Promotion

Use MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

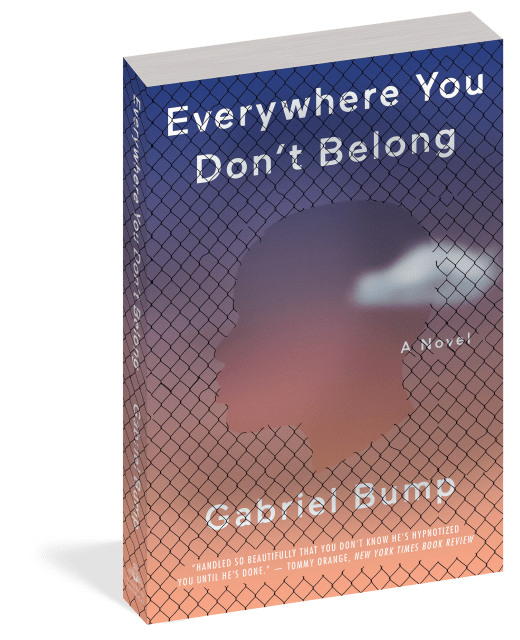

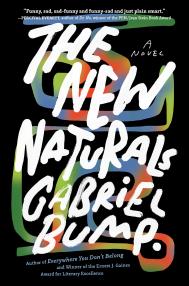

Everywhere You Don't Belong

Contributors

By Gabriel Bump

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.95Price

$22.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 12, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A New York Times Book Review Notable Book of 2020

Winner of the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence

“A comically dark coming-of-age story about growing up on the South Side of Chicago, but it’s also social commentary at its finest, woven seamlessly into the work . . . Bump’s meditation on belonging and not belonging, where or with whom, how love is a way home no matter where you are, is handled so beautifully that you don’t know he’s hypnotized you until he’s done.” —Tommy Orange, The New York Times Book Review

In this alternately witty and heartbreaking debut novel, Gabriel Bump gives us an unforgettable protagonist, Claude McKay Love. Claude isn’t dangerous or brilliant—he’s an average kid coping with abandonment, violence, riots, failed love, and societal pressures as he steers his way past the signposts of youth: childhood friendships, basketball tryouts, first love, first heartbreak, picking a college, moving away from home.

Claude just wants a place where he can fit. As a young black man born on the South Side of Chicago, he is raised by his civil rights–era grandmother, who tries to shape him into a principled actor for change; yet when riots consume his neighborhood, he hesitates to take sides, unwilling to let race define his life. He decides to escape Chicago for another place, to go to college, to find a new identity, to leave the pressure cooker of his hometown behind. But as he discovers, he cannot; there is no safe haven for a young black man in this time and place called America.

Percolating with fierceness and originality, attuned to the ironies inherent in our twenty-first-century landscape, Everywhere You Don’t Belong marks the arrival of a brilliant young talent.

Winner of the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence

“A comically dark coming-of-age story about growing up on the South Side of Chicago, but it’s also social commentary at its finest, woven seamlessly into the work . . . Bump’s meditation on belonging and not belonging, where or with whom, how love is a way home no matter where you are, is handled so beautifully that you don’t know he’s hypnotized you until he’s done.” —Tommy Orange, The New York Times Book Review

In this alternately witty and heartbreaking debut novel, Gabriel Bump gives us an unforgettable protagonist, Claude McKay Love. Claude isn’t dangerous or brilliant—he’s an average kid coping with abandonment, violence, riots, failed love, and societal pressures as he steers his way past the signposts of youth: childhood friendships, basketball tryouts, first love, first heartbreak, picking a college, moving away from home.

Claude just wants a place where he can fit. As a young black man born on the South Side of Chicago, he is raised by his civil rights–era grandmother, who tries to shape him into a principled actor for change; yet when riots consume his neighborhood, he hesitates to take sides, unwilling to let race define his life. He decides to escape Chicago for another place, to go to college, to find a new identity, to leave the pressure cooker of his hometown behind. But as he discovers, he cannot; there is no safe haven for a young black man in this time and place called America.

Percolating with fierceness and originality, attuned to the ironies inherent in our twenty-first-century landscape, Everywhere You Don’t Belong marks the arrival of a brilliant young talent.

Genre:

-

Winner of the 2020 Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence

Winner of the 2021 Great Lakes Colleges Association (GLCA) New Writers Award for Fiction

Winner of the 2020 Heartland Booksellers Award for Fiction

Winner of the 2021 Black Caucus of the American Library Association's First Novelist Award

A BuzzFeed Most-Anticipated Book of the Year

A Electric Lit Favorite Novel of 2020

A Chicago Public Library Best of the Best Books of 2020

“A comically dark coming-of-age story about growing up on the South Side of Chicago, but it’s also social commentary at its finest, woven seamlessly into the work . . . Bump’s meditation on belonging and not belonging, where or with whom, how love is a way home no matter where you are, is handled so beautifully that you don’t know he’s hypnotized you until he’s done.”

—Tommy Orange, The New York Times Book Review

“A witty coming-of-age tale . . . Bump’s first book manages to be both crazy funny—and deadly serious.”

—People

“This book is astonishing. You'll be smiling even as your heart is breaking, and you'll tip willingly into this world Bump offers you because what appears again and again are spectacular beams of light, also called love, also called hope, also called family. Gabriel Bump has established himself as a stunning talent to be reckoned with.”

—Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King

“Briskly paced . . . Bump makes his novel debut with hilarious yet ruthless insight. He mixes his observations of the systemic racism and cycle of unrest with the ridiculousness of and unrelenting affection for human nature. There is no time for hand-wringing or self-pity, but even amidst the injustice and fight for survival, there's time for human contact and love.”

—Salon.com

“Classic bildungsroman, made better by a lot of love for warts-and-all Chicago, and I see dashes of Percival Everett in Bump’s deadpan, how his characters cross the stage with a sashay (and sometimes more). Welcome, Claude! We’re glad you’re here.”

—The Paris Review Daily (Staff Pick)

“A charming wit infuses Bump’s debut novel . . . Bump’s coming-of-age narrative is propelled by wonderful vignettes with uncannily real dialogue marked by his beguiling humor and insight.”

—The National Book Review

“[A] pointedly affecting debut novel . . . With deft writing and rat-a-tat, laugh-until-you-gasp-at-the-implications dialog, Bump delivers a singular sense of growing up black that will resonate with readers.”

—Library Journal (starred review)

"[An] astute and touching debut . . . Bump balances his heavy subject matter with a healthy dose of humor, but the highlight is Claude, a complex, fully developed protagonist who anchors everything. Readers will be moved in following his path to young adulthood."

—Publishers Weekly

“A sharply funny debut novel that introduces an irreverent comic voice . . . By telling it in short vignettes rather than a traditional narrative, he creates striking images and memorable dialogue that vibrate with the life of Chicago's South Side . . . genuinely hilarious.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Everywhere You Don’t Belong is an excellent coming-of-age novel that will make you laugh when you least expect it.”

—Shelf Awareness

“Bump’s first novel is a clipped and penetrating look at adolescent hope in the face of powerful social forces.”

—Booklist

“[A] spiraling coming-of-age tale about abandonment and perseverance . . . sparks with originality . . . The ripped from the headlines plot of Everywhere You Don’t Belong draws instant interest.”

—Foreword Reviews

“In Everywhere You Don’t Belong, Gabriel Bump completely, beautifully, and energetically illuminates the heretofore unrecognized lines connecting Ellison's Invisible Man to Johnson's Jesus’ Son. This is a startling, original, and hilarious book. I look forward to reading it again.”

—Adam Levin, author of The Instructions

“Sometimes you open a book and you know from the very first page, this thing's alive. You know what I mean? (How often does this not happen? You open a book and it’s just a book?) Gabriel Bump's Everywhere You Don't Belong’s got a racing pulse, and a beautiful propulsion, a ton of humor, wonderful dialogue, deep characterization, and cold-eyed-truth.”

—Peter Orner, author of Maggie Brown and Others

“A brilliant and harrowing debut.”

—Noy Holland, author of Bird

"Some works you read them and you sense that you will never quite engage life as you did before. Bump is a storyteller at the top of his game, testifying through characters we love and hate, with dialogue so lean, mean and ready, it's explosive. Everywhere You Don’t Belong is a literary blues, raw and rowdy and big and brawling, yet smooth and polished and crafty, a novel that a city like Chicago deserves. Gabriel has achieved here that special confluence of the writer, the craft, and the moment that makes art we cannot afford to ignore, especially at this moment.”

—Arthur Flowers, author of Another Good Loving Blues and I See the Promised Land

“One solace for living in dark times is they conjure singular new artists like Gabriel Bump whose visions may shepherd us into the light. Everywhere You Don't Belong is a startlingly powerful novel, an unusual concentration of opposing forces—blind rage vs. empathy, comedy vs. tragedy, despair vs. hope—that resists every label it evokes: picaresque, bildungsroman, generational family saga, political novel, comic novel, love story. It’s all of those things at once and much more—an instant American classic for the post-Ferguson/Trump era.”

—Jeff Parker, author of Ovenman

- On Sale

- Jan 12, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781643750859

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use