Bad Guys Have More Fun: An Analysis of Villains in Mystery Novels

Every Holmes must have his Moriarty, so it is (probably) said.

Every Holmes must have his Moriarty, so it is (probably) said.

A mystery novel must inevitably have a crime. In order for there to be a crime, someone must have done something wrong. The detective is trying to figure out what has happened, and at the same time, someone is trying to prevent the detective from figuring out what has happened.

A good mystery novel is a tug of war: a back-and-forth between the person who is trying to solve the crime, and the person who has committed the crime and may be planning others. Without this tug of war, there really isn’t a mystery. You may not even have a story.

Granted, sometimes the moral lines become a bit blurry. The antagonist, technically the “bad guy”, may appear to be justified in what they have done. They may be acting in defiance of an unfair law: one of the laws that the detective may be tasked with upholding. Or this person may not be an evil person by nature. The villain may not even be human at all, but rather a force of nature: a violent storm, or an outbreak of a deadly illness. But for the purposes of this essay, we’ll take a look at the decidedly human villains.

Types of villains

The criminal mastermind

Moriarty falls into this category, along with the villains in most major comic book series. This villain is a gleeful puppet master, manipulating time and evidence to send the detective in the wrong direction, and causing untold pain, misery, and grief for all of the victims and their families. This person may have an army of sidekicks and henchmen (or women, or people in general) to do their dirty work, and the mastermind sits back and eagerly plans the next caper. (Cue the maniacal laughter.)

The quiet one

“He seemed like such a nice man.” “She wouldn’t have hurt a fly.” Quotes like these have appeared in countless news stories over the centuries, as friends and neighbors react in disbelief to news that their mild-mannered neighbor may be a ruthless serial killer. This person flies under the authorities’ radar for much of the book, either staying in the background, or politely offering their help as a concerned citizen. In more than one cozy mystery, the murderer turns out to be someone’s meek and mild assistant who’s just about had enough. There may be substantial overlap between “the quiet one” and one of the other types of villains, such as cold-blooded cruel person or self-proclaimed moral arbiter.

Cold-blooded cruelty

This villain is in the same category as the criminal mastermind, though perhaps without the same level of dramatic panache or Mensa-level plotting. You see this kind of villain in thrillers about serial murders. This killer may inflict specific kinds of cruelty on the victims, and may arrange the bodies in certain manners for when they are found by the police. Or the villain may end up killing/victimizing several people over the course of the story, for no motive other than fulfilling the villain’s ultimate goal: staying on the run from authorities, covering up a primary murder or a theft, and so on. This person sees most of their victims as pawns in a long-running chess game: disposable pieces to be sacrificed on the road to checkmate.

The cruelty is especially powerful if it’s inflicted by someone whom the protagonist trusted: a family member, a romantic partner, or a trusted friend or co-worker.

Abuse of power, or self-proclaimed moral arbiter

This person may be in a position of authority, such as a police officer, judge, or member of the clergy. They may use their position as the means to carry out a crime. Or, they may be a person with a rigid, hypocritical code of ethics, and they see it as their duty to target people they see as sinful or immoral. Historical mysteries seem to be quite fond of villains who are self-proclaimed moral arbiters or abusers of power, perhaps as a way to point to unjust social conditions or ways of thinking that were common at the time. (The reader will likely read this and smugly think, “Oh, how far we’ve come, we’re so enlightened in our present day,” or reflect “We’re still dealing with these problems today. We’re not superior after all.”)

In it for the money

Financial gain is a motive for many a murder. But there are many variations on this. The villain could be a hired killer with no personal animus toward the victim, but they were hired to do their job and they have to do it. Or, as we have seen in countless whodunits, the villain wants to kill off their wealthy older relative/parent figure so they can inherit the fortune. (If the wealthy person is already dead, the villain will go after whoever is next in line to inherit.)

The sympathetic villain

This person killed someone or otherwise committed a crime, and yet the reader can’t help but have sympathy for them. This is especially true if the victim of the crime was an unlikable (or downright evil) person, or if the perpetrator was rebelling against an unjust law or social condition. (But in that case, the perpetrator runs the risk of becoming the self-proclaimed moral arbiter, as described above.) The line may be blurred if it turns out the killer committed the murder in self-defense, but then did questionable things to cover it up.

The tropes

“We’re not so different after all.”

Sometimes, the detective and the perpetrator may come face to face. The perpetrator casually remarks that in a lot of ways, the two of them are opposite sides of the same coin. And this might get the reader thinking. The detective may kill people over the course of their work, but it’s expected that the detective is (mostly) justified in what they do. The villain may have skills that could have been used for the good of the world, but those skills are being used for evil.

Holmes and Moriarty are both exceptionally smart people. But due to circumstances, they are on opposite sides of the law. Neil Gaiman switched the two around with the Lovecraft-influenced fantasy horror story “A Study in Emerald,” in which Moriarty was the renowned detective investigating a murder (with Sebastian Moran acting as his Watson), and the perpetrator is, so the reader is invited to believe, Holmes under an alias.

The reading of the will

There is something about the reading of a rich old person’s will that turns their seemingly nice, loving relatives and devoted servants into cold-blooded killers. It’s a favorite plot device in countless whodunit plays, books, and video games. The old person announces that they’ve made their will, this is who is in the will, and this is how they will inherit. So it should not be a surprise when people start turning up dead shortly thereafter. Therefore, if any rich older people in the process of making their wills should read this, keep the terms of the will between yourself and your lawyer. Don’t tell your relatives in advance of your death.

The victim was the true villain

Quite a few Agatha Christie novels have a murder victim who wasn’t exactly likable in life. Either they may have been merely irritable, domineering, or downright rude, or they may have done something terrible to someone else. Linnet Ridgeway, the victim in Death on the Nile, is perceived as having stolen the fiance of her ex-best friend Jacqueline de Bellefort. (The movie adaptations run the gamut from making Linnet looking remorseful and trying to make amends to showing her as being a downright b—.) On the more extreme end of the scale, consider Murder on the Orient Express. Samuel Ratchet (ne Cassetti), known to be an unsavory person in life, was revealed after his death to have been an absolute monster. Therefore, in the mind of the reader, the killer (or killers) acted justifiably.

The Villain Origin Story

In a lot of books and movies, we don’t see many villains who are in the game of villainy for the sheer pleasure of it. Something made them who they are. The villain may have had an unhappy childhood, in which they were abandoned and/or abused by their parents or guardians. Or maybe they were the shy, awkward kid who got teased all the time at school. (This isn’t to say, however, that the popular, outgoing, socially adjusted kids can’t become villains either; you see plenty of those as well.) Or maybe the villain was rejected by a former spouse or romantic partner, and they are still not over it.

Best villains

This is not a perfectly scientific list; we recognize that one person’s dynamic, fiendish villain may be another reader’s wet blanket.

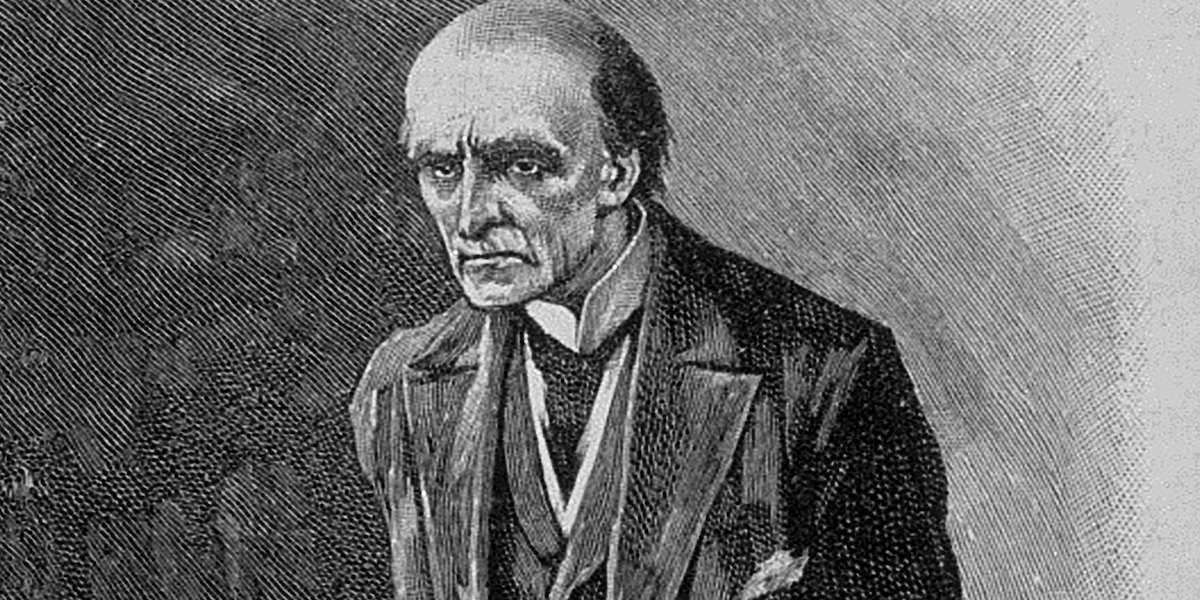

Professor James Moriarty

The Napoleon of Crime, as Holmes calls him. He is the most devious of criminals that Holmes has come up with in his extensive career, and the most impossible to bring to justice; indeed, at one point, Holmes remarks to Watson that if you could say anything bad about Moriarty, he could game the system and successfully sue you for slander or libel. Moriarty’s only major appearance in the Holmes stories is “The Adventure of the Final Problem.” The story is notorious for its ending, in which Holmes and Moriarty seem to plunge together to their deaths over the Reichenbach Falls. (Conan Doyle brought Holmes back in a subsequent short story after much public outcry, but Moriarty has not been seen since.)

Mrs. Danvers

The sinister housekeeper Mrs. Danvers made psychological manipulation, gaslighting, and mind games into a high art form in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. From the moment the new Mrs. de Winter sets foot inside Manderley, Mrs. Danvers makes it very clear that she feels the newcomer is nowhere near the same league as her late mistress. She wears the new Mrs. de Winter down, a little at a time, in a series of passive-aggressive actions and statements. In one rather terrifying moment, Mrs. Danvers nearly induces Mrs. de Winter to jump out of a high window to her death.

Jame “Buffalo Bill” Gumb

Most discussions of Silence of the Lambs, either the original 1988 novel by Thomas Harris or the blockbuster 1991 film starring Anthony Hopkins and Jodie Foster, tend to put the sinister, cannibalistic Dr. Hannibal Lecter at center stage. But the main villain in the story is the twisted serial killer Jame Gumb, known to the police and the public as “Buffalo Bill.” He abducts women, tortures and kills them, and removes the skin from their bodies.

Arnold Zeck

As Holmes has Moriarty, New York-based gentleman detective Nero Wolfe has Arnold Zeck: a cunning, clever master criminal who seems to be involved in every kind of organized crime in the city. Zeck periodically phones Wolfe to warn him against investigating certain cases, with certain dire consequences if he does. Zeck is also not above sending his henchmen to fire guns into the greenhouse containing Wolfe’s beloved orchids. And yet, in spite of all this, Wolfe and Zeck seem to have a mutual admiration for each other’s skills and intelligence.

Amy Elliott Dunne

Amy Elliott, one of the two (very unreliable) narrators of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, was her wealthy parents’ miracle child, and the inspiration for their Amazing Amy book series, but the real-life Amy resented living in the perfect fictional Amy’s shadow. She is clever and resourceful, but also cold, calculating, and heartless. As an adult, Amy grows increasingly discontented with married life with her husband Nick Dunne, and she decides to fake her own disappearance and death so that Nick will be arrested and charged with her murder. She is even willing to get back in touch with an ex-boyfriend, murder him, and make up a story about having been kidnapped and raped in order to keep up her deceptions.

Stephen Norton

The villain of Agatha Christie’s final Hercule Poirot novel, Curtain, the seemingly meek and mild-mannered Stephen Norton is, in reality, a cruel, calculating puppet master. He manipulates every one around him into committing terrible acts, including murder, and is able to give himself a perfect alibi. He caused a woman to be arrested and convicted for a murder of which she was completely innocent (and of which Norton was guilty). Over the course of the book, Norton plots several other murders by proxy, including against Poirot’s old friend Captain Hastings and his family. Poirot, by that time in poor physical health from old age, must take drastic measures to stop Norton once and for all.

Count Fosco

Sir Percival Glyde is dangerous, abusive, and thoroughly unlikeable in Wilkie Collins’s The Women in White, but it is the clever and sophisticated Count Fosco who is really pulling the strings and masterminding the action. Several characters note that the young heiress Laura Fairlie (Glyde’s new wife) bears a striking resemblance to Anne Catherick: the haunted, childlike, and gravely ill “woman in white.” But it is Fosco who comes up with a fiendish idea: to shut Laura away in an asylum under Anne’s name, and to have Anne, when she dies, buried under Laura’s name.

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What to Read Next

Erin Roll is a freelance writer, editor, and proofreader. Her favorite genres to read are mystery, science fiction, and fantasy, and her TBR pile is likely to be visible on Google Maps. Before becoming an editor, Erin worked as a journalist and photographer, and she has won far too many awards from the New Jersey Press Association. Erin lives at the top floor of a haunted house in Montclair, NJ. She enjoys reading (of course), writing, hiking, kayaking, music, and video games.