Murder as a Comfort in Mysteries

I wrote my first novel—my first murder mystery—during a family crisis. Three years ago, my mom was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. I quit my job to support her through treatment. In the long hours when she was sleeping or getting poison pumped into her body, I needed something to do. I found myself turning to a life-long passion: writing. In college, I’d been a slam poet. As an adult, I’d shifted to blogging and nonfiction writing. At 40, I decided to try my hand at fiction for the first time.

Writing Mother-Daughter Murder Night was a creative distraction and escape from the terror of my mom’s cancer journey. I shared the draft with my mom as I wrote, and it helped us get through dark days.

But why write about murder? Why didn’t I write poetry again, or something lighter? Why write about violence and death while facing a crisis of mortality?

On one level, I was writing what I knew. I’ve always been a fan of murder mysteries, as has my mother. But I think the real reason I chose to write a detective story is deeper than that.

One of the craft books I found at the library was Barbara Norville’s Writing the Modern Mystery (1986). In it, Norville compares the modern detective story to the medieval morality play. The criminal transgresses—whether against laws of man or God—and the detective metes out justice. Many of the golden age detectives operate as superheroes of rationality in a world that can often feel irrational.

I was looking for craft tips, so I mostly skimmed Norville’s philosophical musings about the meaning of murder mysteries. But her ideas stuck with me. The more I wrote, the more I noticed I was doing what those golden age detectives did. I was trying to bring order and logic into a world that had become arbitrary and terrifying.

I spent my days with my mom in hospitals, at the mercy of busy doctors and broken machines. We had very little power or control over our days. But when I was writing, I was in control. It felt comforting to imagine an amateur detective who could follow the clues and find the answer. It felt powerful to set her to righting the wrongs done.

At a fundamental level, I wrote a murder mystery to beat death. To contain it, pin it to the page, and make it answer for its petty threats.

This is why detective stories are so comforting. They start with a violent, irrational act—a rent in the social fabric. But then, the hero methodically stitches up the tear. Maybe she does it with logic. Maybe she does it with a bumbling sidekick (or, in my story, with her estranged daughter and granddaughter). However the detective proceeds, we the readers, experience the satisfaction of seeing her put the just, rational world back together. It’s fun to see how the detective does it, to solve the puzzle alongside them. But the part that satisfies, the part that comforts: that is the repair. The healing. The fiction that all that was broken can be made whole again.

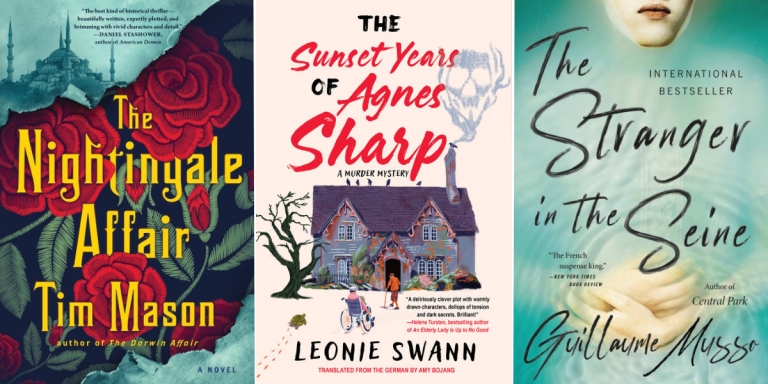

Discover the Book

A High-powered businesswoman Lana Rubicon has a lot to be proud of: her keen intelligence, impeccable taste, and the L.A. real estate empire she’s built. But when she finds herself trapped 300 miles north of the city, convalescing in a sleepy coastal town with her adult daughter Beth and teenage granddaughter Jack, Lana is stuck counting otters instead of square footage—and hoping that boredom won’t kill her before the cancer does.

Then Jack—tiny in stature but fiercely independent—happens upon a dead body while kayaking. She quickly becomes a suspect in the homicide investigation, and the Rubicon women are thrown into chaos. Beth thinks Lana should focus on recovery, but Lana has a better idea. She’ll pull on her wig, find the true murderer, protect her family, and prove she still has power.With Jack and Beth’s help, Lana uncovers a web of lies, family vendettas, and land disputes lurking beneath the surface of a community populated by folksy conservationists and wealthy ranchers. But as their amateur snooping advances into ever-more dangerous territory, the headstrong Rubicon women must learn to do the one thing they’ve always resisted: depend on each other.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use