science can only be answered by men of science.” With that, a new trial was set for the following summer. However, in an attempt to avoid any additional controversy, the judges added a caveat that both parties should pre‑ exchange, in writing, the opinions of the experts whom they intended to rely on in court “so that both sides might be prepared to answer them.” The judges further added, somewhat presciently, an observation that the case “has influenced the whole county of Norfolk, and perhaps the whole country may be affected by it.”

As the date for a second trial was set, the harbor commissioners swiftly assembled a team of four well‑known experts of scientific rank and regard, whose specialties ranged from engineering to cartography to river navigation and water drainage. Folkes, for his part, hired one additional expert: John Smeaton, a man whose accolade‑heavy résumé signaled him as the foremost authority on harbors in all of England. Both sides visited the harbor and conducted research to inform their reports. Both sides then exchanged their findings— first with one another and then with the jury, as directed— and set off to prepare for court. Battle lines had been drawn in the sand.

But something curious happened when the retrial began on July 25, 1782. Though the very premise of the retrial hinged on the commissioners’ desire to counter Mylne’s scientific testimony with a scientific expert of their own, the exact opposite happened. None of the commission’s four specifically hired experts were given a chance to testify. Instead, the commission’s attorney once again summoned ship captains and mariners to speak about their personal experience of the harbor’s deterioration. And when they were finished, the attorney contended that no scientific experts, especially Smeaton, should be allowed to address the court, since such testimony would concern the hidden laws of nature and “was matter of opinion, which could be no foundation for the verdict of the jury, which was to be built entirely on facts, and not on opinions.”

All of this back‑ and‑ forth speaks to the uncertainty surrounding expert testimony at the time. There was no precedent. No guidelines. Just a vacuum where rules should have been, left to be filled by those with the loudest voices or the most persuasive rhetoric. Bias seeped into the cracks, distorting the fragile balance of justice.

This was exactly what happened in the wake of the commission attorney’s request to ban scientific experts. The presiding judge, Henry Gould, chief justice of the Royal Court of Common Pleas, accepted the argument that Smeaton’s evidence “could be no foundation for the verdict of the jury”— given its hypothetical basis on natural process that would take years to measure, test, or otherwise verify as true. The jury, unsurprisingly, sided with the harbor commission. Equally nonsurprising, Folkes’s lawyers refused to let the matter rest. They immediately appealed for a third trial, citing their star witness’s improper exclusion. And so it went, back and forth, back and forth— no clear resolution, only the slow grind of bureaucracy, the law stumbling in circles, never quite finding its way.

However, what happened next was a series of events that would become the origin story for the rise of partisan expert testimony in the modern legal system. Where Justice Gould viewed Smeaton’s testimony as too speculative for trial, the justice in charge of the third trial, Lord Mansfield, chief justice of the King’s Bench, strongly believed that the country’s foremost harbor expert should be given the opportunity to speak.

“The question is, to what has this decay been owing?” Mansfield began. “The defendant says, to this bank. Why? Because it prevents the back‑ water. That is matter of opinion:— the whole case is a question of opinion . . . I cannot believe that where the question is, whether a defect arises from a natural or an artificial cause, the opinions of men of science are not to be received.”

To Lord Mansfield, if the proposed witness was known as an expert on the matter at hand, his opinion should be considered proper evidence. Lord Mansfield’s decision marked a transformative moment in the legal landscape. By rejecting the distinction between the expert and his expertise, Mansfield set a standard for the admissibility of scientific matters of opinion. In maintaining that it was not for the court to qualify the expert’s opinion, Mansfield’s ruling shaped the nineteenth‑ century practice of expert testimony altogether. If a person was qualified as an expert, his or her expert opinion would be permitted into the courtroom; it was the job of the cross‑ examiner to expose the weaknesses of the testimony and for the jury to weigh it. Or, as Professor James Thayer of Harvard Law School went on to describe it: Up until Mansfield’s decision, “experts were thought of in the old way, as being helpers of the court . . . But at last the modern conception came in, which regards the expert as testifying, like other witnesses, directly to the jury.”

With Smeaton finally allowed to provide his expert testimony, Folkes’s team won a decisive victory, one that significantly expanded the scope and standard of experts in courtrooms across the country. And before long, the impact rippled outward, beyond England, beyond the eighteenth century, until it reached American courts, where the role of the expert witness would continue to grow, shaping trials in ways Lord Mansfield himself could scarcely have imagined.