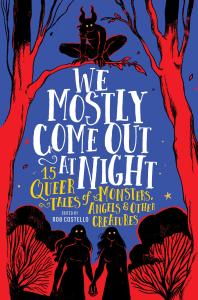

What We Have in Common with Monsters: An Interview with Rob Costello

We sat down with author and editor Rob Costello to discuss his new short story collection We Mostly Come Out At Night, a new bundle of cross-genre YA fantasy stories about what it really means to be a monster. Buckle up as we hear from Rob about what drew him to monsters, his editing process, and his upcoming novel.

NS: We Mostly Come Out At Night inverts traditional fairytales and folklore by placing monsters not as othered, predatory creatures but rather as heroic and complex as a form of queer reclamation. Why do you think the concept of “monster” is such a natural jumping off point for writing about queer lives?

RC: The sad fact of the matter is that queer and trans folks have an awful lot in common with monsters when it comes to how we get treated in our cisgendered, heteronormative world. The LGBTQIA2S+ community has long been demonized by reactionary elements in society as somehow unfit and dangerous, especially where children are concerned. We all know the slurs: groomer, deviant, predator. It’s no coincidence that in the run up to the Presidential Election, the extreme right-wing in this country has focused so much energy on queer book bans and oppressing trans rights. We are the easy scapegoats and convenient boogeymen they use to mobilize their base and consolidate power.

Put simply, they have cast us as their monsters.

But the funny thing about monsters is that they exist purely in the eye of the beholder. (After all, even the Xenomorph Queen in Aliens was somebody’s mom.) The very qualities about queer and trans people that seem to frighten the bigots so much also happen to be the exact same things that we know make us special, beautiful, compassionate, and strong. All you need to do to see the truth is to look with better eyes.

There’s something empowering about reclaiming the monster label from those who would weaponize it against us. It’s an act of defiance. An act of pride. And that’s what We Mostly Come Out at Night is all about. My fourteen talented contributors and I wanted to offer young queer and trans readers a book that would inspire them to view themselves with the best possible eyes.

NS: Walk us through the process of editing a short-story collection. How do you balance the different narrative styles and voices? What’s your editorial approach?

The first thing I should emphasize about the editing process on We Mostly Come Out at Night is that it was very much a collaboration. Not just with each author, but also with my brilliant editor at Running Press Kids, Britny Perilli, who was a wonderful partner and had a major hand in shaping the book. I feel tremendously lucky!

For me, the key to striking the right balance was all about finding the right mix of contributors from the beginning. So a lot of planning and research went into assembling my invitation shortlist. I knew that while the book was going to be about monsters, I didn’t want it to be a straightforward horror anthology, but rather something broader that featured a variety of voices, tones, and styles representing the full breadth of speculative fiction. Sure, I wanted scary stories. But I also wanted stories filled with romance and wonder, laughter and pathos, queer rage and queer joy. Of course, representation matters, too, and so it was essential that the Table of Contents reflect the rich diversity of our audience of young readers. It was also important to me to include exciting new voices along with well-established bestsellers and award-winners.

Once the writers were on board, I encouraged them to interpret the theme however they wished. The only rules were that every story had to include a monster of some sort and that each one needed to center on empowering queer themes and subject matter appropriate for a YA audience. Since I didn’t want to end up with (for example) ten vampire stories, there was also a lot of conversation about the specific monster(s) each contributor planned to write about. Some folks chose to create their own original creatures. Many put new spins on popular favorites, while a few others tapped into the unique monster lore of their own cultural heritage. Overall, I think it worked out pretty well. Ironically, we didn’t end up with any vampires whatsoever, and while angels, aliens, and werebeasts all appear more than once in the book, they’re so different from story to story I think most readers won’t even notice.

Ultimately, my primary editorial goal with We Mostly Come Out at Night was to ensure that every reader who picks up a copy finds at least one story to love. If nothing else, I hope we’ve succeeded in that!

NS: With We Mostly Come Out at Night, you not only work as an author, but also as an editor. What was the editorial process like in comparison to writing? How has it informed your own writing process?

RC: What’s surprised me most about working as an editor on We Mostly Come Out at Night is just how much I’ve truly loved every minute of it.

As a writer, there’s always some wounded, fragile, defensive piece of my ego wrapped up in every project I write. This makes it hard to fully enjoy the experience of publishing my work. As a writer, I struggle to suppress the voices of doubt, that internal critic, my chronic imposter syndrome. As a writer, the work is never quite good enough, never quite finished, never quite what I envisioned when I first set out to write it.

The upshot for me has been to alleviate much of the burden from my tender writerly ego. While I wouldn’t say that my own story was an afterthought (quite the contrary, in fact: it’s one of my favorite pieces I’ve written), I am far less concerned with how readers respond to it than I am with what they think of the book as a whole. I do peek at our Goodreads reviews (I know I shouldn’t, but alas, I can’t help myself), and I am truly just as delighted when a reader calls out a story they love that isn’t mine. All around, it’s felt like a far more generous and healthy way to work.

This is the gift that editing has given to me as a writer. I think every writer should try editing something if the opportunity presents itself, if for no other reason than to get out of your own head for a while and focus your creative energy on uplifting the work of others. I hope I have the chance to this again. In fact, I would make a career out of it if I could. It’s been that much fun!

NS: You’re coming out with your first novel in 2025. Can you tell us a bit about that. How do you feel your work in short fiction has prepared you for long-form writing?

RC: Thank you so much for asking about my novel! It’s called An Ugly World for Beautiful Boys (Lethe Press, April 2025), and as a gritty, contemporary coming-of-age novel, it’s a pretty big departure from the speculative monster stories of We Mostly Come Out at Night. It’s set primarily in a fictional Adirondack town in the summer of 2016, and revolves around a queer teen named Toby Ryerson who, in a fit of rage, outs the closeted bully he’s been secretly hooking up with. This sets off a chain of events that lands the bully in the hospital, torpedos Toby’s relationship with the overprotective older brother who raised him, and leads him to the perilous underbelly of the New York City club scene where disaster awaits. It’s a book about the burden of secrets and coping with a legacy of shame, and while I’m sure that all sounds pretty bleak, Toby’s story is often quite funny and hopeful and portrays the unbreakable bonds of love that exist within even the most dysfunctional of families. It’s the novel of my heart, and I’m so happy and proud that readers will soon be able to discover it.

I think the most important thing that short fiction has taught me as a novelist is the absolute necessity of understanding what it is that I’m trying to say. For me, writing a novel is a slow, iterative process of self-discovery. I rarely know when I begin exactly where it’s headed. Figuring that out requires intensive focus and a lot of revision, cutting the flab while honing and shaping the text down to the essential core of the story itself. This is a skillset I’ve developed over many years of writing and publishing short fiction. To be successful, short stories demand a clarity of thought and execution that I think longer forms can sometimes obscure. There’s nowhere to hide in a short story. Every word counts. Every sentence needs to earn its place by contributing to the overall impact of the piece as a whole. But to do that successfully means first understanding on an almost molecular level just exactly what effect you want the story to achieve.

With a 5000 word story it’s pretty straightforward to figure that out. Less so with an 80,000 word novel that deals with multiple characters, themes, and ideas. Nevertheless, the necessity of self-discovery remains the same. It’s not until I finally know what I’m trying to say that I can get out of my own way to say it!

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use